Richard Morrey was baptized in February 1675, in London, the son of Humphrey and Ann Morrey. He was baptized at the church of St. Bartholomew the Great in Smithfield. His parents would later become Quakers.1 He was the youngest of their known children and only one of two to survive to adulthood.2 He first came to New York as a child with his parents before 1683, then moved to Philadelphia with them. His father Humphrey was a successful merchant, and Richard may have gone back to England to be educated. About 1695 he married a woman named Ann, whose last name is unknown.3 There are no records of Richard Morrey in Pennsylvania until 1702, when he witnessed a deed of sale by his father Humphrey of a Philadelphia city lot.4 Was he acting as the English agent for his father’s trading business until then? The family owned a house in Tower Hill, London, where Richard and Ann could have lived. In 1708 the neighborhood had “many good new buildings, mostly inhabited by gentry and merchants.”5

By 1716 Richard and Ann were living in Cheltenham, when Richard inherited considerable land from his father Humphrey, sharing some of it with his cousin, the younger Humphrey.6 They shared the Cheltenham estate of at least 450 acres and another 400 acres in Gloucester County, West Jersey. Richard got a Philadelphia lot, probably the one on Mulberry Street, while Humphrey received the “water lot”, probably the Chestnut Street property.

Richard and Humphrey probated the will of the elder Humphrey in May 1716, and the next month they began to sell his land. In June 1716 they confirmed a deed of a lot on Mulberry Street sold by the elder Humphrey but never conveyed; they confirmed the sale to Richard Hill, a Philadelphia merchant.7 In October 1716, Richard sold part of his city lot to Sven Warner, cordwainer of Philadelphia, conveying the rest to Richard’s son Thomas.8 In 1717 Richard and his cousin Humphrey made a large land purchase of their own, buying rights to 2,000 acres to be laid out from the three daughters of Nathaniel Bromley, a First Purchaser of land from Penn.9 Two years later, in 1719, Richard, his wife Ann, and cousin Humphrey sold a lot in the city to Joseph Taylor, a Philadelphia brewer.10 It was the city lot that went along with the Bromley purchase.11 The next year the Morreys sold another lot from the Bromley purchase to William Branson, joyner, and in 1721 they sold yet another part of the lot to Hugh Cordry, pulley maker.12 In 1722 Richard and Humphrey partitioned the 2000 acres of the Bromley land, laid out in Wrightstown, Bucks County.13

In May of 1720 Richard and Ann Morrey made an unusual transaction that reveals something about their marriage and possibly Ann’s birth family.14 Thomas Turner of London had conveyed a credit from the stock of the East India company to Richard Morrey, supposedly in a will written on May 11, 1711. He conveyed one-third of a credit worth £325, a handsome bequest.15 What was Morrey’s relation to Turner? Given the terms of the 1720 conveyance, it is possible that Turner was Ann Morrey’s father. The money was clearly intended for Ann’s use. Richard and Ann conveyed the one-third part to Job Goodson and John Warder of Philadelphia, who were to invest the money for the use of Ann Morrey. Her husband was not to meddle with it, and it would be excluded from his estate. Ann was to dispose of the profits “at her own will and pleasure”. This unusual provision suggested that the profits were to be Ann’s because they came from her father.

Who was Thomas Turner of London? He was certainly well-off, possibly a merchant. According to the 1720 deed, he wrote his will on May 11, 1711. There was a Thomas Turner of St. Botolph, Aldersgate, London who wrote his will on May 11, 1711, but he named no family in the will except a cousin, left most of his money to charity and the poor, and did not name any stock credits.16 Other men named Thomas Turner died around 1714 to 1715, but did not name Richard Morrey in their wills, and none of them signed their wills in 1711.17 The Thomas Turner who made the bequest must remain unidentified for now.

