Peter and Elizabeth Pannebaker

Peter Pannebaker was born on March 8, 1710 in Skippack, the second son of Hendrick and Eve Pannebaker, one of eight children. The area was heavily German; his family was surrounded by other German families. At the time Peter and his siblings were growing up there were few roads; their father Hendrick was a surveyor and laid out many of the roads in upper Philadelphia County.1 Like his four brothers, Peter grew up to be a miller. He owned land on the Skippack and Perkiomen and operated a fulling mill, for dyeing cloth, with an experienced fuller, William Nenny, to run the mill.2

In 1733 Peter married Elizabeth Keyser, daughter of Peter and Margaret. (Her sister Annetje would marry his brother John a few years later.) She was from a Mennonite family, and it is likely that Peter and Elizabeth worshipped in the Mennonite church. (They were buried in a Mennonite cemetery). 3 Elizabeth’s father Peter had come to Germantown as a boy with his father in 1688. Peter married Margaret Souplis, and they had eleven children. Elizabeth was the seventh, born in January 1713/14.

Peter became the wealthiest and most influential of his family. In 1738 and 1739 he was in the business of hauling iron fom Reading furnace and Coventry forge, Chester County, to Philadelphia.4 In 1741 he bought 240 acres on the Skippack from his father Hendrick, and erected a mill, which he later sold to his brother Jacob. (He later served as the executor of Jacob’s estate.) In 1756 he was assessed for 500 acres, 100 acres cleared, 25 acres in corn, five horses, two mares, 15 sheep, 14 horned cattle and 300 acres of unimproved land.5 An account book in his handwriting showed charges for sugar, tea, coffee, and molasses, suggesting that he kept a store.6 An account book of a Philadelphia merchant in 1741 shows sales to Peter of shoe buckles, pins, and six hats.7 Eventually he would own property valued at over £4000.

As a wealthy man, Peter was a leader in the German community, with some political involvement. In 1754 he was elected as an assessor for Philadelphia County.8 The same year he, along with Henry Muhlenberg and 30 other leading Germans, signed a letter to the new governor Robert Morris, assuring him of their loyalty to the King. They were responding to “some Spirit” who had accused them of conspiring with the French against the English government. This unnamed person was none other than Benjamin Franklin. Initially sympathetic, Franklin had turned against the Germans during the 1740’s, because of their pacifism and their non-English ways, saying that they were “herding together to establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours”. He added that the German men liked their women fat and strong, valued for the work they could do. Franklin was a well-known figure and his views were known, and obviously resented. In 1764 he was defeated in the election for the Assembly, probably because of German opposition.9

In 1747 Peter and Elizabeth bought 500 acres, a house, and a mill from Henry Pawling and the heirs of Isaac Dubois. The Pawling and Dubois families had owned the property since 1730, buying it from Hans Jost Heyt.10 Fifteen years later Peter and Elizabeth sold 115 acres and the mill, part of the 500-acre tract, to Adam Prutesman. The deed included an unusual stipulation that Prutesman was not to keep a tavern on the land or in the mill “nor suffer one to be kept by any other person on the premisses.”11 Peter and Elizabeth lived on the remaining land, in the house that Heyt built, which they expanded. They owned a tall clock (still at the house now) and a large Bible with brass clasps (also at the house). When Peter died in 1770, he left the plantation to his youngest son, Samuel, who was to keep Elizabeth on it for the remainder of her life. (In fact she outlived Peter by over 25 years.) When Elizabeth Drinker stopped there in August 1771, she wrote in her diary that they “dined in a Mill-House at Peter Pennybaker’s, boyl’d mutton and old kidney beans, eat very hearty.” Apparently it was being kept as a public house then. It was well-situated, on a main road from “the upper country” to Philadelphia. This might have been the Perkiomen property, but Peter also owned land in Berks County.12

Peter and Elizabeth had nine children, born between 1733 and 1752. He recorded their births in the family Bible, inherited from his father Hendrick. Interestingly, Peter wrote in English, although his son Samuel would later write in the Bible in German.13 The children of Peter and Elizabeth married into German families like Dodderer, Haas, and Guisbert. Some of these families were German Reformed or Lutheran; Peter and Elizabeth obviously did not insist that their children marry Mennonites. The children went to the school of Herman Ache, and learned penmanship from him.

In May 1770 Peter sold a 200-acre tract to his son William, adjoining Valentine Haas and others, containing a wind mill.14 Elizabeth acknowledged receipt of the money, signing by mark. Peter may have been ailing by then, since he died on June 28, a month later.

