Rynear Tyson’s family lived in Kaldenkirchen in the Rhineland of Germany in the 1600’s, after the end of the Thirty Years War. At that time the established churches were protected by the local government, while the Quakers and Mennonites were persecuted. Rynear’s father Theiss was a shopkeeper, like Theiss’ father Peter. At some point Theiss became a Mennonite and was harassed because of it. In 1655 he was fined 100 gold guilders for refusing to pay a tax, and his goods were confiscated. The family was threatened with banishment from Kaldenkirchen. Theiss joined the Reformed Church, possibly to deflect further persecution. It seems to have worked, because the Reformed pastor appealed to the Duke, who allowed them to stay and ordered that their goods be returned and the fine remitted. Some of their children would take the religious dissent one step further and become Quakers.

Quaker missionaries had visited the Rhineland on multiple visits starting in 1657. William Ames, Steven Crisp, Roger Longworth, Benjamin Furley, and William Penn himself—they had traveled through the region, visiting nobles and townspeople, spreading the creed of the Quakers.1 The most receptive to the message were the Mennonites, so the missionaries focused on towns where Mennonites already lived.

Those who supported the Quakers faced additional persecution. At the Synod of Julich the pastor from Kaldenkirchen, Pastor Eylert, complained that he had not been able to “restore to their senses” the women of the town who had become Quakers; he thought they were bewitched.2 When Quaker missionary Elizabeth Hendrick visited in 1680 with two companions, they were only able to meet with those who were already Quakers; the other townspeople called them evil names and threw dirt at them. As Elizabeth’s husband wrote, “Ye Calvinist priest stood by and countenanced it, there are both papists and Calvinists in that place; and ye papist have proclaimed it from theire pulpits that none was to Entertaine or take into their houses any quaker….”3

By 1680 there were Quakers in Krefeld. They held regular meeting for worship, and in 1681 they held a wedding.4 Derrick Isaacs op den Graeff and Nolcken Vijten had declared their intentions of marriage, and in 3rd month 1681 they married each other. The certificate was signed by nineteen witnesses, nearly all of the members of the Friends’ Meeting.5 Almost all of the signers would emigrate to Pennsylvania just a few years later.

Theiss and Neesen had eleven known children, six of whom emigrated to Pennsylvania.6 They were close-knit, acting as sponsors for the baptisms of each others’ children, and selling land to each other.

In June of 1683 a group of Quakers, including Rynear and four of his sisters and their husbands, assembled in Krefeld on the first stage of a journey to Pennsylvania. They traveled up the Rhine to Rotterdam, then to London, where passage had been booked for them to Pennsylvania. The arrangements were made by letters back and forth between Benjamin Furley and James Claypoole, two wealthy Quaker merchants, one of Amsterdam, and one of London. Claypoole intended to sail with his own family on the same ship.7 The Krefeld Friends were delayed between Rotterdam and London, and Claypoole was quite anxious about their arrival. There would be a penalty of £500 if they did not arrive to pay their passage and sail by the 6th of July. As Claypoole wrote to Benjamin Furly, “He [the Captain] is not to stay beyond the day for one person, but to sail if with 60. So now I having engaged by thy order I desire thee not to fail, but send me the money, and let the friends get here in good time to take up their goods and ship them again, and buy such necessaries as they want, which will take up 6 or 8 days time. So before the last day of this month [June] they ought to be here.”8 They still had not arrived by July 3rd and Claypoole was “fain to loiter and keep the ship at Blackwall upon one pretense of another, for when she comes to Gravesend the owners will not suffer her to stay many days. And indeed it would trouble me very much to go away without them, besides the great loss it will be to them, for the master will abate nothing of the ½ freight.” They had still not arrived by the 10th, but eventually they did show up and the Concord began its voyage across the Atlantic.

