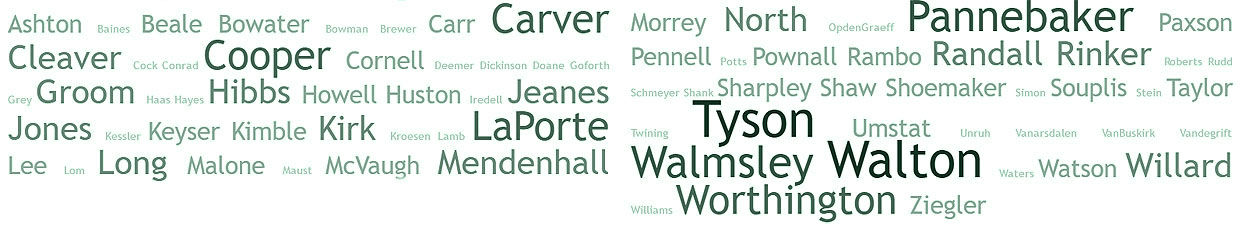

Hendrick Pannebaker, the emigrant founder of a large Pennsylvania family, has been well-documented, with a biography written by a descendant, but there are some large gaps in our understanding.1 Was he in fact born in Flomborn? Why did he emigrate? How did he make his living before he bought land in 1702? Where did he learn surveying? Some things will probably never be known about him. Yet he was a prominent man in early colonial Pennsylvania—a surveyor, landholder, writer of legal papers and deeds. His biographer Samuel W. Pennypacker called him the “patroon” of his township.2 He was known to the leaders of the colony, men like Edward Shippen, to whom he wrote a letter signed, “Jur frend”, and James Logan, who referred to Hendrick as an authority to resolve a survey question, and Thomas Fairman, possibly to William Penn.3 He feuded with the minister Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. He was acquainted with Francis Daniel Pastorius, who gave him a Lutheran Bible in Dutch, and a French grammar.4

Hendrick was born in 1674, probably in Flomborn, a small town in the Rhineland-Pfaltz, about ten miles from the Rhine River.5 When Samuel Pennypacker visited in the 1800s, it had “two main streets that cross each other, a Reformed church, an inn,… and two-story houses, roofed with tile, where farmers who till the surrounding country have their homes together, as is the German custom.”6 Some stories suggest that the family moved to Flomborn from Utrecht in the late 1500s or early 1600s, making Hendrick a man of Dutch heritage living in Germany. He may have moved to Crefelt, about 165 miles northeast along the Rhine, before he immigrated, since he referred to himself as “of Crefelt” in his family record. (It is also possible that he was actually from Crefeld, not Flomborn.)7 He wrote in German script but with some Dutch words like “het” for “the”. Muhlenberg, who knew him personally, called him “Niederdeutsch”, Low Dutch. He spoke German, Dutch, and English, probably learning English after he emigrated.8 On Dutch documents he signed as Hendrick, on German documents as Heinrich, and on English documents as Henry.

Hendrick came to Pennsylvania in 1698, arriving in Philadelphia on September 2, as he wrote in his own family record.9 He was twenty-four years old. Why did he emigrate? He was not known to be a Mennonite or Quaker, who came to escape religious persecution, although he lived in a heavily Mennonite community once he immigrated. He was probably a member of the Reformed Church and had several of his children baptized there. Like Francis Daniel Pastorius, he was literate, able to read and write, as in his family record. Did he come, like Pastorius, out of a personal desire to live in the “Holy Experiment” that was Penn’s colony. Flomborn was not far from Krisheim, where the Mennonites were severely persecuted.10 In his family record he called himself “of Crefelt”. Had he moved there with some of the Mennonites? Most of the Quaker community of Crefeld, facing persecution, had emigrated to Germantown in 1683, but there were still some Quakers and Mennonites there and in the surrounding towns.

