Peter Doors and his wife Lyssgen (Elisabeth) lived in Kaldenkirchen, in the lower Rhine in the late 1500s and early 1600s.1 This was a border town, just a few miles from the Netherlands, where the Dutch had been fighting for their independence from Spain since the 1560s.2 It was a time of upheaval and religious wars, when different religions vied for the allegiance and faith of the people. We can assume that Peter and Lyssgen were resilient in their ability to make a living and raise a family.

In the 1600s Germany was not a unified country. It was a patchwork of hundreds of duchies, counties, margraveshafts, and other jurisdictions, each ruled over by different rulers. Sometimes a few villages were under the control of a count and in other cases hundreds of towns might be under the control of a neighboring duke.3

Kaldenkirchen belonged to the Duchy of Jülich, also known as Jülich-Berg. The dukes were historically wealthy, because the flat country of the northern Rhineland was fertile.4 At the time when Peter and Lyssgen married, it was ruled by the Duke Johann Wilhelm, son of Wilhelm the Rich. When Johann Wilhelm died childless in 1609, the duchy was plunged into a struggle for the succession, which helped lead to the Thirty Years’ War in 1618.5

Peter and Lyssgen were probably not directly affected by the wars. “The civilian population—except in the actual area of fighting—remained undisturbed at least until the need for money caused an exceptional levy on private wealth. Even in the actual district of the conflict the impact of war was at first less overwhelming than in the nicely balanced civilization of to-day. Bloodshed, rape, robbery, torture, and famine were less revolting to a people whose ordinary life was encompassed by them in milder forms.”6

Life in early modern Germany was very different from ours, almost beyond our ability to imagine. “Underneath a veneer of courtesy, manners were primitive; drunkenness and cruelty were common in all classes, judges were more often severe than just, civil authority more often brutal than effective and charity came limping far behind the needs of the people. Discomfort was too natural to provoke comment; winter’s cold and summer’s heat found European man lamentably unprepared, his houses too damp and draughty for the one, too airless for the other.”7

The family surname in the late 1500s was Doors (sometimes spelled Daers, Dorss, Dohrs, or some other variation). An early record of Kaldenkirchen suggests that the family had been there for generations.8 A population record for the town in 1473 to 1475 includes Peter an gen Daere.9 In March 1615, a Tisken Doors died in Kaldenkirchen.10 If Tisken was a form of Theiß, short for Mathias, then Tisken might have been the father of Peter Doors.11 Tisken was a Catholic, and Peter was too, at least initially.

Peter was a grocer. In some records he was called “an gen Door alias Küppers”. “Küpper” could mean barrel-maker (like the English name Cooper), but apparently could also mean merchant (possibly someone who sells goods in barrels). Both of his sons were listed years later as retail merchants, presumably inheriting the business from their father Peter.

By 1638, Lyssgen appeared in a Mennonite record.12 In a land where most people were Catholic or Reform, she had turned away from the official religions in favor of an often-persecuted sect. Mennonites or Anabaptists, as they are also called, followed the teachings of Menno Simon. They rejected infant baptism, refused to fight, and often did not respect the authority of civil governments. It is not clear whether Peter shared Lyssgen’s faith, but at least one of their children, Mattheis, became a committed Mennonite.

Peter died in December 1638, possibly of bubonic plague, “which raged in that area at the time”.13 A Mennonite record made at the time referred to “Lyssgen Daers widow whose husband died a few days ago. Their property, after all debts are paid off out of principal, shall be worth about 36 Reichstalers.”14 Did Peter’s sons inherit his property? Presumably they did, since two of them were in business in Kaldenkirchen for years to come. It is not known when Lyssgen died. Peter and Lyssgen are believed to have three sons and at least one daughter. Perhaps she lived with one of them after Peter died.

