Matthias Doors and his wife Neesen lived in the valley of the lower Rhine River as it winds its way north toward the Netherlands.1 The countryside is flat, with meadows, moors and heaths. It was dotted with small towns in the 1600s: Kaldenkirchen, Krefeld, Gladbach, Dahlen. Some of them were little fortified places with city walls. The walls were more than just boundaries. When Matthias and Neesen were growing up, the Thirty Years’ War was raging across the countryside. Mercenary armies devastated the land, looting from the inhabitants, leaving death, plague and famine.

When, in 1648, it had ended in exhaustion in the Peace of Westphalia, with hardly a stone on top of another, wolves roaming empty lanes, once-lush fields scrub-forested, and, in places, a tenth of the population left, the old Catholic German Empire had become a shell. Sixty-one cities and some 300 petty princes paid lip service to it, the map of their holdings a splotchy puzzle.

… However small, each such hereditary realm had its ruined castle and wasted fields. Villages, or even single farmsteads, called ‘hofs,’ might be divided among two or three baronies or church properties, each with its peculiar set of taxes, tithes, and excises. Small farmers might own modest plots, but their feudal landlords still lived by inherited, multiple, and endless revenues.2

It was a difficult time to live in the northern Rhineland, and doubly difficult for Mennonites such as Matthias and Neesen.

[The]…Mennonite inhabitants… did not fit any of the three religious categories—Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed—that were recognized under the treaties made at the end of the Thirty Years’ War. Nor were they appreciated by the clergy of the three official churches. These pastors felt that they had enough of a struggle to administer their decimated parishes without the irritating presence of people who looked after their own spiritual concerns, did not ‘go to church’ or the official statement, ‘let their children run about unbaptized,’ sometimes held ‘their services boldly in the forest,’ and even had the audacity to ‘solemnize marriages’ on their own.3

As a persecuted minority, Mennonites often moved from one area to another, seeking places where they were tolerated. At a time when the religion of the ruler became the official religion of the state (“cuius regio, eius religio”), they had no reliable protector. They were welcome in only a few areas, when the local ruler needed to repopulate the land. Matthias lived in Kaldenkirchen, near the border with the Netherlands. It was one of the centers of religious and political unrest, and Theiss and his wife had trouble with the authorities because of their religion.

Theiss was a son of Peter and Lyssgen Doors. He was baptized as a Catholic in 1614, but his mother Lyssgen was on a list of Mennonites by 1638.4 Theiss worked as a grocer, like his father and brother Reiner.5

“At least two large families of Doors lived in the Kaldenkirchen vicinity during the seventeenth century. One family lived in a marshy area near the village, whereas the Theiss Doors family lived in a little house on a small piece of land near the town wall. Theiss was a shopkeeper as was his father before him.”6 In 1652 he owned a house and lot and a small plot of arable land and some fishing rights.7 Perhaps Theiss sold fish in his shop. In larger medieval cities, merchants would cluster on streets or in quarters, based on their specialty. Butchers, cordwainers, and others would be found on the same street. Sometimes the clustering was dictated by needs, for example dyers needed running water and fishmongers were forced to live in less-central areas.8 Was Kaldenkirchen large enough to have areas where sellers would cluster?9

At some point Theiss married, probably about 1640. His wife’s family name is not known. Her first name was Neesen; the English equivalent would be Agnes. Some have speculated that she was a daughter of Hermann op den Graeff and his wife Grietje Pletjes. Hermann and Grietje didn’t have a daughter Neesen, but Theiss’ wife is claimed to be their daughter Hilleken, a claim that has no good evidence to support it.10

Whether Theiss was raised as a Mennonite, or whether he became one later in life, he was in trouble with the authorities in 1655, when his and his wife’s names appear in a court record.11 After the Treaty of 1648 the rulers of Jülich and Cleves were particularly hostile to Mennonites, many of whom fled to Krefeld, an “island of toleration”.12 Theiss and Neesen had stayed in Kaldenkirchen, possibly because of the difficulty of moving their business. In 1655 he was fined 100 gold guilders for a violation, probably refusal to pay taxes. He was unable to pay the fine and the authorities confiscated the goods in his shop.