Once he came to Pennsylvania Hendrick settled in Germantown. Like many German towns, it had a main street with close-joined houses owned by artisans and farmers. Dominated by Germans, but including English, Dutch and others, it included people of many faiths. As a visiting Dutch Reformed minister, Rudolphus Varick, wrote in 1690, “The village consists of 44 families, 28 of whom are Quakers, the other 16 of the Reformed church, among whom I spoke to those who had been received as members of the Lutheran, Mennonites and Baptists, who are very much opposed to Quakerism, and therefore lovingly meet every Sunday when a Menist Dirk Keyser from Amsterdam reads a sermon from a book by Joost Harmensen.” Since there were no Reformed churches in Pennsylvania in 1690 (or in 1698 when Pannebaker lived there), the implication was that Reformed people like Pannebaker worshipped with other groups. In fact he would spend much of his life surrounded by Mennonites, including the family of his wife.11 Once they moved north in Montgomery County, there were other German Reformed people to form a congregation.

On October 14, 1699, Hendrick married Eve Umstat, who came in 1685 with her parents John Peter and Barbara. They were probably married in Germantown; there is no record of the marriage except in Hendrick’s own notes. The first of their children was born in January 1702, the same year in which they left Germantown and moved north to Van Bebber’s township on the Skippack in northern Philadelphia County, along with Eve’s brother, and Mennonites such as Claes Jansen, Johannes Kuster, Jan Frey, and Cornelius Tyson. The township was owned by Matthias Van Bebber, son of Jacob Isaacs. Jacob Isaacs was a Mennonite baker of Crefeld who bought 1000 acres in Pennsylvania in 1683 and emigrated along with his wife and sons Matthias and Isaac. Jacob became a distiller, while Matthias bought a 6166-acre tract of land on the Skippack. In early 1702 he established a settlement there, mainly of Mennonites, and began to sell off tracts to settlers.12 A few years later Matthias moved to Bohemia Manor in Cecil County, Maryland, where his father and brother also settled.13

Hendrick and Eve continued to add to their family, and in May 1710 they had three of their children, Adolf, Martha, and Peter, baptized by the minister of the newly-formed Dutch Reformed church in Bensalem.14 Founded by ethnic Dutch who migrated to Bucks County from Staten Island and Long Island, it was the only Reformed church in the area at that time.15 It is not clear where Hendrick and Eve had their remaining five children baptized. As is typical of the time, we know little about her life, other than through the activities of her husband and their children.

Hendrick worked as a surveyor, especially between 1719 and 1733, when there were at least ten roads and townships known to be his work. He laid out roads to grist mills, to the ford on the Schuylkill, to iron works, to churches. He laid out the townships of Franconia in 1731 and the manors of Springfield, Manatawny and Perkasie in 1733. He must have been a well-known figure in the county.16 Presumably he also farmed on his land on the Skippack creek, to which he added more starting in 1708.17

His biggest land acquisition came in 1727, when he bought the remainder of the Van Bebber tract from Matthias Van Bebber. This was almost 5000 acres, an enormous holding for the time. By buying that tract Hendrick became, as Pennypacker put it, the “patroon” of the township on the Skippack, responsible for selling the remainder to settlers and for paying the quitrent.18 There may have been some resentment, since a year later Van Bebber wrote a paper proclaiming that “my desire and will is for every of you to Injoy all which I sold and Convayed unto you and No more and that ye Rest the Said Henry Pannebeckers May Injoy according his Deed… without Quarling or hinderance.”19 Pennypacker noted that this document was folded into a long narrow slip and that the back was rubbed, showing that he carried it around him to show people.

As Pennypacker put it, Hendrick had reached a position of success. “He gave of his lands to each of five sons, and they all became millers, almost the only occupation in which at that early day, in a rural community, capital could be invested at a profit. … He made surveys for the Proprietors and individuals and trained a grandson named for him, Henry Vanderslice, … to succeed him. He shipped flour to Philadelphia to the Penns. His teamster, Abraham Yungling, drove to the recently erected furnaces and forges in Philadelphia, Chester and Berks Counties … and hauled the iron, one ton at a time, to the Philadelphia merchants. …He was engaged in at least five lawsuits. He read his Bible, printed at Heidelberg in 1568, and his other books of mystical theology and what not, and generously, though unwisely, loaned of his store to his neighbors.”20