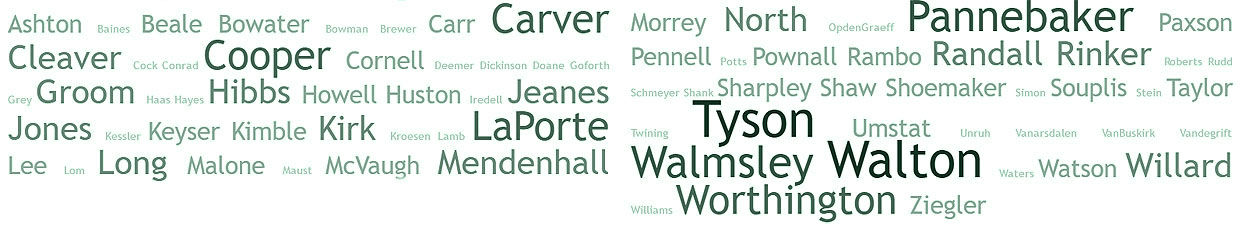

Children of Peter and Lyssgen15

Reiner, m. Trinken —, died after 1663, lived in Kaldenkirchen. In 1638 he was listed as owning three acres of orchard and fields, and in 1652 as a retail merchant, with two acres and about thirty rothen, worth about 220 Reichstalers.16 He had a daughter Trinken (Katharina) baptized as an adult in 1663 at the Reformed Church in Kaldenkirchen. The witnesses were Jan Strepers and Neesen Doors, wife of Theiss.17 The records of the Reformed Church are lost before 1663; Reiner probably had other children as well.18

Peter, baptized 1609, no further record.

Mattheis (Theiss), christened at the Catholic Church in 1614, married about 1636 Neesen —, became a Mennonite19, died after 1663. In 1652 list he was listed as a “retail merchant, with a building lot and small house and a quarter of an acre of arable land and alongside it a quarter of an acre of fishery rights, worth altogether about three hundred and fifty Reichstalers”.20 The fishing rights were presumably in the Königsbach creek, which flows through the town and into the Nette, which in turn flows into the Rhine.21 Theiss and his wife Neesen were Mennonites and faced fines and penalties for their refusal to pay the war tax. They raised a large family in Kaldenkirchen. It is not known when Theiss or Neesen died. Children: Anna, Peter, Gertrude, Johanna, Leentien, Elisabeth, Margarita, Maria, Reinier, Agnes, Hermann.

(probably) Grietjen, married Isaac Op den Graeff, son of Herman and Grietjen22, a Mennonite23. After Isaac died in 1679, she immigrated in 1683 with her three sons and a daughter to Pennsylvania, and died soon after their arrival. Known children of Isaac and Grietjen: Adolphus, Dirck, Herman, Abraham, and Margaret.24 Adolphus stayed in Germany, while the others immigrated.

- The name could be spelled in different ways, such as Daers, Dorss, or Dohrs. This narrative uses the simplest spelling, that of Doors. The primary sources for the Doors family are the population lists of the German towns in the 1600s, lists of Mennonites, tax records, court records and church records. These are not easily available to American researchers, but are referenced in Wilhelm Niepoth, “The Ancestry of the Thirteen Krefeld Emigrants of 1683”, originally published in Die Hiemat, Krefelder Jahrbuch, translated by John Brockie Lukens, reprinted in Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, vol. XXXI, 1908 and in Genealogies of Pennsylvania Families, vol. 3 (available on Ancestry). Another article that includes original research is by Chester E. Custer, “The Kusters and Doors of Kaldenkirchen, Germany, and Germantown, Pennsylvania”, PA Mennonite Heritage, vol. 9(3), 1986, reprinted in Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, vol. 3(2), 1986. Custer visited Kaldenkirchen and studied church records there, in Krefeld, and in the Dusseldorf State Archives of North Rhine Westphalia. Another source of original research is Dieter Pesch, Brave New World: Rhinelanders Conquer America, 2001, compiling work of the archivists at the Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum, who documented the immigrants from the Rhineland in preparation for an exhibit at the museum. Numerous others have discussed these families on web mailing lists and in issues of Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, especially relevant is Iris Jones, “Dohrs or Theißens according to Neipoth”, Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, vol. 12(1), p. 15-18. ↩

- The Twelve Years Truce was established in 1609, but it only held until the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War in 1621. (Wikipedia entry for Eighty Years’ War, also called the Dutch War of Independence). ↩

- Gary Horlacher, The Palatine Project, online at palproject.org, accessed 2004, no longer online in 2020. ↩

- The northern part of the Rhine is called the Lower Rhine, because the river starts in Switzerland and flows north, losing altitude as it goes. North Rhineland Westphalia, where Krefeld and Kaldenkirchen are found, lies north of the Palatinate, forming the western boundary of present-day Germany. ↩