In the middle of July 1655, the Governor of Brüggen, in whose jurisdiction Kaldenkirchen lies, is ordered by Duke Philip Wilhelm, the Count Palatine at Rhein, also Duke of Jülich, to collect a fine of 100 Gold Ducats from Theiß, for disobeying a submission. Should he disobey the ducal decrees, he would be denied to remain in the country any longer. He could have someone tend his house for him, the person couldn’t be a Mennonite or even have Mennonite servants, but rather had to be a local person and a citizen of Kaldenkirchen.13

The bailiff went into Theiss’ house to read the decree and argued with Neesen. She tried to tear the document from him and he struck her in the face. She was heavily pregnant at the time. To avoid further persecution, Theiss and Neesen took several steps. They entered their children in the Reformed Church school, then switched them to the Catholic school, and had their newborn Margarita baptized as a Catholic.14 Neesgen had “played with the idea of becoming Catholic, but only if she wouldn’t be forced to walk in the procession to the Niederrheinische well-known place of pilgrimage, the town of Kevela. That she didn’t have to, since the meantime she had joined the Reformed, the Calvinist faith.”15

“Theis Gohrs or Peterschen, born at Kaldenkirchen of Catholic parents, later adhering to the Anabaptist sect, joined the Reformed Church three months ago but did this only to escape persecution.”16 Then the Calvinist Pastor appealed to the Duke Philip Wilhelm about the treatment of Theiss and Neesen, and the Duke of Jülich, Philipp Wilhelm, ruled in his favor, allowing the family to stay in Kaldenkirchen and for their goods to be returned to them. They were to be recompensed for any goods already sold in Venlo, outside the country. The bailiff reported that he still had the 100 guilden and agreed to repay it to Theiss.

Whether their conversion was sincere or not, Theiss and Neesen did have their youngest child, Herman, baptized in the Calvinist church. As a descendant put it, “My (reputed) ancestor was baptized a Roman Catholic, persecuted as a Mennonite, joined the Reformed Church, and sent his children first to a Reformed Church school and then back to a Catholic School. He and his wife (Agnes) were probably devout Mennonites, but they kept changing their religious affiliation to avoid political and economic persecution.”17

The records of the family are incomplete, but Thiess and Neesen had at least nine children.18 There are numerous references to Theiss’ children in the church records, where they acted as sponsors for the baptisms of each others’ children.19 Most of them became Quakers and immigrated to Germantown, where they formed the nucleus of the town of Germantown.20

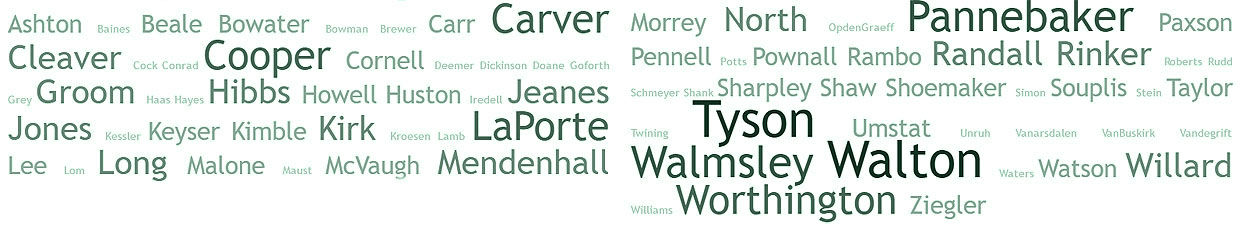

Children of Theiss and Neesen21

Anna (Enke), baptized in July 1641 at the Reformed Church at Kaldenkirchen, married first in 1663 Hendrich Kürlis, son of Johan and Mechtild, had two children with him, Mechtild and Jan. In May 1669 at the Reformed Church in Kaldenkirchen she married Jan Streepers, son of Wilhelm and Gertrude22. Anna and Jan did not immigrate. They were close to the families of Anna’s sisters, and Jan referred to them as his “five families” when he bought land in Germantown.23 Children of Anna and Jan: Leonhard, Hendrik, Katharina, Agnes, and Anneken.

Peter, born in 1643. No definite information is known about him. Some researchers have him marrying Judith Preyers about 1686.24

Gertrude, born about 1645. In 1668 she married Paulus Küsters, son of Arnold and Katherine, at the Reformed Church in Kaldenkirchen; in the marriage record they were both of Kaldenkirchen. In 1674, when their son was baptized in the Reformed Church, the pastor made a note that Gertrude was unable to use her mental faculties, and her mother served as sponsor. This may have been a ruse to allow her children to be baptized.25 Gertrude and Paulus emigrated to Germantown, although not on the Concord in 1683. Paulus died in January 1708 and named her as executor, but she died the next month.26 Children: Arnold, Johannes, Matthias, Rainer, Elisabeth, Hermann, Katherine.