In 1728 there was an incident with the Indians, an interruption in the usually harmonious relations. An armed group of Indians forced their way into some houses in Colebrookdale and seized foodstuffs. When an armed group of settlers went after them, shots were fired and two settlers injured. The Mennonites of Skippack, pacifists and probably unarmed, petitioned the governor for aid. Hendrick Pannebaker signed as one of the petitioners, and may have written the petition. “… May ye 10th 1728. We think It fit to address your Excellency for Relief, for your Excellency must knowe That we have Suffered and is like to sufer By the Ingians, they have fell upon ye Back Inhabitors about falkners Swamp, & near Coshapopin. Therefore, we the humbel Petitioners, With our poor Wives & Children Do humbly Beg of your Excellency To Take It into Consideration and Relieve us the Petitioners hereof, Whos Lives Lies At Stake With us and our poor Wives & Children that is more to us than Life. …” Governor Gordon visited the assembled chiefs in Conestoga, bearing gifts, and mutual peace was restored.21

Hendrick knew many of the prominent people of early Pennsylvania and did surveying work for them. One of his letters to Edward Shippen has been preserved, written in February 1742.22 His spelling was creative, as he was writing in his third language. He is telling Shippen three things: that the daughters of Abraham op den Graff approve of some deed Shippen has done, that the tract of Humphrey Morris [probably Morrey] could not be divided because the instrument is out of order and William Streets could not repair it, and that the people who bought the 300 acres will pay at the May fair and the draft of their title is ready.

“Frind Edward Shippen My Keind Respek too Juw too let Ju understan tha I haffe Spoken With the totters of Abraham op then graff an by ther Words are Willing too Sings Jur deets as ther broders haffe don. As for dveiding the trak belonging too homfry Morris is not don because my Instrament Was out of order. I det send hat too Wellem Strets an hey send het horn too mey bey my Son bout I Kam too treiet het Wold Not doo an I haffe send het bak too him again. As son as I haffe att my hand again I shal fulfill the Sam. An forther I lat Ju untterstan that the peopel that haffe bought the trey Hundret ackers take all the Kar watt is in ther pouwer too pay att the May faer. therafore my deseier of Ju is that Ju may be Reade too mak them a good Lawful teittel. an I haffe madem ther draght Redey. Now mor att this pressents as mey Keind Resspeck too Ju an Jor broder. from Jur frind Henry Pannebecker”

Another glimpse of Hendrick’s personality comes from his feud with Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, founder of the Lutheran Church in America. Hendrick identified with the Reformed Church, and he “reviled” the Lutherans.23 His son-in-law Anthony Van der Sluys had sided with Muhlenberg and contributed to his church and schoolhouse, but Hendrick influenced Anthony to turn away from Muhlenberg. On his deathbed in 1752 Anthony reconciled with the pastor and asked him to preach his funeral sermon. Muhlenberg used the occasion to gloat about Anthony’s change of heart, using the funeral text, “Is not this a brand plucked out of the fire”. The family was insulted, and Hendrick warned Anthony’s children against associating with the Lutherans, pouring out “angry speeches”. Muhlenberg reported on the whole affair to his church in Germany, complacently adding, “The old man [Hendrick] has now by a sudden death been sent into eternity.”24

There is no evidence to show when Eve died.25 She probably died before Hendrick, leaving him to go live with one of his children, since the inventory of his household goods (taken at his death) was scant. He died in early 1754 in Providence township. The inventory of his goods included apparel, books, bedding, a table and coffee pot, and bonds, for a total of 194 pounds two shillings.26 The last record of Hendrick shows his generosity. On June 16, 1754, in Sower’s Newspaper, Hendrick’s son and son-in-law took out an ad: “Henrich Pannebecker died recently, aged 81 years. Many books had been borrowed from him. Those who have these books are asked to return them to Peter Pannebecker or Cornelius Theiszen.”27

Martha, b. 12 Jan 1702, bp. May 1710, d. 1761, m. 1725 Anthony Van der Sluys, lived in ProvidenceTownship; he d. 1752, named five children in his will: Henry, Ann, Catherine, Eva, and Anthony. Anthony was a miller.

Catherine, b. 8 June 1704, no further record unless she is identical with Susanna (see below)

Oliffe, b. 14 Feb 1707, bp. May 1710, d. ab. 1787, lived in Limerick Township, m. Susan LNU , eight children named in his will: Martha, Henry, Mary, John, Catherine, Eva, Elizabeth, Lydia.29 He was a miller like his brothers.

Peter, b. 8 March 1710, bp. May 1710, d. 1770, m. 1733 Elizabeth Keyser, daughter of Peter and Margaret30. He built a fulling mill on the Perkiomen Creek, served as an assessor for Philadelphia County, had children: John, Henry, Jacob, William, Margaret, Catherine, Samuel, Elizabeth, and Barbara. Peter and Elizabeth are buried at Lower Skippack Mennonite Cemetery.

