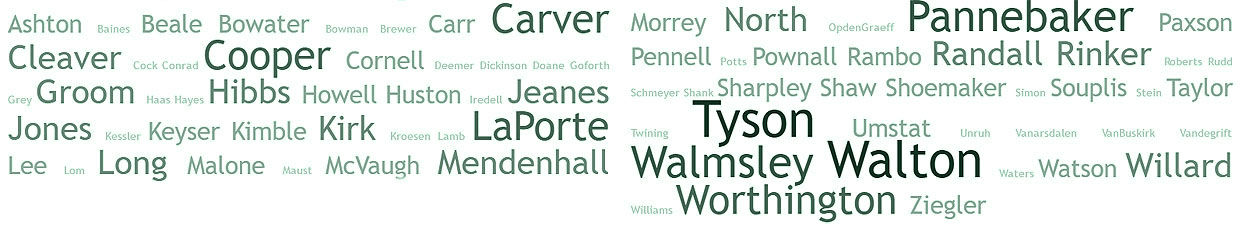

Ephraim was born on 25 Feb 1829, the youngest of six children of Rynear Tyson and Eleanor Jeanes of Upper Dublin, Montgomery County. In June of 1831 his father died, leaving Eleanor with a family of small children: Edmond, Peter, Sarah, Seth, William and Ephraim. She must have gone to live with relatives. Five of the children lived to adulthood, but only two of them—Ephraim and his older brother Edmond—married and had children.1 Ephraim and his siblings must have struggled to find work, and several of them went to the crowded city, where they were susceptible to diseases of poverty. Edmond moved to Philadelphia and became a stationer. He died in his early thirties and all three of his sons died of consumption. Sarah went to Philadelphia and lived with her cousins Seth and Rebecca Holt. Sarah worked as a milliner and died of consumption at age 40. Ephraim’s brother Seth went west in the Gold Rush, lived in Nevada, then in Nevada County and Yuba County, California. William never married and died in the household of his nephew William.

In 1850 Ephraim was living in Moreland with the household of Samuel Robinson. They were both shoemakers; Ephraim was learning the trade from the older Samuel.2 Ephraim must have moved to Germantown by 1855, when he married Anna Maust, daughter of Peter Maust and Anna Unruh.3 She was from two German families, with no Quaker background. In 1860 Ephraim and Anna were living in Germantown, probably on land inherited from Anna’s father.4 Ephraim was 31 years old, working as a cordwainer. Anna was 26. Ephraim’s widowed mother Eleanor was living with them. The next year Ephraim, then living in Bristol Township, bought two lots in Upper Dublin from the estate of William Carney. Ephraim paid $3,130 for the two lots, for a total of fourteen acres.5 He and Anna moved there, and in 1862 he was taxed there as a maker of boots and shoes.6 He registered for the Civil War in June 1863.7 In 1868 Ephraim and Anna moved again, probably for the last time. They bought a tract of 26 acres from William and Martha Palmer for $6,200, on the road from Horsham Meeting to Dreshertown.8 A day before they had sold the two lots in Upper Dublin to Jacob McVaugh for $4,000.9 In 1870 they were in the Horsham house, just off the Susquehanna Road, with five children. Eleanor was next door in a separate house.10 By 1880 they had seven children at home.11

Ephraim died in 1897. According to his obituary, “his death was not looked for, as he was up and around the house, but was ailing somewhat…an industrious and prosperous farmer…a member of Eagle Lodge, No. 222, I.O.O.F.”12 In 1900 Anna was still living on the Horsham farm, with three of her children: John, Hannah, and Charles.13 Her son William and his wife Catherine were nearby. She joined the Baptist Church, possibly after Ephraim died, since he had attended Friends meetings.14 Anna died in 1915 and was buried at Hatboro, with Ephraim, William and Catherine, Robert, and several grandchildren.15

Children of Ephraim and Anna:16

Ida Ann, born in 1858, died in 1941, m. William DePrefontaine, the son of John and Mary. They lived in Upper Dublin where William was a farmer. By 1920 they had moved to Philadelphia, where William ran a hardware store and his daughter Minnie was a saleslady in the store. Children: Ethel, Minnie.17

Edmund Jeanes, born in March 1860, lived for only twelve days

Samuel Maust, born in 1861, died in November 1917, married in 1894 Amelia Mackel. In 1900 he was farming in Moreland Township, Montgomery County. After he died Amelia must have gone to live with relatives, since she died in Southampton, Bucks County, in 1922. They are buried at Hatboro. Children: George, Amelia, Winfred, possibly Louisa.18