Johanna, no further information

Leentien/Helene, born about 1650, baptized as an adult in 1670 at the Mennonite church in Goch. In 1677 she married Thönis Kunders, son of Coen and Anna (Entgen) at the Reformed Church in Kaldenkirchen.27 They came on the Concord in 1683. Thönis (Dennis) died in 1729 in Germantown. Many of the first settlers of Germantown attended his large funeral.28 Children: Jan, Konrad, Matthias, Anna, Agnes, Hendrik, Elisabeth.29

Elisabeth, married in 1675 Peter Kürlis, son of Johann and Mechtild from Waldniel30, came on the Concord. Peter was an innkeeper in Germantown. Children: Mechtild, Johannes, Agnes, Peter, Matthias.

Margarita, baptized in 1655 in Kaldenkirchen, no further information.

Maria, born about 1657, married Joachim Hüskes.31 Their daughter was baptized in 1674 at the Reformed Church in Kaldenkirchen. The record said, “’the little daughter of Jochim Huiskens and Maria Doors with the witnesses Thonis Huiskens and Nys Doors”.32 They did not immigrate. Children of Joachim and Maria: Ummel, Jan, Leonard, Mathias, Agnes, Elisabeth.33

Reinier, born about 1659, came on the Concord in 1683, married about 1685 Margaret Op den Graeff, possibly daughter of Isaac and Grietje.34 Reiner and Margaret settled in Germantown, later moved to Abington, Montgomery County, where he died in 1745. Children: Matthias, Isaac, Elisabeth, John, Abraham, Derrick, Sarah, Peter, Henry.

Agnes, married Lenhard Arets, son of Arendt and Katherine. They immigrated to Germantown, where Lenhard worked as a weaver. He died in 1714 and left a will naming his daughters.35 Children: Katharina, Margaret, Elisabeth.

Herman Dohrs, born about 1663, immigrated in 1684, died in 1739 in Germantown.36 He used the surname Dohrs or Dauers. He did not marry.37

- The name could be spelled in different ways, such as Daers, Dorss, or Dohrs. Here we will use the simplest spelling, that of Doors. The primary sources for the Doors family are the population lists of the German towns in the 1600s, lists of Mennonites, tax records, court records and church records. These are not easily available to American researchers, but are referred to in Wilhelm Niepoth, “The Ancestry of the Thirteen Krefeld Emigrants of 1683”, originally published in Die Hiemat, Krefelder Jahrbuch, translated by John Brockie Lukens, reprinted in PA Gen Magazine, vol. XXXI, 1908, also reprinted in Genealogies of Pennsylvania Families, vol. 3 (available on Ancestry). Another article that includes original research is by Chester E. Custer, “The Kusters and Doors of Kaldenkirchen, Germany, and Germantown, Pennsylvania”, PA Mennonite Heritage, vol. 9(3), 1986, reprinted in Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, vol. 3(2), 1986. Custer visited Kaldenkirchen and studied church records there, in Krefeld, and in the Dusseldorf State Archives of North Rhine Westphalia. Another source of original research is Dieter Pesch, Brave New World: Rhinelanders Conquer America, 2001, compiling work of the archivists at the Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum. Numerous others have discussed these families on web mailing lists and in issues of Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, a newsletter published from 1984 through 2004, edited by Iris Carter Jones. For a good discussion of this family see Iris Jones, “Dohrs or Theißens according to Neipoth”, Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, vol. 12(1), p. 15-18. ↩

- John L. Ruth, Maintaining the Right Fellowship, p. 26. ↩

- Ruth, p. 26. ↩

- Niepoth. It is not known whether Peter also became a Mennonite. ↩

- Niepoth. ↩

- Niepoth. ↩

- Niepoth, citing a Mennonite record of 1652. This is an odd source; it seems more like a tax list than a list of Mennonites. ↩

- Colin Platt, The English Medieval Town, 1976, p. 47. Platt was discussing Salisbury, Ipswitch, and London. There is no reason to believe that towns in Germany would be any different. ↩

- It is difficult to find population numbers for these towns. Niepoth estimated that Krefeld had a population of 1350 in 1650. (Wilhelm Niepoth, “The Mennonite Congregation in Krefeld and its relation to its neighboring congregations”, Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, 4(2), p. 56, translated by Charles Haller, originally published 1939. ↩