John, b. 27 Aug 1713, d. 1784 in Providence Township, m. Annetje Keyser, daughter of Peter and Margaret. Like his brothers he was a miller. They had children Dirck, Henry, Margaret, Elizabeth, Jacob, Catherine, Hannah, Samuel.31

Barbara, b. 28 June 1716, d. possibly 1792, m. in 1738 Cornelius Tyson, son of Matthias and Barbara. They lived in Perkiomen Township and had children including Matthias, Henry, John, William, Cornelius.

Jacob, b. 5 March 1719, d. 1752, m. Margaret Tyson, daughter of Matthias and Barbara, lived on the Skippack Creek.32 They had six children, all in Jacob’s will except Jacob: Matthias, Cornelius, Henry, Elizabeth, Barbara, Jacob.

Henry, b. 26 Sept 1725, d. 1792, m. Rebecca Kuster, dau. of Hermanus and Sibilla, lived in Upper Salford Township, where he owned a fulling mill. They had seven children: Harmon, John, Benjamin, Sibilla, Magdalena, Henry, Jacob. Henry was a member of the Mennonite Church of the Skippack.33

Some Keyser genealogies show another daughter, Susanna, who married Peter Dirck Keyser, and lived in Worcester Township, Montgomery County. Peter was born in 1705, the son of Peter Dirck and Margaret. This is an inference and probably incorrect, based on Peter Keyser calling John Pennebacker his brother-in-law in his will. John was married to Anneke Keyser, Peter’s sister, so that is where the relation came from. The last name of Susanna is not known. 34

- Some information, like the handwritten family record shown here, became available after Pennypacker’s biography was written in 1894. It was a short note that Hendrick wrote on the first page of a book by Jacob Bril. The text and facsimile were published in the Pennypacker Express, March-April 2008, on the website of the Pannebakker Family Association. This is material that Samuel W. Pennypacker did not know; it was discovered later and is now held in the library of Pennypacker Mills. ↩

- Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker, “Bebber’s Township and the Dutch Patroons”, PA Magazine of History & Biography, 1907, vol. 31. ↩

- Samuel W. Pennypacker, Hendrick Pannebecker, Surveyor for the Penns, 1894. Fairman wrote on a resurvey, “This is the tree I suppose wch Pannebecker shew’d me in obr 1725 mark’d W.P.” The implication is that Pannebecker ran the line between the manors of Williamstadt and Gilberts, possibly in the presence of Penn himself. ↩

- Marion D. Learned, Life of Francis Daniel Pastorius, 1908, pp. 280-281, in a list of books in Pastorius’ library. Pennypacker (1907) thought that Hendrick may have inherited Pastorious’ personal seal. ↩

- All the writings about him agree that he was born there, based on Pennypacker’s assurance, but in his own family record he called himself “of Crefelt”. Pennypacker is the source for Flomborn as the birthplace, as he put it, “according to evidence which I think is convincing” (1894, p. 19). We would like to see his evidence. Nothing is known for certain of Hendrick’s parents, possible siblings, or relation to other emigrants with the Pannebaker name such as Friedrich or Weiant. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1894. ↩

- Carl Klase, curator at Pennypacker Mills, agrees with the idea that Hendrick may have moved to Crefelt before coming to Pennsylvania. It is also possible that Governor Pennypacker was wrong, and that Hendrick was from Crefelt instead of Flomborn. ↩

- According to Pennypacker, he typically wrote his name “Hendrick Pannebecker”, using “Henry” later in life when associating with the English. ↩

- Hendrick’s note in the book by Jacob Bril. Hendrick dated it, “Written this 17 Day February 1745”, long after the events, allowing for possible error. ↩

- William Hull, William Penn and the Dutch Quaker Migration to Pennsylvania, 1970, p. 398. ↩

- It is sometimes said that Johannes Umstat, Eve’s brother, was married to Mary Pannebaker, an otherwise-unknown sister of Hendrick, but there is no evidence for this. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1894. ↩