Robert Ephraim, born in 1864, died in 1946, married in 1887 Ellen Sutton. She died in 1897 and a year or two later he married Mary Weaver. In 1900 Robert was a farmer in Horsham Township, Montgomery County. Mary died in 1936. They are buried at Hatboro. Children: Ida, Florence, Walter.19

William Jeanes, born in 1866, died in 1947, married in 1889 Catherine Rinker, daughter of Francis and Catherine. They lived in Horsham, at the corner of Easton and Dresher Roads, right across from the Horsham Friends Meeting House.20 In 1900 they were there with their four oldest children and Catherine Rinker, Catherine’s mother. In 1910 they were still farming in Horsham, with five of their children at home. 21 Ten years later they were living on their farm in Horsham. Their son Raymond, age 24, was married but still living at home with his parents. In 1930 they were still on the Easton Road in Horsham.22 William died on March 24, 1947, Catherine died on June 25, 1950. They are buried in Hatboro Cemetery. Children of William and Catherine:23 William Francis, Ralph Steward, Raymond LeRoy, Harry Edwin, twins Katie and Anna, Mildred Evelyn, Earl Jeanes.

John Maust, born in 1868, died Nov 25, 1925, did not marry, lived on the same property as William, worked as a construction worker. He died of fractured skull and broken neck after an “unavoidable” car accident.24 He was buried at Hatboro.

Thomas Edwin, born in Dec 1870, lived for only five weeks.

Albert Alvin, born in 1872, died Oct 10, 1938, married in 1894 Kate DePrefontaine, daughter of Charles and Emma. They lived in Horsham where he was a farmer25 Albert was buried at Rose Hill, Ambler.26 Children: Emma, Harold, A. Russell.

Anna May, born in 1875, died in 1957, married in 1894 Jacob Refsnyder, lived in Camden, later in Cheltenham, where he was a steamfitter.27 Jacob died in 1925. Anna lived until 1957. They are buried at Hatboro. Children: Edith, John, Oliver, Anna, Ella, Edgar, Robert.

Hannah, born in 1877, died in 1958, married Jesse Lenhart, probably the son of Morris and Lettia.28 In 1920 they were living in Philadelphia where he was a motorman. In 1920 they were living in Germantown.29 Jesse died in 1945. Hannah died in 1958. They were buried at Hatboro with their daughter Florence, who lived for a year.30

Charles Pattison, born in Nov 1882, died in Oct 1946, m. Anna Frances Wheatland about 1904, lived in Abington. He worked as a gardener for a private estate, moved to San Diego briefly, then came back to Montgomery County and worked as a inspector for a bearing manufacturer.31 Anna died in 1943 and in 1945 Charles married Olive Houpt, daughter of Benjamin F. Houpt and Ella Maria Rinker. Olive’s sister Catherine P. Rinker, was married William J. Tyson, Charles’ brother. Olive was a spinster who married late in life, but lost her husband after only one year of marriage. Charles died in 1946 and was buried at Hillside Cemetery with his first wife Anna.32 Olive died in 1955 and was buried at Rose Hill Cemetery in Ambler with her parents.33 Children of Charles and Anna: Charles E, Katherine.

- There are no definite records of Peter after 1831. ↩

- 1850 census, Moreland, Montgomery County, image 20. In the 1860 census Samuel Robinson was still in Moreland, a shoemaker, with a new apprentice, Peter Tyson, age 19. Unless the age is off by ten years, this can’t be Ephraim’s brother Peter, listed in an Orphans’ Court petition in 1831, when their father Rynear died. ↩

- They were married on 27 December 1855 by “Roert” Young, according to a record in a family Bible, sent by Donald Kellogg to me in 2003. He did not give a source. ↩

- 1860 census, Philadelphia, ward 22, image 310. His name was spelled Ephram. The household also included Jacob Fisher, age 28, farm laborer, and William H. Tyson, age 17, apprentice cordwainer. William Tyson, age 57, a stone mason, was nearby. The age suggests this was not Ephraim’s brother William, who was about 32 when the census was taken. ↩

- Montgomery County deeds, Book 122, p. 210, 2 April 1861, Ann Carney to Ephraim Tyson. ↩

- IRS tax lists, 1862, Division 9, District 6, image 464, on Ancestry. Ephraim had to pay 10 cents tax. ↩

- Civil War Registration Records, 6th Congressional District, image 503, on Ancestry. ↩