The Concord, under Captain Jeffries, weighed over 500 tons and could carry 26 cannon, 40 sailors, and 180 passengers, although there were fewer on the October 1683 voyage. The passengers brought butter, cheese, clothing, iron, tools, rope, fishnets, and guns. Claypoole wrote that the voyage was comfortable and that no one died on board. In fact two babies were born at sea.9 They were within sight of England for the first three weeks, then 49 days out at sea, about average for the time.10 They successfully avoided the three main perils—storms, contagious illness on board, attack by Barbary pirates—and landed in Philadelphia in early October.11

When they landed in Philadelphia, ferried on shore in small boats, they found a few houses and many trees. Francis Daniel Pastorius had arrived a few months earlier. He reported that the city “consisted of three or four little cottages; all the residue being only weeds, underwood, timber, and trees.”12 He got lost several times just a few blocks from his house. The “house” was probably just a dug-out cellar. The settlers began to build their houses by digging out a hole for the basement. They were sometimes forced to live in this shelter through the first winter until they could finish erecting the rest of the house above His “cave” was at the present-day Front and Lombard Streets.13 Pastorius wrote that he built a house there with an inscription. “A little house, but a friend to the good: keep away, ye profane.” The Krefeld Quakers met there and drew lots for their tracts where they were to settle—their little territory of Germantown, six miles north of the center of the town.14 It was unusual for Penn to allow settlers to choose their own land. The usual procedure, as specified in his warrants to the Surveyor General, left the location to the discretion of the surveyor.15

Penn had previously sold rights to large blocks of land, to be laid out in Pennsylvania, to three merchants of Krefeld and Kaldenkirchen—Jacob Telner, Jan Strepers, and Dirck Sipman.16 Each of them bought 5,000 acres. In June 1683, three more men bought tracts of 1,000 acres each—Govert Remke, Lenert Arets, and Jacob Isaacs van Bebber—all of Krefeld. These well-off buyers pledged to send colonists to settle the land, since Penn did not want large tracts to stand empty.17 Along with Benjamin Furley in Amsterdam, they served as facilitators for the Krefeld settlers, who bought some of their land. Telner sold some of his land to the op den Graeff brothers, who then sold 116 acres to Rynear Tyson. He also bought 50 acres from Lenert Arets.

The Germantown settlers faced hardships in their first few months and years. Their most pressing need after landing was for food and shelter. “Their first business, after their arrival, was to land their property, and put in under such shelter as could be found; then, while some of the got warrants of survey… others went diversely further into the woods to different places, where their lands were laid out, often without any path or road to direct them… A chosen tree was frequently all the shelter they had against the inclemency of the weather. The next coverings of many of them were either caves in the earth, or such huts as could be most expeditiously procured.”18 The historian was writing about the English Quakers who arrived in 1682, but the shared experience of settling in the new colony was common to all. The Germans probably helped each other build simple log cabins at first, a trick learned from the Swedes. Felling trees was risky; an early settler in Bucks County was killed when he misjudged the direction.19 These early houses were crude, but would later be replaced by houses built from the distinctive Germantown “glimmerstone”, a type of schist flecked with mica.20

To get through the first winter and spring, until they were able to harvest a crop, they needed to buy provisions. In a letter written for friends in Germany, Pastorius wrote from Philadelphia, “Two hours from here, lies our Germantown, where already, forty-two people are living in twelve dwellings. They are mostly linen weavers and not any too skilled in agriculture. These good people laid out all their substance upon the journey, so that if William Penn had not advanced provisions to them, they must have become servants to others.”21 They also got support from other Friends. In early 1684 the minutes of Philadelphia Monthly Meeting reported that “Derrick Isaacs, a Dutch friend of Germantown, acquainted this meeting of the wants of some of the dutch there.”22 The Quakers who came in 1682 and 1683 had the advantage of being able to buy food from the Indians and the Swedes, who were happy to provide deer, corn and other provisions.23 Although there was no starvation, there was still hardship. Some “grim humorists among them transformed the name into ‘Armen-town,’ or ‘Povertytown.’”24

Germantown was not on a navigable waterway; it was north of the falls of the Schuylkill.25 The road to Philadelphia was a rough dirt track, muddy when it rained. “trodden out into good shape” by frequently traveling back and forth.26 Wissahickon Creek, the nearest large stream, was almost a mile away, but there were closer small creeks, like Monoshone Creek (later called Paper Mill Run). It was probably the job of the women to go for water while the men cut down trees and built houses.27

When they had built their houses, it must have looked a little like the towns they had left. “For companionship as well as protection they built their first quaint houses in two rows, one of either side of the rough track. By day they would scatter to the lands in the rear of the houses; by night they would be in close touch with each other. This arrangement, so popular in the homeland, had even greater advantages in the new country.”28 Rynear and Margaret Tyson were not only surrounded by fellow Quakers speaking their own dialect of Dutch-German, they were also surrounded by family, both his and hers.