- Bohemia Manor had a colorful history. Augustine Hermann, its founder, was born in Bohemia, served in the army and supposedly fought the Swedes under Gustavus Adolphus, emigrated to New Amsterdam, traded as a merchant there, was sent to Maryland to negotiate a boundary dispute between the Dutch and Lord Baltimore, made a map of Maryland for Lord Baltimore, received as payment a tract of 30,000 acres on the Chesapeake where he lived in grand style as a lord of the manor. His son Ephraim (one of the two officials who welcomed William Penn to Pennslvania with an official gift of turf and twig) persuaded him to grant land to the Labadists, a mystical sect founded in France that lived communally and shared property. Ephraim abandoned his wife to join the sect. Augustine later turned against the Labadists and regretted his lease of land to them. A codicil to Augustine’s will appointed trustees because “my eldest Sonn Ephraim Herman . . . hath Engaged himself deeply unto the labady faction and religion, seeking to perswade and Entice his Brother Casparus and sisters to Incline thereunto alsoe, whereby itt is upon Good ground suspected that they will prove no True Executors of This my Last Will of Entailment . . . but will Endeavour to disanull and make it voide, that the said Estates may redound to the Labady Communality.” Augustine died in 1686. (References: Pennypacker, 1894; Journal of Jasper Danckaerts; Innes, New Amsterdam and its People. ↩

- They probably did not trek down to Bensalem with the children. Reverend Van Vlecq was known to preach in Skippack, as well as Germantown. Another child, Catherine, was alive at the time. Had she already been baptized, possibly because of serious illness? Carl Klase, curator at Pennypacker Mills, suggests this possibility. Christ Church, Philadelphia, would have been a possibility, but their records are not early enough. ↩

- With names like Kroesen, Cornell, Vandegrift, Vanartsdalen, Van Horn, and Lefferts, the Dutch formed a distinct ethnic community, intermarrying, speaking Dutch, prospering as farmers. In 1710 they formed a church under the leadership of Reverend Paulus Van Vlecq. He served the church in Bensalem and also preached at Germantown and Skippack. He returned to Holland in 1713, after being found guilty of bigamy, and the church ceased to exist as a Reformed congregation for over fifteen years. Ref: W. H. Davis, History of Bucks County; also “A Brief History of The Low Dutch Reformed Church in Lower Bucks County”, author unknown, no longer available on the Warminster Township website. ↩

- Henry S. Dotterer, Perkiomen Region, 1895. In 1734 Nicholas Scull submitted a bill to the proprietaries requesting over £50 in payment for surveys, £40 of which was to be paid to Hendrick Pannebaker. ↩

- Theodore Bean, History of Montgomery County, 1884. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1907. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1907. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1907. ↩

- Pennypacker, 1907. ↩

- The original letter is in the Shippen papers at the PA Historical Society. Shippen was a member of the “Pennsylvania elite”, a wealthy businessman and lawyer. Shippensburg is named for the family. ↩

- As Muhlenberg wrote in his Journals, “his father-in-law, who was a drunkard and a slanderer of our church and practice, never ceased to express to his son-in-law his hatred and contempt for the office…” ↩

- Pennypacker, 1894. ↩

- Dates given for her death range from 1739 to 1764, since there is no known gravestone for her (or Hendrick). ↩

- Philadelphia County estate papers. There was no will, just the inventory and a bond given by his administrators Peter Pannebaker (son) and Michael Sickler of Skippack, tanner. ↩

- Hocker, Genealogical data relating to the German settlers of Pennsylvania and adjoining territories. ↩

- From Hendrick’s family Bible, later passed down to his son Peter, now in the library at Pennypacker Mills. Also in Samuel W. Pennypacker, Genealogy of the Pennypacker Family, 1880 mss, on Ancestry. ↩

- The name of his wife as Susan is from a deed in 1754 from Adolph Pennepacker and his wife Susan to Nicholas Schwenk in 1756 for 154 acres. Some sources say he married Agnes Miller, with no evidence. ↩

- His tombstone says he was born in 1712. This is from Hendrick’s family record. ↩

- He left no will. The estate papers (administration, inventory, account) are on Ancestry, PA Wills & Probate Records. ↩

- This is the line of Samuel W. Pennypacker. ↩

- Their children are traced on the website at pennypacker.net, called “Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker’s hand-written papers”. ↩

- Peter and Susanna were not known to have children named Henry or Eve, which would have settled the matter. ↩