Peter Larsson Cock and Margaret Lom were early settlers in New Sweden, and founders of a large family. Peter was born at Bångsta, Turinge parish, in 1610. In 1641 he was sent to New Sweden as a punishment. Many of the early colonists had been convicted of minor crimes such as poaching; we do not know what Peter did to deserve being deported. It could not have been too serious, since he apparently received payment of 2 dalers for food and clothing. Peter got his surname from serving as a cook on the Charitas on the voyage.

In 1643 he married Margaret Lom, one of the seven daughters of Måns Lom and his wife Anna Petersdotter. Margaret and her family had also come over on the Charitas, on the same trip. Peter and Margaret lived on two islands at the mouth of the Schuykill, later known as Fisher’s Island and Carpenter’s Island. His plantation there was called “Kipha”. A farmer, like almost all of the Swedes, he became relatively prosperous by the standards of the time.

He served on the court of justice under the Swedes, Dutch, and English. He was a magistrate under Dutch rule, a justice under the English, and a councillor under the Duke of York.

In 1653 Governor Johan Printz accused Peter of illegally selling guns to the Indians. A jury found him innocent, but Printz nevertheless sentenced him to three months of hard labor. This was one of the grievances of the freemen against Printz in the protest of 1653. His name does not appear in the dramatic events of 1655 when the Dutch fleet arrived from New Amsterdam to take over the colony, led by Peter Stuyvesant. As a law-abiding and loyal Swede, he must have been in the fort with the other adult men, ready to fight if necessary. Margaret would have been at home with four small children under ten years. In the end the Swedes capitulated, the Dutch sailed away, and life continued as usual, except that Peter was now a magistrate for the Dutch court.

The Dutch allowed the Swedes to keep their property and hold their court. But in 1658, Stuyvesant grew concerned about reports of fraud and smuggling. He visited the South River himself to meet with the magistrates including Peter Cock, Peter Rambo and Olof Stille. Stuyvesant appointed a vice-director to watch over the business of the Dutch West India Company; this probably made little difference to the law-abiding farmers. In 1664 the Dutch themselves were ousted from the colony, when the English took over. In the South River this was a formality. The Swedes again kept their property, but now they were under the rule of the Duke of York and his appointed governors. Peter Cock was still on the court, now a justice.

In the fall of 1669 Peter was deeply involved in an insurrection of the Swedes against the English; however he took the side of the English, as did most of the more prosperous Swedes. A man appeared in the colony and claimed to be a member of the noble Konigsmark family. He went among the Swedes and Finns and made speeches urging them to throw off the rule of the English. Peter Cock played a part in the downfall of this rebel.

“A large proportion of the Swedish colonists let themselves be persuaded, and concealed the alleged Konigsmark in the Colony a long time, that no one might learn about his presence. They carried the best food and drink they had to him, so that he lived exceedingly well, and what is more, they went to Philadelphia and bought powder, bullets, lead, etc .to be ready at the first signal. He had the Swedes called together to a supper, and after the drinks had been passed he exhorted them to throw off the old rule, reminded them of what they had suffered, and finally asked them whether they sympathized with the King of Sweden or the King of England. A few declared themselves at for the Swedish ruler, but Peter Kock pointed out that since the land was English and the settlement had been duly ceded to the English crown he ought to support the English sovereign. Thereupon he ran out, slammed the door, and braced himself in front of it so that the alleged Konigsmark could not get away, and called for help to arrest him. The imposter tried to force open the door, and Kock stabbed his hand with a knife; though the swindler got away [temporarily]. But Kock reported the matter to the English, who out and made the alleged Konigsmark a prisoner. Captain Kock then demanded his real name, for, he said, “We can see that you are not of noble blood.” He then admitted that his name was Marcus Jacobson. He was so ignorant that he could neither read nor write. After being branded, he was sold in the Barbados as a slave. The Swedes who had sided with him lost half of what they own – land, cattle, clothes and other goods.”