There is no record of the marriage of Rynear and Margaret. The early vital records of Abington Monthly Meeting, which handled the business of Germantown meeting, were not carefully kept.29 They were not married in Krefeld, and must have married soon after arriving in Pennsylvania, since their first son was born in 1686. Her first name was Margaret.30 (In 1727 Rynear and Margaret Tyson granted 250 acres of land in Abington to their son Isaac.)31 Her last name has often been said to be Kunders or Streepers.32 However, there is strong circumstantial evidence that she was the sister of the three op den Graeff brothers—Abraham, Herman, and Derrick—and the daughter of Isaac and Grietje.33 The evidence comes from several sources: the names of their sons, the close relationship with the op den Graeff brothers, the suggestion that they were cousins, and the judgment of German researchers who had access to original records.34 Margaret, daughter of Isaac and Grietje, is believed to have emigrated in 1683 with her three brothers. She is sometimes confused with two of her nieces, also named Margaret.35

Rynear and Margaret named their first son Mathias, for his father Matheis, and their second son Isaac, presumably for her father. They also named sons Abraham, Derrick, and Henry, presumably for her brothers.36 In May 1684, Rynear bought 100 acres in Germantown from Dirck and Herman op den Graeff. He paid them £3.37 The following year the three op den Graeff brothers sold 25 acres to the new arrival Peter Schumacher for £5.38 This is considerably more than they had charged Rynear. This favorable treatment would be explained if he were their brother-in-law.

There is some evidence that Margaret and Rynear were first cousins. Charles Kirk in 1892 wrote “I recollect hearing him [John Kirk] relate that his grand-father, Reynier Tyson, was not married when he first came to this country, and being disposed to marry his first cousin and our Discipline not allowing it, they made preparation to go back to Germany to accomplish their marriage, but Friends seeing their sincerity allowed them to proceed.”39 First-cousin marriages occurred occasionally among Friends, even though they were disapproved of.40 How could Margaret and Rynear be first cousins? Isaac Op den Graeff’s wife Grietje signed her name Grietje Peters at the 1681 wedding of her son Derrick. Some researchers believe that she was the daughter of Peter Doors, father of Matheis/Theiss Doors and Rynear’s grandfather.41 This leads directly to the idea that her daughter Margaret married Rynear Tyson, accepted by several researchers.42

In any case, Rynear and his wife settled into life in Germantown and started their family. Their house was used as a public center, for a meeting in 1692. He was elected as a burgess in 1692, 1693, 1694, and 1696. His fencing was found insufficient in 1696; and he performed jury service in 1701.43 As burgess he participated in the affairs of the town. For example, in 1692 Paul Wulff conveyed a lot to the commonality of Germantown for a burial ground. Reinier Tison signed the deed with his mark along with Peter Shoemaker and other burgesses.44 In 1689 he replaced Pastorius as a bailiff. In 1702 he sent his children to the school, taught by Pastorius. His children would learn to read and write, even if he could not.

Rynear was also active in Abington Meeting. In 1695 he was selected as an overseer of youth for Germantown. The overseers were responsible for guiding the youth in the Quaker way. As the minutes of Abington Monthly Meeting stated, “It is agreed upon at this Meeting that four Friends belonging to the Monthly Meeting, be appointed to take Care of ye Youth belonging to Each Meeting, as Concerning their Orderly walking, as becomes ye Truth they make profession of; according to ye good advice of Friends in an Epistle from ye yearly Meeting at Burlington 1694; whereupon Richard Wall is appointed for Cheltenham, Richard Whitefield for Oxford, John Carver for ye upper township, and Ryner Tyson for Ger.Town.”45 Rynear became an elder of the church. He represented Abington in the Quarterly Meetings in 1695, 1698 and again in 1728. He was several times appointed to visit with families; in 1735 this was with Thomas Roberts, whose daughter Mary was already married to his son Peter.