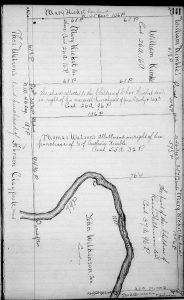

In 1726 Richard bought 1,000 acres from Nathaniel Roberts of Kent County, England, for £30.18 This purchase may have overextended Richard’s funds, since in August 1729 he was in financial trouble. He turned again to Job Goodson, John Warder, and Samuel Preston, and set up a trust to cover his debts.19 He conveyed to them his house and 250 acres in Cheltenham, his land in Gloucester County, a house and lot on Front Street in the city, and several lots on Chestnut Street, including the rents.20 The properties were granted to the three trustees for a term of 60 years, they paying one peppercorn to Richard Morrey each year if it was demanded.21 From the income of the properties, the trustees were to pay Morrey’s debts, make a payment to Ann for her maintenance and that of their son Thomas, and pay a smaller amount to Richard for his “pocket expenses”.22 Richard also transferred to the trustees the 984 acres laid out for him on Manahatawny Creek in Philadelphia County with the intention that they should sell it. The question arises: why did Richard go through this complex deed instead of selling the some of the properties himself? It is possible that he could not find ready buyers or that his creditors were pressing for immediate payment. Richard may have been living beyond his means. In various records he is described as a gentleman, suggesting that he lived off the income from the rents of the city lots, and perhaps any profits from his rural land. This may not have been enough.

Richard may have been trying to speculate in real estate because his sister-in-law, brother-in-law, and nephew had been successful at it. Richard’s brother John, about nine years older than Richard, married Sarah Budd in 1689 under the auspices of Philadelphia Monthly Meeting.23 Sarah was the daughter of Thomas and Susanna Budd, wealthy Quakers who owned property in West Jersey and Philadelphia.24 After John and Sarah were married, he worked as a merchant. In early 1692 he requested two trees from the proprietor’s land to build a crane on his wharf.25 John died at a young age, in 1698, leaving Sarah with three young children, only one of whom would like to adulthood.26 After John’s death, Sarah began to buy and sell land with her brother John Budd and son Humphrey (after 1718 when he came of age). At one time or another she owned a share of land in Chester County, rights to 3000 acres in Philadelphia County, and land in West Jersey.27 Her son Humphrey would be even more successful as a land speculator (and as a distiller). With his uncle John Budd, Humphrey owned rights to 5000 acres to be laid out in Pennsylvania.28 When he died in 1735, Humphrey left legacies of over £1400, plus his extensive real estate holdings.29

In 1735, Richard lost three members of his family. The first to die was his nephew Humphrey, who made his will on 6 August and died about a week later. He left large sums of money to his cousins on the Budd side (his mother was Sarah Budd), and left his uncle Richard and cousin Thomas each £20 per year.30 The second loss was that of Jane Laurence, who probably died in late September. Jane wrote a will remembering Richard and Ann, their son Thomas, their daughter Matilda Kimble and three of her children, as well as Richard’s “Negro woman Mooney”.31 The inclusion of Mooney, also known as Cremona, strongly suggests that Jane was a member of Richard’s household.32 Some of the wealthier families of Philadelphia included an unmarried lady in their household, who helped manage the servants and the children.33 Jane Laurence must have filled this role for the Morreys for many years. Humphrey Sr. had named her in his will in 1716. She was a lady; her inventory included some silver spoons and a silk gown.34 She was obviously capable. In 1708 the administration of the estate of Richard Sutton, collar maker, was granted to her after his widow renounced. This was at a time when women were rarely administrators unless they were the widow. The final death in 1735 was Richard’s son Thomas. He made his will in September and died in late October.35 The fact that Jane and Thomas died so soon after Humphrey suggests that they were victims of an infectious disease. This was a time when malaria, smallpox, measles, pneumonia and other diseases could sweep through a community, especially in the summer months.36

Thomas’ will revealed some of his life and that of his family.37 He left to his father Richard any books he wanted. He left his mother Ann the rents of a house at Tower Hill, London, to be given after the death of his parents to cousins in Cheshire. He left 200 acres on Neshaminy Creek in Bucks County to his sister Matilda Kimbal and an adjoining 200 acres to her children. He left his microscopes to Christopher Witt, and money to his father’s servants and Negroes. He left £2 to the minister of St. Thomas Church at Whitemarsh to preach the funeral sermon. The picture is of an unmarried Anglican gentleman living a comfortable life with his books and scientific devices, fond of his family and generous to his servants. Christopher Witt was an especially interesting acquaintance for Thomas. He worked as a physician, cast horoscopes, and was a friend of the botanist John Bartram.38 His library in Germantown was filled with books on philosophy, “natural magic”, and divining. Perhaps he used Thomas’ microscopes to study the plants from Bartram’s garden.