The next crisis in which Peter played a part was two years later, in the fall of 1671, when there was talk of war against the Indians, in reprisal for the murder of two Dutch men on Matiniconck Island. A Council met at Peter’s house to decide on their position. Peter Cock, Peter Rambo and the other magistrates decided that war was inevitable, “there must upon necessity a warr in the spring”, but that it should not be started until then. William Tom, the high sheriff, wrote the letter laying out their reasons.”

“The Result And Reasons Of The Magistrates Of Delaware Against Declaring War Against The Indian Murderers. … The Indyans not bringing in the Murtherers according to their promise I went up with Mr Aldrichs to Pieter Cocks and there called the Raedt (Council) together to informe your honor what wee thinke most for or preservacon and defence of the river.

First wee thinke that att this time of the yeare itt is to late to begin a warr against the Indyans, the hay for our beasts not being to be brought to any place of safety and so for want of hay wee must see them starve before our faces: the next yeare we can cutt it more convenient.

2nd our corne not being thrashed or ground wee must starve for want of provisions which this winter we can grind and lay up in places of safety.

3rd that there must upon necessity a warr in the spring and by that time we shall make so much as we can preparacon but wayte from yr honor assistance of men ammunition and salt.

4thly wee intend to make Townes att Passayuncke, Tinnaconck, Upland, Verdrieties Hoocke, whereto the outplantacons must retire.

5thly we thinke that your honor’s advice for a frontier about Mattinacunck Island is very good and likewise another at Wicaquake for the defence whereof your honor must send men.”

It was signed by Peter Cock and Peter Rambo, both by mark, and others.

This crisis blew over and there was no war the next spring. However relations with the Indians were always tinged with fear. In 1675 there were rumors that the Indians had killed two Englishmen and Governor Andros called a conference between the magistrates and the Indians to calm the situation. They met on May 13, 1675 at New Castle, with Israel Helm, Lasse Cock, Peter Cock, and Peter Rambo among the group of English. The Indians were a group of four sachems from both sides of the Delaware. The governor assured them, with Israel Helm translating, of his desire for friendship and thanked them for coming. The first sachem stood up and took notice of his old acquaintances Peter Cock and Peter Rambo. He presented a large belt of wampum to the governor, who reciprocated with gifts of four coats. The calm approach of Andros defused the situation.

Peter Cock stayed on the court, as it met in Upland (present-day Chester). In April 1678, in a typical meeting, the court met at his house. They paid out money to Peter Rambo for the court’s accommodations (probably food). They paid a bounty for wolves’ heads brought in. They paid the salary of Sheriff Cantwell, and heard actions of debt over money not paid for tobacco and corn and wheat and oxen. After the Quakers arrived in 1682 and 1683, the Swedes were very helpful to them, in selling food, translating between the English and the Swedes, acting as intermediaries with the Indians. In one meeting, in June 1683, several Indian sachems sold the land later to be Byberry and Moreland to Penn. They exchanged the land “between Pemmapecka and Nesheminck Creek” for “Wampum,…guns, shoes, stockings, Looking-glasses, Blankets and other goods, as ye said William Penn shall be pleased to give unto us.” Lasse and Peter Cock were both witnesses.

Peter Cock served William Penn in another way, one that was critical for the province. When Penn’s commissioners needed to buy land to lay out the city of Philadelphia, the Swanson family and Peter Cock owned the bulk of the land they needed. “The Commissioners had power from Penn, in case they found the site they might pitch upon already occupied, to use their best endeavors to persuade the occupants to give up their claim. They accordingly offered Cock and the Swansons larger tracts of land elsewhere in lieu of their present possessions. The plan was entirely successful.” The Swansons were granted a tract of 600 acres and Peter Cock got 200 acres, both laid out north of the city in the Liberties.