Rynear’s family could be a source of trouble to him. His sister Anna stayed in Germany with her husband Jan Streepers, while Jan’s brother Wilhelm came to Germantown. Wilhelm was supposed to manage Jan’s extensive land holdings in Pennsylvania, but relations between the two brothers deteriorated. Jan refused to give Wilhelm title to the 100 acres he had promised him, while Wilhelm delayed surveying Jan’s land and refused to pay the ground rents. Finally on May 13, 1698, Jan gave complete power of attorney to Reiner Theißen and Heinrich Sellen. He soon accused them of looking after the interests of Wilhelm and Lenssen rather than his. This may have caused Reiner to try to avoid further conflict. In March 1700 he declared before the bailiff that he relinquished the job.46

In 1683 Tyson bought 50 acres from Lenert Arets for 3 pounds Pennsylvania money. This was lot number five; his immediate neighbors were Arets and John Lucken.47 In 1684 Dirck and Herman op den Graeff sold 100 acres of land in Germantown to Tyson for 3 pounds Pennsylvania money. Around 1700 he bought 250 acres in Abington Township, Montgomery County and later resettled his family there. Why did he leave Germantown? He may have wanted more land for his sons. Jesse Tyson, a descendent, reminisced in 1870. “Reynear Tyson continued a resident of Germantown until it became thickly settled, then he sold his possessions there, which had become very valuable, and united with his wife’s property (for she had some property as well as spirit), he was quite independent. He purchased a large tract in Abington Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Here by industry, prudent land management, and judicious investments he accumulated much wealth and lived to good old age.”48

Rynear wrote his will in December 1741. He named his eight living children, but not his wife Margaret. She had died before him. He left a cash legacy to all of the children, plus his “Dutch books” to his daughter Elizabeth Lukens and his riding horse to his granddaughter Abigail. When he died in December 1745, the inventory of his estate was sparse, just the furnishings for one room, plus his apparel and a riding horse. He owned a bed and bedding, a chest of drawers, a cupboard, four chairs and a table, and an old white horse. 49 With the money that people owed him, the total came to £310.50 He must have been living with one of his children by then. A memorial of him published in The Friend, said that “He was innocent and inoffensive in life and conversation, and diligent in attending his religious meetings.”51

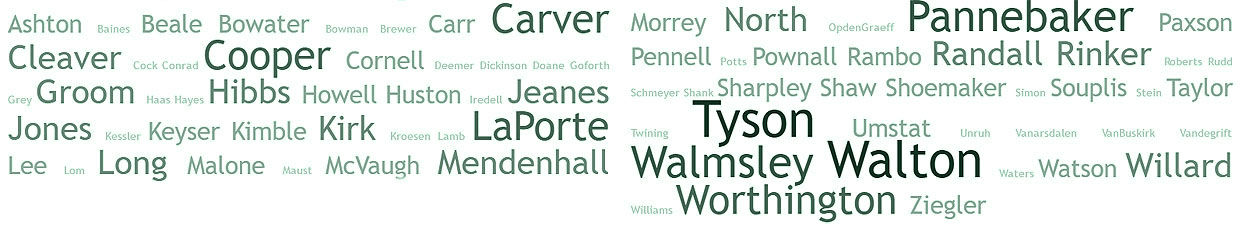

The family of Rynear and Margaret included nine children and over twenty grandchildren. Rynear and his sons owned large farms in Abington and Upper Dublin. On the list of landowners there in 1734, Rynear, Abraham, Isaac, John, Peter, and Derrick Tyson together owned over 500 acres. In addition to farming they also built limekilns.52 Their descendants intermarried with English Quaker families and stayed around Abington and Upper Dublin for generations.