- Wikipedia entry for John William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. ↩

- C. Veronica Wedgwood, The Thirty Years War, 1938, reprinted 2005, p. 14. ↩

- Wedgwood, p. 15. ↩

- Wilhelm Niepoth, “The Ancestry of the Thirteen Krefeld Emigrants of 1683”. ↩

- Dieter Pesch, compiler, Brave New World: Rhinelanders Conquer America, 2001, p. 218-220, family tree of Doors/Theißen. Pesch and the team of researchers at the Rheinische Freilichtmuseum in Kommern gathered church records, population records, tax records, lists of Mennonites, and more, and assembled family trees of the original 13 families who settled Germantown, as well as many of their relatives and associates who stayed behind in Germany, providing the data for the family trees in the book. In a puzzling omission, the book includes a list of Doors families there in 1624-26, those of Ummel, Goert, and Johan. Shouldn’t Peter’s family be there as well? (p. 218) The “an gen” portion of the Peter’s name is also puzzling. Charles Gehring, who translated thousands of pages of 17th century Dutch documents for the New Netherlands Project, commented on the name Wilhelm an Gen Eick (unrelated to the families in this narrative). “Unless I missed some divergent or parallel development in the system of definite articles in Early New High German when I studied Germanic Linguistics, the name should be recorded as Wilhelm an den Eick. It would appear that the D in the Frakturschrift has been mistranscribed as a G. This should be noted, as “an Gen Eick” makes no sense.” Is it possible that even Pesch’s team of researchers have made an error for “an den Doors”? ↩

- His death is variously given as March 1614 and 1615. Before 1752, the year started in March, and a March date was ambiguous. It was presumably 1614/15, that is 1615 by our (Gregorian) calendar. ↩

- This relationship is accepted by Dieter Pesch’s research group and by Jean White, in The Descendants of Paulus and Gertrude Kusters of Kaldenkirchen, Germany and Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1991. ↩

- Pesch, p. 218. ↩

- White, p. 48. ↩

- Niepoth. ↩

- The identity of Peter and Theiss are from baptismal records. The identity of Reiner come from tax lists showing his presence in the right place and the right time. In addition, when his daughter was baptized at the Reformed Church in 1663, Theiss’ wife Neesen was a witness. (Niepoth) The placement of Grietjen in this family is uncertain. She used the patronymic of Peters when she signed a Quaker marriage certificate in 1681. (William Hull, William Penn and the Dutch Quaker Migration, 1935) ↩

- Niepoth. A rood is a quarter of an acre. The 1652 list was made by bailiff of the district of Brüggen according to Pesch, p. 20. ↩

- Niepoth. The Strepers family became related to the family of Theiss Doors when Anna Doors, daughter of Theiss and Neesen, married Jan Strepers in 1669. But the families may have been related further back, as suggested by this baptism sponsorship. ↩

- Pesch, p. 20. ↩

- In a record of the Catholic church in Kaldenkirchen, Theiß was listed as the son of “Pietter agen Door and Leißken”. (Krefeld Immigrants and their Descendants, vol. 4) ↩

- Niepoth. ↩

- In 1970 Kaldenkirchen was merged other towns to form the city of Nettetal. ↩

- As one writer put it, “Krefeld had a larger thriving Mennonite community than often comes across from descriptions of the history of the group who left for Germantown, and they had close relations with the Mennonite community in Cresheim or Kriegsheim. … This Margaret was the daughter of someone named Peter. It could have been any Peter, and it could well have been a different Peter. Theiss’ father was Peter Doors, and he is the only Peter in the area I’ve seen any mention of, anywhere.” (“Ancestors of Russell D. Smith”, online at https://sites.rootsweb.com/~villandra/fatheri/index.htm, accessed May 2020) ↩

- There is no proof of her identity as a daughter of Peter and Lyssgen. The circumstantial evidence is from her patronymic (when she signed the Quaker wedding certificate) and the tradition that Rynear Tyson and Margaret op den Graeff were first cousins, which could be explained if his father and her mother were both children of Isaac op den Graeff and his wife Grietje. (Maurine Ward, post to Original-13 Mailing List, 7/14/2005 and Krefeld Immigrants, vol 10(2), pp. 58-60.) ↩

- There may have been other children as well, but they almost certainly did not have the seventeen children sometimes attributed to them. ↩