Peter wrote his will in Sept 1765, five years before he died. He named his wife Elizabeth and all nine children. In the typical pattern, he left the property to the youngest son. Since Samuel was not yet of age, Elizabeth would keep the farm until Samuel was 21. After Samuel came of age he was to have the plantation, but Elizabeth was to have the privilege of living in two of the rooms, with half the garden, plus £24 per year. Samuel had to make yearly payments to the estate, to cover payments made to his brothers. William got the plantation that John was living in on Perkiomen Creek, making payments for it. John got 247 acres in Berks County. The four daughters each got £150. Sons Henry and Jacob each got a sum of £100, not to paid until nine years after Peter’s death. Whatever household goods Elizabeth did not want were to be sold, “except the waggon shall be left for the use of the plantation between my son Samuel and his mother.” Elizabeth and William were the executors.

Peter died on June 28, 1770, and the inventory of the estate was taken on July 24, 1770. It included many household goods, the standard possessions of a wealthy farmer, including a clock, rifle, cup instrument and lamp, thirteen swarms of bees, a fox trap, fish net, a map of Pennsylvania and a map of Philadelphia, the plantation on the east side of Perkiomen Creek and another one on the north side (each worth £900), a plantation in Berks County valued at £713, and three more small tracts of land. The total was over £4230. Elizabeth and William duly filed their account. After the bills were paid and goods given to her, there was a balance of £1407 to be disposed of, not including the three large plantations.

Elizabeth lived with Samuel and Hannah, as the will stipulated. She had a paralytic stroke in September 1793, as Samuel noted in the Bible, and died on August 11, 1796. She is buried with Peter at Lower Skippack Mennonite Cemetery. Samuel is also buried there with his wife Hannah.15

Four of the sons of Peter and Elizabeth and at least three of the daughters moved away. Did the sons scatter because of cheaper land elsewhere? Oddly enough, none of Peter’s numerous grandsons were named for him. There were at least six granddaughters named Elizabeth, so it could not have been a lack of naming tradition.

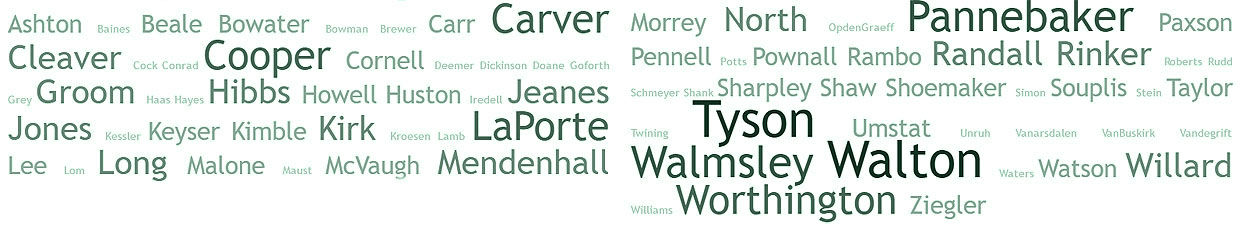

Children of Peter and Elizabeth:16

John, b. 11 Feb 1733, d. 1805 or 1806, a farmer, miller and innkeeper, m. Magdalena Porter, moved to Brecknock, Berks County. They had children Daniel, Susanna, Elizabeth, Hannah

Henry, b. July 1736, moved to Maryland17

Jacob, b. 16 Aug 1738, m. 1765 married Christina Dodderer, daughter of Conrad and Magdalena, moved to Martinsburg, Berkeley County, Virginia. They had children Jacob, Conrad, Mary, John, Christian, Elizabeth, Sarah, Nathan, and Margaret, before Christina’s death in 1774.18

William, b. 26 Aug 1740, d. 1815, m. 1767 Anna Maria Haas19, daughter of Johan Heinrich and Elizabeth; moved to Pikeland, Chester County. William and Anna were married at the Reformed Church in Germantown. She died in November 1800, aged 53. They were buried at the Reformed Church in East Vincent Township, Chester County.20 They had children Salome, Susanna, Jonah, Elizabeth, and Jesse. Their daughter Elizabeth would grow up to marry her first cousin, William, son of Samuel and Hannah.

Margaret, b. Nov 8, 1742, d. 14 Aug 1797, m. Conrad Dodderer (1738-1831), son of Conrad and Magdalena, moved to Frederick County, Maryland; Conrad was a wealthy tanner who lived a long life. They had nine children: John, Samuel, Conrad, Benjamin, William, David, Sarah, Elizabeth, Susannah. Margaret and Conrad were buried in a private burying ground at their farm.21

Catharine, b. 8 Oct 1744, m. by 1765 Johann Valentine Haas, son of Johan Heinrich and Elizabeth. Some say Haas died in 1788 in Limerick Twp, others say 1822. He did not leave a will. They may have lived on the Perkiomen.22 Catherine may have first married a man named Nagel.23

Samuel, b. 4 Nov 1746, d. 13 Feb 1826, m. 15 May 1768 Hannah Gilbert24 (1747-1837), inherited his father’s homestead and mills.25 Samuel and Hannah were buried at the Lower Skippack Mennonite Cemetery. They had children Daniel, Benjamin, William, Jacob, Samuel, John, Joseph, Abraham.