Children of Rynear and Margaret:53

Mathias, born 6th month 1686, died 1747, married in 1708 Mary Potts at Abington Monthly Meeting. Mary was one of the orphan children of John Potts of Llangirig, Wales. Mathias and Mary lived in Abington, where he was a farmer. After Mathias died in 1727 she married Thomas Fitzwater, son of Thomas and Mary.54 Children of Mathias and Mary: Margaret, Mary, Rynear, John, Sarah, Elizabeth, Isaac, Martha, Elizabeth, Matthew.

Isaac, born 9th month 1688, died 1766, married in 1727 Sarah Jenkins, the daughter of Stephen and Abigail and granddaughter of noted Quaker Phineas Pemberton. They lived in Abington on a 200-acre tract.55 After Sarah died in 1759, Isaac married Lydia Robinson. Children of Isaac and Sarah: Thomas, Abigail, Lydia, Margaret, Isaac, Sarah, Israel, Rynear, Hannah, Levi.

Elizabeth, born 8th month 1690, married in 1710 William Lucken, son of Jan and Merken. They lived in Horsham, where William died in 1739 and left a will naming Elizabeth and nine children.56 Children: John, William, Mary, Sarah, Reinear, Mathew, Jacob, Elizabeth and Joseph.57

John, born 10th month 1692, died 1775, married in 1720 Priscilla Naylor, daughter of Robert and Elizabeth. They lived in Abington, where John is supposed to have discovered the limestone deposits and set up kilns for burning it to make quicklime.58 Priscilla was an elder of Abington Meeting. She died in 1760 and in 1764 John married the widow Sarah Lewis. John died in 1775. He left a will naming Sarah and eight of his children, but she had died in 1768. Children of John and Priscilla: Rynear, Elizabeth, Margaret, Sarah, John, Mary, Susanna, Joseph.59

Abraham, born 8th month 1694, died 1781, married in 1721 Mary Hallowell, daughter of Thomas and Rosamund. Like several of his brothers, Abraham lived in Abington and was a farmer. He died in 1781, and left a will naming his wife Mary and children Samuel, Abraham and Rosamund.60

Derrick, born 9th month 1696, died 1776, married about 1727 Ann Hooten. They lived in Hatboro, where he was a whip maker. Ann died in 1734 and he married Susanna Thomas in 1738. Derrick died in 1776, leaving a will naming his six living children.61 Children of Derrick and Ann: Deborah, Mary, Margaret, Benjamin. Children of Derrick and Susanna: Hannah, Jonathan, Daniel.

Sarah, born 12th month 1698, died in 1780, married in 1722 John Kirk, son of John Kirk and Joan (Ellet). They married at Abington; he had a certificate from Darby Mtg62. John died in 1759 and left a will naming Sarah and seven living children.63 She died in 1780.64 Children of John and Sarah: John, Rynear, Margaret, Elizabeth, Mary, Isaac, Jacob, Sarah.

Peter, born 3rd month 1700, died in 1791, married in 1727 at Abington Monthly Meeting, Mary Roberts, daughter of Thomas and Eleanor (Potts). They lived in Abington, but also owned land in Horsham. In 1769 he was one of the largest landowners in Abington township.65 He was active in Abington Monthly Meeting. Peter died in 1791, leaving a will naming his children Eleanor, Rynear, Margaret, Thomas, Peter.66 Mary had died before him, and he was living with one of his children (at age 91).

Henry, born 3rd month 1702, married in 1735 Ann Harker at Wrightstown Meeting. They moved to Wrightstown in 1738 but were back in Abington when the birth of their daughter Margaret was recorded there. He died after 1764 when he signed the wedding certificate of his son James. Children: Elizabeth, James, Margaret.