By now Peter Cock was an old man, in the last few years of his life. He almost disappears from the public records, as his son Lasse followed him as a magistrate and leader among the Swedes. We only see one more glimpse of Peter and it is not a happy one, rather an event that must have been traumatic for his family.

In October 1685, Peter and his daughter Bridget sued John Rambo for breach of promise and for ruining Bridget’s reputation. The court testimony was sensational. Bridget’s sister Catherine said that one winter night she heard a noise about midnight, and a plank opened and John Rambo jumped down into the room and then came into the bed where she was with her two sisters. It was pitch dark but they recognized him by his voice. He jumped into the bed. There was no room so Catherine and Margaret got out of the bed and left Bridget there, and they lay on the floor until daybreak. John asked Bridgett if she would have him. She answered no at first and then when he asked her again she said yes. He swore “the devil take him if he would not marry her”. And in the morning he heaved himself out of the bed and left.

A friend testified that when Andrew Rambo was married to Peter Cock’s other daughter, he heard John Rambo, between the dwelling house and cow house, about midnight, say to Bridgett Cock, “God damme me my brother hath gott one sister and I will marrie tother.” Lasse Cock, Bridget’s brother, deposed that about the end of February last, his sister Bridget went to the mill with corn, and they saw John Rambo. Bridget said, “John Rambo you are going to cheat me”, and he answered “God damme me I shall never marrie another woman but you.” The jury found Rambo guilty. Bridget’s father Peter was fined five shillings for swearing in court.

But it did not work out quite as smoothly as that. A year later they were back in court. In the meantime Bridget had borne a child, which John refused to maintain, and he was trying to marry another woman. Bridget sued him for 150 pounds damages. He claimed that he never offered to marry her. She produced the records of the earlier court. It would seem a cut-and-dry case in her favor. But Lawrence Hiddings, a neighbor of the Cock family in Kingsessing, testified that Bridget had refused to let John have the child when he offered to maintain it, she saying that it was more than he was able to do and that he did not have a nurse ready. The jury found for him. But in the end John decided to marry Bridget. They went on to have eleven children, and moved to Gloucester County, New Jersey, where he served on the Assembly and on the Court.

In 1693 Lars Cock, oldest son of Peter and Margaret, wrote a letter to his uncle Måns in Stockholm. It has been preserved and almost serves as an obituary for Peter.

“… In the first place, what pertains to my late father: He came out here to the country of New Sweden, sent by his Royal Majesty to settle the land with the others, his countrymen; which he also did honorably for the high authorities. My late father was selected as a president [justice] in New Sweden which he did with the greatest loyalty; and during the Holland Dutch regime he was also a president on the court; and in the English regime’s time likewise. My late father was always in advice and counsel with them. My late father, after he had been in this country one year and a half, gave himself into the state of holy matrimony and had with his dear wife thirteen children whereof now, God be praised, six sons and six daughters are living, all well provided for with wives and husbands, so that of all my late father’s lineage in the first degree, that is children and grandchildren, there are living seventy-one souls; and in the year 1687, the 10th of November, my dear father fell asleep, in the name of the Lord, at a good age, leaving after him my dear mother… If my uncle Mouns Larsson is dead, or the other brothers of my father, then I hope that their children or grandchildren may be alive, that I may receive a gladdening answer to this my letter. They lived at Bängsta hamlet in Södermanland. My father’s father’s name was Lars Persson. He lived at the same hamlet. Now … praying that you direct your letter to Gothenburg to His Royal Majesty’s Postmaster, Johan Thelin, and he shall certainly have it delivered. And we live at Passayongh on the Delaware River in Pennsylvania. Commending you together with our whole family to the almighty, and under his gracious protection, and will ever be found your most obedient, Lars Persson Cock

P.S. When you write a reply to me, write to me thus, “Lars Persson Cock”. Since we were living here among foreign nations, my late father took that surname so that we and others could be distinguished from one another.

Dated and written at Pennsylvania on Delaware River, the 31st of May 1693.”