Elizabeth, b. 4 Jan 1749, m. 1767 Johan Henry Haas at the Trappe Lutheran Church. In 1793 Henry sold his land in Skippack and Perkiomen and moved to Northumberland County, where he died before Jan 30, 1805. He did not leave a will. The children were named in a deed as Abraham, Henry, William, Sarah married to Paul Kerster, John, Valentine, Hannah married to George Boyer, Maria married to Jacob Nagle, Susanna, Elizabeth married to Frederick Moyer and Samuel.26

Barbara, b. 25 Dec 1752, m. Andrew Worman, moved to Maryland. In 1789 a tract of 248 acres called “Level Farm” was resurveyed for Andrew Worman in Frederick County. Was this the same Andrew?27 Their children may have been Sarah, Susanna, Elizabeth, John, William, and Margaret.28 Andrew may have died in 1811 in Unionville, Frederick County, Maryland.29

- The upper part of Philadelphia County was not spun off as Montgomery County until 1784. ↩

- On September 1, 1755 Sower’s Newspaper carried a notice. “Peter Panebecker of Skippack has built a fulling mill, which is in charge of an experienced fuller, William Nenny.” In Hocker, Genealogical data relating to the German settlers of Pennsylvania. ↩

- Peter’s father Hendrick was probably Reformed, but Peter’s mother Eve Umstat was from a Mennonite family. ↩

- Samuel W. Pennypacker, 1902, “Pennypacker’s Mills in Story and Song”, pamphlet. ↩

- Samuel W. Pennypacker, Genealogy of the Pennypacker Family, mss, 1880. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1902. ↩

- The page is at Pennypacker Mills; the name of the merchant is unknown. The page must have been taken out of the book before Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker acquired it. ↩

- Abstracts from the Pa. Gazette 1748-1755, p. 308 (now on Ancestry). ↩

- John B. Franz, “Franklin and the Pennsylvania Germans”, PA History, vol. 65, no. 1, 1998, available on the psu.edu website. The letter, with the names of the signees, was published in the PA Archive, Second Series, volume 2, and is available on USGWArchives. ↩

- Hans Jost Heijt was an interesting character sometimes called “the Baron of the Shenandoah”. He immigrated to New York in 1709 as a poor refugee from the Palatinate, moved to Pennsylvania by 1714 when he bought land on the Skippack, and added another 600 acres four years later. In 1730 he sold his Pennsylvania land and moved his family south to the Shenandoah Valley, where he bought 100,000 acres and lived out his days as a wealthy squire. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, Book H16, page 256. ↩

- Bean, History of Montgomery County. Samuel W. Pennypacker suggests that this may have been the Berks County property. (1902, Pennypacker’s Mills in Story and Song, 1902, pamphlet available at Pennypacker Mills). ↩

- The Bible is now at Pennypacker Mills. ↩

- Was this on the west side of Perkiomen Creek, across from the home plantation on the east side? ↩

- Cemetery records from the Umstat web site. ↩

- Samuel Pennypacker, Genealogy of the Pennypacker Family, 1880 mss. The dates are taken from Peter’s family Bible. Note that Pennypacker gave the marriage of Peter and Elizabeth as 1733, with no month specified. Apparently there is no surviving record of the date. He did give the birth of John as February 1733, so perhaps they were actually married a year earlier. A 1756 census of Perkiomen Township stated that Peter Pennypacker had eight children under 21 years. This would be all of them except John, the oldest. Peter was listed as a miller, with 500 acres, 300 unimproved, 100 clear, 25 with corn, as well as seven horses, 14 cattle, and 15 sheep. His brother Henry was also a miller in the township with 3 children under 21 and 100 acres. (Census online at a website on the history of Schwenksville) ↩

- Ancestry trees give his wife’s name as Catherine Beidler, and sons as Henry and Cornelius, with no evidence. ↩

- This list is from Ancestry trees. ↩

- Pennypacker gave it as Mary Hanse, but this is from the marriage record. (Pa. German Marriages, p. 109) ↩

- Ron Mitchell, a descendant. ↩

- Henry Dotterer, The Dotterer Family, 1903, p. 120. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1880 mss. ↩

- This was not in Pennypacker’s 1880 mss. ↩

- Pennypacker gave it as Gesbert, but it is Gilbertin in the marriage record. (Pa. German Church Records, vol. 1, p. 460) In the Pannebaker family Bible it looks like Ginsbert or Ginsbart. The Bible is now at Pennypacker Mills. ↩

- Hannah Benner Roach, Skippack Deaths, #270 and 271. ↩

- Mertz Genealogy, online, particularly well researched and documented. ↩

- List of resurveys before 1800, History of Western Maryland, vol. 1, p. 376, online at Google Books. ↩

- Pennypacker does not have information on their children; this list is from Ancestry trees. ↩

- Findagrave. There was no record there of Barbara’s burial or death. ↩