- William Hull, William Penn and the Dutch Quaker Migration to Pennsylvania, 1935, pp. 191-196; Claus Bernet, “Quaker Missionaries in Holland and north Germany in the late seventeenth century”, Quaker History, vol. 95(2), 2006, on JSTOR. ↩

- Hull, p. 234. ↩

- Hull, pp. 234-5. ↩

- The marriage certificate is unique, “so far as known, the extant marriage-certificate issued by a meeting of Friends on the continent.” (Hull, p. 209) Were there none from the early 20th century? ↩

- Hull, p. 209. ↩

- The ones who emigrated were Gertrude and her husband Paulus Kuster, Leentien and her husband Thonis Kunders, Elisabeth and her husband Peter Kurlis, Reynear, Agnes and her husband Leonard Arets, Herman. Once they got to Pennsylvania, Rynear used the surname Tyson, while Herman used Doors (with spelling variations). Cornelius Tyson, who emigrated around 1703, is frequently claimed as a brother of Reynier’s, but there is little evidence to support this. The names Rynear and Cornelius gave to their sons don’t match, except for Matthias or Theiss, which simply means that their fathers were both named Theiss. They practiced different religions. Cornelius was a Mennonite, while Rynear was a Quaker. They seem to have had no property dealings with each other. There is no mention of Cornelius in Niepoth’s research into the Dohrs family of Kaldenkirchen. ↩

- Samuel Pennypacker, Settlement of Germantown, 1899, p. 16. ↩

- James Claypoole’s Letter Book, 1967, edited by Marion Balderston. ↩

- Edward Hocker, Germantown 1683-1933, 1933. ↩

- Claypoole’s letters, p. 223. ↩

- Most of the ships that brought Quakers to Pennsylvania in 1682 and 1683 avoided serious illness. An exception was the ship that Penn himself came on, the Welcome. It was ravaged by smallpox. Another ship, the Morning Star, lost many passengers to dysentery. (Jean Soderlund, ed, William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania, 1983.) ↩

- Patrick Erben et al, The Francis Daniel Pastorius Reader, 2019, p. 179. ↩

- Thomas Brandt and Henry Gummere, Byways and Boulevards in and about Historic Philadelphia, 1925, p. 42. ↩

- Pastorius noted that his cellar could hold twenty people, “when the Crefelders lodged with me”. ↩

- The surveyors based their choice of land placement according to several factors. Obviously there needed to be vacant land of the right size. But they also placed people in family groups, in immigration groups (people from the same location in the old country), and in townships they were currently laying out. It is likely that new arrivals wished to go out with the surveyors to have some say in where their land was placed, but we have little information on the surveying process from contemporary accounts. ↩

- Samuel Pennypacker, Settlement of Germantown; Minutes of the Board of Property. There is a question about the date because of the ambiguity of dates in March in the old-style calendar. James Duffin, in Acta Germanopolis, 2008, gives the date of the conveyance to Telner, Strepers and Sipman as March 1683 instead of 1682. ↩

- When the land was laid out in Pennsylvania, Penn did not want their 18,000 acres (plus the 25,000 acres bought by the Frankfort Company, another group of wealthy Germans) to be laid out so close to Philadelphia. That is why Germantown was laid out for 6,000 acres. The other land that the buyers were entitled to would be laid out further north. In 1702 Mathias van Bebber obtained the rights to Sipman’s purchase and had a large tract laid out on the Skippack, known for a time as Bebber’s Township. (Ruth, Maintaining the Right Fellowship, 1984; Pennypacker, Acta Germanopolis) ↩

- Robert Proud, History of Pennsylvania, 1798, vol. 1, p. 224. ↩

- This was George Pownall, killed within a month after landing, who left a wife Eleanor. She gave birth to a son just two weeks later. ↩

- George Wertmuller wrote in a 1684 letter that “the houses in the country are better built than those within the city”. (Hull, p. 319) ↩

- Pastorius, “Positive information from America”, in Jean Soderlund, ed, William Penn and the founding of Pennsylvania, 1983, p. 356. Also in Julius Sachse, Letters relating to the settlement of Germantown, 1903. ↩

- Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, men’s minutes, available on Ancestry. ↩

- Peter Kalm, Travels in North America, Dover Edition, 1966, p. 266. He said that the Swedes bought corn from the Indians when they first arrived, but later produced a surplus themselves. ↩