- Montgomery County Deeds, Book 155, p. 495. ↩

- Montgomery County Deeds, Book 155, p. 477. Jacob McVaugh may have been a cousin. Eleanor Jeanes Tyson, Ephraim’s mother, was the daughter of William Jeanes and Elizabeth McVaugh. The exact relationship has not been traced. The McVaugh family begins with Edmond McVaugh, the 1682 immigrant, but the records of his descendants are sparse. ↩

- 1870 census, Montgomery County, Horsham, image 3. ↩

- 1880 census, Horsham, district 9, image 25. Two of their children, Edmund and Thomas, had died in infancy. Samuel, the oldest surviving son, was living in Abington, in the household of George Williard, working as a laborer. Another children, Charles P, the youngest, was not born until 1882. ↩

- The Eagle Lodge was part of the International Order of Odd Fellows, a fraternal organization. ↩

- 1900 census, Horsham, ED 207, image 2. ↩

- Ellwood Roberts, Biographical Annals of Montgomery County, vol. 2, 1904, written after Ephraim’s death. ↩

- There are ten Tysons buried together: “Ephriam”, Anna, William J, Catherine, Harry E. 1897-1918, Ida May 1889-1924, Mary E. 1880-1936, Robert E. 1864-1946, Walter 1900-1902, Baby boy 1944. ↩

- From the 1870 and 1880 (image 25) census, Helen Tyson’s recollections, and the Bible records passed to me from Donald Kellogg. William was her father-in-law. I have a daguerreotype that shows a young couple and their young son. From the 1850’s heyday of the type, this could be Ephraim and Anna. Note: Ephraim spelled his name “Ephraim” in the family Bible; it was “Ephriam” in the cemetery records. ↩

- I have a lovely picture of Minnie, with her hair worn in two long coils. ↩

- George died as an infant of cholera. (undated newspaper clipping). The daughter Louisa is a suggestion by Donald Kellogg, personal communication 2003. He was a descendant of Samuel and Amelia. The daughter Amelia married William Schumacher and died in 1917 at age 20 from complications of childbirth. (PA State Death Certificate for Amelia Schumacher. The name of her husband is from the Findagrave entry for Amelia, in Hatboro Cemetery). ↩

- 1910 census. ↩

- In the 1920 census George Maust was living very close to William in Horsham; is this a coincidence or inherited family properties? ↩

- 1910 census, Horsham, image 2. ↩

- 1930 census, Montgomery County, Horsham, ED 46, image 63 and 65, indexed as Lyson. Their son Earl was living with them, working as a payroll clerk in a hosiery operation. Raymond and Helen had moved out, but were living close by on the Easton Road. ↩

- Recollections of Helen Worthington Tyson, wife of Raymond L. Tyson. ↩

- His Pennsylvania state death certificate. ↩

- Date of marriage from PA County Marriages 1885-1950, on FamilySearch. ↩

- His PA death certificate. ↩

- 1900 census, Cheltenham, Dist. 198, image 7, Jacob Reifsnyder, age 29, a steam fitter, with children Edith and John E. In the 1910 census, still in Cheltenham, district 68, image 19, with children Edith, John, Oliver, Anna, Ella. ↩

- In the 1900 census there was a Jesse B. Lenhart age 29 living with his parents Morris and Lettia on the same page of census as Anna Tyson and her children John Hannah and Charles. Jesse was working on his father’s farm. ↩

- 1920 census, ward 22, district 574, image 48. Jesse was a motorman. They had no children at home. They were living next door to a Catholic convent. ↩

- She may have been their only child. They had no children listed in the census of 1920 or 1930. ↩

- Federal census for 1920, Abington, district 67, image 8; census for 1930, Abington, District 10, image 51; San Diego city directory 1938; Federal census 1940, Horsham, S.D. 17, image 18; World War II Draft Registration, April 1942. In 1920 Charles was a gardener for a private estate, apparently the summer home of James S. Merritt, whose household also included a cook, chambermaid, nurse and waitress. ↩

- PA State Death Certificate for Charles P. Tyson, on Ancestry. It gave the names of his parents, his wife, and the dates of birth and death and burial. Hillside Cemetery is in Roslyn, Montgomery County. His estate was administered in Montgomery County by Olive E. Tyson. ↩

- PA State Death Certificate for Olive E. Tyson. It gave the names of her parents, dates of birth and death and place of burial. The burial details are from Findagrave. The four Houpts were buried with one tombstone. The name Houpt is at the top, with the names underneath, including Olive E. ↩