- There are two problems with this assertion. The first is that Hilleken is not the same name as Neesen or Agneesen. In a thoughtful discussion on the Original-13 mailing list (8 Aug 2001) Howard Swain pointed out that Hilleken can be the diminutive of names such as Hillegond, Mathilde, or Hilde, while Neesen, Niesje, Niesgen Neisken are diminutive of Agnietje. As Swain says, there is “no similarity between any of the Hilleken names and any of the Agnes names.” The other problem is that the only evidence for this claim is a suspect manuscript called the Scheuten Manuscript, passed down through some op den Graeff descendants. One of the three known copies seems to have been altered in order to extend the op den Graeff ancestry to the descendants of Theiss and his wife. (Iris Jones, Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, fall 1997 and 1998). Dieter Pesch, Brave New World, p. 218, lists her name as unknown. ↩

- The original is a 22-page handwritten document, according to Chester Custer. (“Kusters and Doors…”, 1986, p. 52) He gave the source as the State Archive of Nordrhein-Westfalen (North Rhine Westphalia) in Dusseldorf, in the records of Jülich-Berg, II, no. 252, Folio 80ff. It is widely quoted, but only a few researchers have actually seen it. Custer quotes from it. Niepoth does not cite the original document in his “Ancestry of the Thirteen Krefeld Emigrants of 1683”. He cites instead a 1931 article by Johannes Lenders that covers the court case. It seems likely, however, that Niepoth did see the original file at some point. He wrote “many small articles in various journals and left a mass of hand-written and typed notes which were given to the Stadtarchives in Krefeld (sic, actually in Dusseldorf).” (Charles Haller, “Wilhelm Niepoth/John Brodie Lukens References”, Krefeld Immigrants, vol. 13, p. 4.) In an article, “Dohrs or Theißens according to Neipoth”, in Krefeld Immigrants newsletter, vol. 12(1), Iris Jones quotes details from the court that were not in either Custer or Niepoth. She apparently got these from another article by Niepoth, referred to in Jean White’s book on the Descendants of Paulus and Gertrude Kusters, which included Chester Custer’s research. That research could have started with either Niepoth or Custer. The account of the court case given here is from Niepoth, Custer, and Jones. ↩

- Custer, p. 52. Krefeld was just outside the boundaries of Jülich-Berg-Cleves. ↩

- Iris Jones, “Dohrs or Theißens according to Neipoth”, Krefeld Immigrants newsletter, 12(1), p. 16. ↩

- Custer, p. 53; Niepoth. ↩

- Jones, p. 16. Some of this is clearly taken directly from the German. ↩

- Custer, quoting Niepoth. ↩

- John R. Tyson, August 7, 2001, no longer online in 2020. ↩

- Cornelius Tyson, who emigrated in 1703 and died in 1716 in Germantown, is frequently claimed as a brother of Reynier’s. However the names Rynear and Cornelius gave to their sons don’t match, except for Matthias or Theiss, which simply means that their fathers were both named Theiss. They practiced different religions. Cornelius was a Mennonite, while Rynear was a Quaker. They had no property dealings with each other. Rynear did not name a son Cornelius. Finally, there is no mention of Cornelius in Niepoth’s researches into the Dohrs family of Kaldenkirchen. ↩

- Niepoth. Also in Custer, p. 56. ↩

- They were not the first Germans in Pennsylvania, as in sometimes claimed. A man named Jurian Hartsfelder was living at Marcus Hook as early as 1677 (Records of the Court at Upland). He had 150 acres surveyed for him after the Quakers arrived in 1682. A few other Germans intermingled with the Swedes along the Delaware before 1682, such as Hans Geörgen. Penn’s private secretary, Philip Theodore Lehnmann, was apparently German. But the 1683 Concord immigrants were the first to form a settlement together. ↩

- Niepoth; Pesch; Krefeld Immigrants, vol. 12(1), pp. 15-18. The approximate dates of birth are from Pesch. Peter was named for Theiss’ father. They apparently did not name a son for Neesen’s father unless he was named Herman. (This is the only bit of evidence that Neesen might have been the daughter of Hermann op den Graeff, but it is very weak evidence.) Niepoth noted that the Mennonites had a strong tradition of handing down the grandfather’s name to a son, while the Reformed were less consistent. ↩