- Edward Hocker, Germantown 1683-1933, 1933, reprinted 1997. ↩

- Penn refused to grant them so much land on the river. ↩

- Pastorius, in Soderlund, p. 356. ↩

- As John T. Humphrey noted, “Faced with the task of building a shelter and clearing the land of trees, settlers did not want to dig a well too!”, “Life in mid-18th century Pennsylvania”, formerly online, no longer accessible in 2020. ↩

- John Faris, Old roads out of Philadelphia, 1917, p. 204; Stephanie G. Wolf, Urban Village, 1976. ↩

- The minutes were gathered together and transcribed in 1718 by George Boone. They start in 1682 for the men, much later for the women. The early records of births, burials, and marriages are not well organized. Some events which are known to have happened were not recorded, such as the death of Grietje op den Graeff, mother of Margaret and her brothers. ↩

- This is obvious, even in the absence of records, given the number of Margaret’s in the third generation. In 1724 a “Margaret Tissen” subscribed toward building a wall around the Upper Germantown burying ground. This was probably the widow of Cornelius Tyson, since he was buried there. (Peter Keyser, “A history of Upper Germantown Burying Ground”, Penna. Magazine of History and Biography, 1884, vol. 8, p. 415. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book I-16, p. 416. Margaret signed the deed, while Rynear signed by mark. ↩

- Many secondary sources cite her last name as Streepers or Kunders. Rynear Tyson seems to have written to several of the other thirteen heads of families as “brother”, which could also mean brother-in-law. As Steward Baldwin noted in his online article on the Paxson family, “cousin” could mean “relative”, a “nephew” could be male or female, “son-in-law” commonly meant stepson, and in-law relationships were often not noted. (Steward Baldwin, “The Paxson Brothers of Pennsylvania”, Nat. Gen. Soc. Quarterly, 1995, vol. 83, pp. 39-43.) Even Margaret’s first name was uncertain for a time. Hull thought it was Maria. (Hull, p. 221) ↩

- Other researchers, including Cathy Berger and Maurine Ward, have come to the same conclusion about Margaret Op den Graeff. See Kathryn Sims, “Food for thought”, Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, 1993, vol. 10(2), also discussions on the Original-13 mailing list on 02 Dec 2001 and 14 July 2005. ↩

- Pesch noted that Reiner called the sons of Isaac op den Graeff his brothers. ↩

- Margaret Updegrave, daughter of Herman, one of the brothers, married Peter Schumacher Jr. in 1697. The other Margaret Updegrave, daughter of Abraham, married Thomas Howe. Both of these women were much younger than their aunt Margaret. ↩

- Henry was an anglicized form of Herman. ↩

- Acta Germanopolis, p. 450. ↩

- Acta, p. 465. ↩

- “Recollections of Charles Kirk”, 1892, mss. collection, Bucks County Historical Society, Spruance Library, Doylestown. ↩

- For example, Abington Meeting disowned first cousins John Lucken and his wife Sarah in 1741, but apparently reinstated them three years later. In 1742 the meeting noted that Samuel Hallowell had married his first cousin “some years ago”. ↩

- Peter was not a common name among the Mennonites of Krefeld and surrounding towns. An alternative explanation sometimes given is that the wife of Theiss Doors, whose first name was Neesen, was a daughter of Herman op den Graeff and a sister of Isaac op den Graeff. The only evidence for this is a dubious writing called the Scheuten manuscript, which is not considered a reliable source. ↩

- Dieter Pesch, editor, Brave New World: Rhinelanders conquer America, 2001. As part of an exhibit at the Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum, Pesch hired a German research firm to study the genealogy of the original settlers of Germantown and their relatives. See also the excellent summary of Randal Whitman, “The Settlement of Germantown 1683-1714”, online at: http://gmm.gfsnet.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/-settlement_of_germantown/The_SETTLEMENT_OF_GERMANTOWN_in_1683.pdf, accessed 2020. Also the article by Kathryn Sims, “Food for thought”, Krefeld Immigrants newsletter, 1993, vol. 10(2) and the subsequent discussion in the Original-13 mailing list by Maurine Ward (7/14/2005) and Howard Swain (02 Dec 2001). On the other hand, Chester Custer said her name was Kunders or Strepers. (Chester Custer, “The Kusters and Doors of Kaldenkirchen…”, reprinted in Krefeld Immigrants, 1986, 3(2). Wilhelm Niepoth, in his widely quoted “The Ancestry of the Thirteen Krefeld Emigrants of 1683”, PA Gen Magazine, vol. 3, said only that Rynear came to Pennsylvania in 1683. ↩