Peter wrote his will in June 1687. He wrote it at his island plantation, which he called Kipha. He left all his estate to his wife Margaret, and after her death to his twelve children, six daughters and six sons. All the children were to share equally, except that Gabriel was to have the island and £30 in consideration of his care for Peter and Margaret. The island of Kipha was to be kept, if possible, in the family forever. He signed it with his mark. All six of his sons witnessed it: Lasse, Eric, Mounce, John, Peter, and Gabriel, in addition to two sons-in-law, Gunnar Rambo and Robert Longshore. Peter died on November 10, 1687, but the will was not proved until the next March.

The inventory of the estate was taken in March 1688/9 by two of the sons, and showed substantial wealth for the time. In addition to his great coat, two pairs of breeches and five shirts, Peter and Margaret owned five beds with their bolsters and pillows, brass hanging candles and candlesticks, pewter porrigers, pots and plates, funnels, bottles, pots, farm implements like cow bells and plow irons, a large copper still, tubs, forms, boards, dripping pan, Bible, large German book, steers, young oxen, young bulls, hogs and sows, ewes and lambs. The total value came to almost £200, not counting the value of the plantation, which was another £255.

After he died Margaret probably stayed in the house, as Peter wished, although all of her children were married by about 1691. She outlived Peter by about fifteen years. She did not leave a will; administration was granted to her son Gabriel on February 13, 1702/03. The inventory was taken the same week. The substantial list of goods suggests a comfortable life. She owned four feather beds, pillows, bolsters, coverlets, blankets, sheets, table cloths, pillow cases, towels, a looking glass, butter churn, pestle and mortar, candlesticks, iron kettles and pots, brass kettles, iron, yearlings, horses, sheep, swine.

It is not known whether Peter and Margaret are buried on their island or at Gloria Dei.

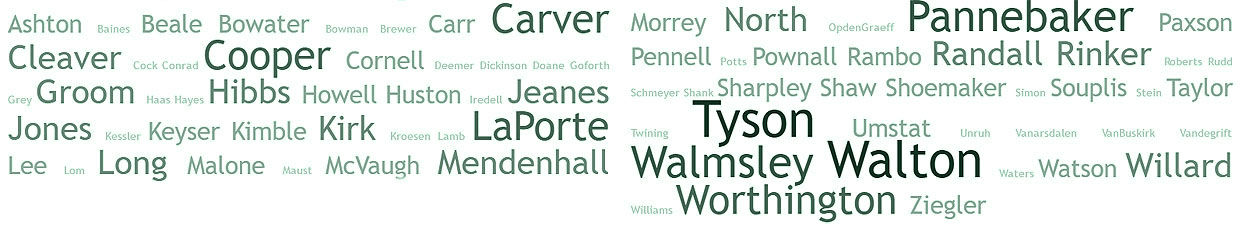

Their children intermarried with other prominent families such as Rambo and Helm.

Children of Peter and Margaret:

Lars (Lasse), b. 1646, d. 1699, m. Martha Ashman in 1669. Lars, known as Lasse or Lassey, was a prominent figure in the early records. He served as an interpreter for sales of land from the Indians, and on court cases involving Swedes. In 1682 he took a message from the Swedes to Penn that they would serve him as good citizens. He interpreted in 1683 for the witchcraft trial of Margaret Mattson before the Provincial Council. He was elected to the Assembly in 1681. In 1677 he was one of a group of Swedes who petitioned Governor Andros for land in present-day Bucks County where they could lay out a town and settle together. This was denied because the land had not yet been purchased from the Indians. Instead Lasse and Martha settled at Passyunk, where he died in October 1699. He wrote a will, naming his wife Martha and children Peter, John, Andreas, Catherine, Robert, Mouns, Lawrence, Gabriel, Margaret, and Deborah. Martha was still living in 1724.