- Pesch, p. 244. ↩

- Pesch, p. 17, suggests that the five families were Tönis Kunders and wife Helene Doors, Peter Kürlis and his wife Elisabeth Doors, Leonard Arets with Agnes Doors, Reiner Theißen with Margret Isaaks op den Graeff. The fifth was either Herman Doors or Jan himself. ↩

- The family tree in Pesch’s book does not have this marriage. Pesch shows Judith Priors as marrying Johannes Bleickers/Blaker. On the other hand, Niepoth said that the Judith Preyers who witnessed the Quaker marriage ceremony in Krefeld in 1681 was a sister or cousin of Bleickers. He does not give a source for his inference. ↩

- Claudia Sullivan-Davenport suggested a “true translation: father was Roman Catholic; mother was member of Reformed Church, therefore her mother Agnes Doors was placed in her stead as sponsor”. (Her Ancestry tree page for Gertrude at: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/72329624/person/402036042439/facts, accessed May 2020. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book C, p. 72. His will was probated just three days after the will of Aret Klinken, a 1683 immigrant on the Concord, and just four days after Hyvert Papert, another Germantown settler. There must have been something contagious in the town that February. ↩

- Niepoth, p. 508. They may have married there so that their children would be recognized as legitimate. ↩

- Thomas Chalkley’s Journal. ↩

- “The Low-Rhenish Ancestors of Theunis Koenders/Kunders/Conradts/Heckers”, Krefeld Immigrants, 3(1), 1986, author unknown, possibly Wilhelm Niepoth. When Henry Kunders married Catharine Strepers in 1710 in Germantown, many of the early settlers signed their marriage certificate, including Reinier and Margret Theissen, Herman Dors, Peter and Elizabeth Keurlin, Jan and Mary Lucken. (PA Genealogical Magazine, vol. 2) ↩

- Pesch. p. 234; “Some background material on Peter Keurlis/Kürlis”, Krefeld Immigrants, vol. 13(9). ↩

- Pesch, p. 18, 219. He said they were married in 1674 at the Reformed Church of Kaldenkirchen and named two of their children Matthias and Agnes. This is fairly persuasive evidence of a relationship. ↩

- Post to Original-13 mailing list, 24 Oct 2006 , for the baptism. Some believe that she married Jan Lucken, son of Wilhelm and Adelheid, and came with him to Germantown in 1683. This idea probably started with William Hull, William Penn and the Dutch Quaker Migration to Pennsylvania, 1935. It was repeated by John Jordan, “Lukens Family”, Colonial Families of Philadelphia. The issue has been repeatedly discussed in the Original-13 mailing list, where there are arguments on both sides. Pesch has Jan Luckens marrying Maria Gastes, as do Niepoth and Chester Custer. Guido Rotthoff argued in 1982 that Jan married both women. (cited in Custer, p. 55 and Pesch, p. 18) Apparently some believe that Theiss’ daughter Margaret was actually the wife of Hüskes, leaving Maria free to marry Lucken. This is based on questions of spelling and difficult to resolve. It is generally thought that Margaret died young. ↩

- Pesch. ↩

- Not all researchers support this identity for Margaret, but the circumstantial evidence is very strong. She was not a Kunders or Streepers, as many claim. The received wisdom about the relations between the Concord group, before the research of Niepoth became known, claimed that Rynear Tyson was married to a sister of Kunders or Streepers, and that Kunders and Arets were married to sisters of Streepers. In fact the Tyson sisters were the center of the family interrelationships, not the Streepers sisters, as Niepoth showed. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book D, p. 16. ↩

- As it was described in a paper of the time, rather sadly, “One Herman Dorst near Germantown, a Batchelor past 80 Years of Age, who for a long time lived in a House by himself, on the 14th Instant there dyed by himself.” (American Weekly Mercury, Oct. 18, 1739, cited in Pennypacker, p. 55) ↩

- Hull believed that he was married to Trinken Jansen, since their names were close on the wedding certificate in the Quaker ceremony in Krefeld, but Niepoth showed that she was married to Abraham op den Graeff. ↩

This information is very well put together. I’m curious to know more about takingthelongerview.org. Is this a private individual sharing their research in a more pure way? Regardless, I appreciate it as I’m working to untangle and decipher the Reynier Tyson and Margaret _____ confusion. Your conclusion seems to make quite a lot of sense.

Thank you for your comment, Laura. I am a private individual, a person, and this blog is how I share my research. I also put it on an Ancestry tree.