- Hull, p. 221. ↩

- Deed published in the Germantown Crier, 1987, vol. 39, p. 38. ↩

- Minutes of 29th 2nd month 1695, quoted in John Jordan, Colonial and Revolutionary Families of Pennsylvania. ↩

- Pesch. The entire museum exhibition documented in Pesch’s book was based on this quarrel, which took years to resolve. The Streepers papers are in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. ↩

- James Duffin, “Germantown Landowners, 1683-1714”, Germantown Crier, 1987, vol. 39. ↩

- Cited in Thomas Maxwell Potts, The Potts Family, 1901. Rynear’s oldest son married Mary Potts. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book H, p. 63. He left to his grandson Matthew Tyson (son of his son Matthias) £6; this to bar all heirs of Matthias Tyson from further claim; said Matthias having received his full share in his life time; to his sons, John, Abraham, Derrick, and Peter, six pounds each; to son, Henry, eight pounds; to daughters, Elizabeth Lucken and Sarah Kirk, six pounds each; to daughter, Elizabeth Lucken, “all my Dutch Books;” certain goods to be equally divided between sons, John, Abraham, Derrick, Peter and Henry, and daughters, Elizabeth Lucken and Sarah Kirk; to granddaughter, Abigail Tyson, “my riding horse;” residue of estate to his executor for his personal use, said executor to be his son, Isaac Tyson. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, 1745, #39, City Hall, Philadelphia. The inventory is not online. Rynear’s estate should not be confused with that of his grandson Rynear who died in 1750. ↩

- The Friend (Philadelphia 1857, vol. XXX, p. 229), quoted in Jordan. ↩

- The story was passed down that lime from their kilns was used for the mortar in Independence Hall. (E. Gordon Alderfer, The Montgomery County Story, p. 85.) Limekiln Pike in Upper Dublin was named for the limekilns of Thomas Fitzwater and the Tysons. ↩

- The lists of descendants are mostly taken from Charles Barker, “Descendants of Rynear Tyson”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1946, vol. 5. Some dates of death from Jordan. ↩

- The Fitzwaters and Tysons were the largest landowners in Abington for years. At the wedding of John and Mary in 1742, “Riner Tison, sener” was one of the signers. Rynear was not literate; someone must have written the name for him. (Samuel Traquair Tyson, A contribution to the history and genealogy of the Tyson and Fitzwater families, 1922) ↩

- 1734 tax list. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book F, p. 152. ↩

- Theodore Roosevelt was descended from the daughter Elizabeth and her husband Thomas Potts. They were his great-great-grandparents. ↩

- When mixed with water, quicklime makes mortar, useful for making stone buildings. (J. Carroll Johnston, “The Tyson Lime Kilns”, Old York Road Historical Society Bulletin, 1939, Vol. III, pp. 47-49) Johnston wrote that the line of John Tyson passed down the story that their lime was used for the building of Independence Hall. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book Q, p. 117. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book R, p. 553, not p. 425 as given in Jordan (Colonial Families of Philadelphia). ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book Q, p. 264. ↩

- Miranda Roberts and Gilbert Cope, Genealogy of the Descendants of John Kirk, 1912. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book L, p. 325. ↩

- Findagrave, citing burial records of Abington Friends. ↩

- 1769 Property Tax List of Philadelphia County and City. ↩

- Montgomery County estate file #RW6825. ↩

Hello. Have you ever come across the name Zephaniah Tyson born circa 1750 in Virginia? There is some speculation that he tied into this family…. But they also claim Cornelius is a brother to Reynier so I question their research .