Eric, b. ab. 1650, d. 1701, m. Elizabeth, daughter of Olof Philipsson (a Finn), moved to Gloucester County, New Jersey, where he died in 1701. Elizabeth died in 1735. Children: Peter, John, Lars, Olof, Helena, Margaret, Anna, Maria, Eric.

Anna, b. about 1652, d. before 1722, m. Gunnar Rambo, son of Peter and Britta, moved to Upper Merion on the Schuylkill. Anna died before Gunnar. He died in 1724. Children: John, Peter, Gunnar, Anders, Måns, Brigitta, Gabriel, Matthias, Elias.

Måns, b. ab. 1654, d. after 1720, m. Gunilla, daughter of Jonas Nilsson. Måns was an Indian trader. By 1697 they moved to Senamensing, Burlington County, then to Gloucester County. They were in frequent litigation in the Burlington Court. In 1705 he was found guilty of shooting the horse of Elias Toy and fined £10. In 1720 he pledged money for the church at Raccoon Creek. Children: Margaret, Peter, Jonas, Helena, Gabriel, Maria, Catherine.

John, b. 1656, d. 1713, m. Brigitta, daughter of Nils Larsson Frände. They lived in Passyunk until 1700, then moved to St. George’s Creek, New Castle County. He died in 1713; she was still alive in 1720. Children: Peter, Catherine, Charles, Magnus, Anna, Maria, John, Augustine, Elias. In 1685 John admitted to stealing a sow from Harman op den Graeff and was fined £9 plus costs of suit.

Peter, b. 1658, d. 1708, m. Helena, daughter of Israel Helm. He was a church warden of Gloria Dei. They lived in Passyunk where he died in 1708. Children: Maria, Helena, Peter, Margaret, Israel, Måns, Catherine, Deborah, Susannah.

Magdalena, b. 1659, d. after 1723, m. Anders Petersson Longacre in 1681. Anders inherited his father’s farm at Syamensing. Children: Peter, Anders, Margaret, Helena, Maria, Catherine, Gabriel, Anna, Magdalena, Britta. He died in 1718; Magdalena was still alive in 1722.

Maria, b. 1661, d. after 1717, m. Anders Rambo, son of Peter and Britta. They lived in Passyunk, where he died in 1698. Maria was still living in 1717. Children: John, Anders, Peter, Brigitta, Maria, Martha.

Gabriel, b. 1663, d. after 1714, m. Maria, daughter of Nils Larsson Frände. Gabriel inherited the island from his parents, but sold it in 1714 and moved his family to St. George’s Creek, New Castle County, to live with the family of Maria’s widowed sister Brigitta. Children: Peter, Gabriel, Rebecca, Margaret, David, Anna, Ephraim, possibly two others.

Brigitta, b. 1665, d. 1726, m. John Rambo, son of Peter and Britta. Brigitta and John had a tempestuous courtship. John climbed into the garret of the Cock family house around December 1684 and stayed with Brigitta all night. She became pregnant and took him to court, twice, before he finally married her around 1686. They moved to Gloucester County, to land from John’s father. John served on the Gloucester County Court and on the West Jersey Assembly. Brigitta died in 1726; he died in 1741. Children: Brigitta, Catherine, Margaret, John, Peter, Maria, Elisabeth, Anders, Gabriel, Martha, Deborah.

Margaret, b. 1667, d. 1701, m. 1) Robert Longshore probably in 1687, 2) Thomas Jenner in 1696. Robert Longshore was an Englishman, a deputy surveyor for Penn. He and Margaret had two children, Euclid and Alice, before Robert died in the spring of 1695. The next year Margaret married Thomas Jenner, a carpenter and another Englishman. They had a daughter Maria. He died before October 1701, when Margaret wrote her will, dying soon after. She left her land in Kingsessing to Euclid.

Catherine, b. 1669, d. 1748, m. Bengt Bengtsson. He was active at Gloria Dei for years. He died in Moyamensing by 1748. Children: Daniel, Peter, Jacob, Maria.