By 1745 Richard’s finances were apparently mended, since he was able to make two generous gifts.39 The first was to his kinsman Leonard Morrey formerly of Buerton, Cheshire. Richard and Ann sold 700 acres in Cheltenham to Leonard for 5 shillings, a nominal sum to make it a legal contract.40 The land adjoined Richard’s other Cheltenham land.41

The other gift that Richard made that winter was unique in the early history of Pennsylvania. Richard had been involved in a long-time relationship with his Negro slave Cremona, known to the family as Mooney. It is not clear whether it was consensual on her part or whether his wife condoned the relationship. But the relationship produced five children and ended only when Richard freed Cremona. It is hard to believe that his wives, Ann and later Sarah, would not have known about it. In January 1746 Richard gave Cremona a tract of 198 acres in Cheltenham adjoining the land of Isaac and Rynear Tyson. She was to pay a rent of one peppercorn per year, but the land was hers and her heirs, “in consideration of the good and faithful service unto him done and performed”.42 This liaison, between an older man and his dependent slave, is unsavory, but at least he freed her in the end and made her financially independent. She did not marry for eight years, until after Richard’s death, suggesting that she had an emotional bond to him.43 By January 1754, she was married to John Frey, a freed slave. In 1772, after Cremona died, the land was put in trust for Cremona’s children, the five with Richard Morrey, and Joseph, the son with John Frey.44 A difference had arisen after Frey’s death and the family chose this way to settle it.45 The trustee was the Quaker farmer Isaac Knight of Abington. John and the children conveyed the land to Knight for 30s, to be held in trust until John Frey’s death, at which time Knight was to sell it for the benefit of the six children.

Ann Morrey died some time between 1735 and 1746. Administration on her estate was granted to her husband Richard.46 For some reason there is no record of the administration in Philadelphia, but it was noted in England, probably because the family still held property in London.47 She had made a will and left a legacy to Abington Monthly Meeting. The minutes of the meeting noted the legacy, “I give and bequeath unto Abington Monthly Meeting the sum of 5 pounds, the Which legacy this mtg is given to understand is in the hands of Henery Vanaken of Phila, wherefore James Paul our Treasurer is appointed to receive the said legacy of the said Friend and place it to the common stock of this mtg and to give a receipt in the name and behalf of this mtg for the same.”48

In June 1746 Richard married Sarah Allen, a widow, at Trinity Church in Oxford. Richard had been raised as a Quaker, but at some point he had fallen away. He does not appear in the records of Abington Meeting or Philadelphia Meeting. Sarah’s background is unclear, although much has been speculated about her. Her brother was John Beasley; he served as the executor of Richard’s estate.49 When she married Richard, she was the widow of an Allen.50

In 1752 Richard and Sarah went to court to solve a problem. His father Humphrey had left Richard the Philadelphia lots with their valuable yearly quitrents, but they were entailed in the male line. That is, Richard owned them but could not sell them; they could only be passed down to his male heirs. That must have seemed feasible in 1716 when Humphrey died, but after 1735, when both Thomas and his cousin Humphrey died, there were no male heirs in the Morrey line. Richard and Sarah went to the Court of Common Pleas for a common recovery, an elaborate legal fiction which circumvented the terms of the bequest. This involved a token sale of the property, a “straw man” who appeared in court briefly then disappeared, and a judgment from the court that the actual owner should recover the land in fee simple, with the right to sell, instead of fee tail.51 Now Richard and Sarah were free to sell the rents, and in January 1753 they sold them to Israel Pemberton for £550, a large sum.52 Pemberton, a wealthy merchant and philanthropist, was sometimes called the “King of the Quakers” for his wealth, power and influence.53 On August 1753, Richard and Sarah sold a lot “on the Northern Bounds of the said city” to William Chancellor for £500, as well as a property in Cheltenham.54

Finally, in August 1753, Richard Morrey made his will, after a long and eventful life. He was 78 years old, and outlived his first wife and his only son. He left all his property to his wife Sarah, and made her and her brother John Beasley the executors, with William Chancellor and Jenkin Jones as overseers.55 He died not long after. Joshua Harmer, a Quaker neighbor, was asked to be a bearer at the funeral. He refused, saying that there were younger men more fit for the purpose, but the sexton gave him a pair of gloves anyway, as was the custom for bearers at an Anglican funeral. Joshua was reported to Abington Monthly Meeting for taking the gloves against the rules of the Society of Friends, and he had to make acknowledgment of the fault.56

The inventory of Richard’s estate was taken on February 11, 1754. By then Sarah Morrey was also dead, her brother John Beasley acted as the surviving executor. The inventory shows the level of comfort that Richard and Sarah had enjoyed. In their main house, in northern Philadelphia, they had walnut leather chairs, prints on the walls, a clock and looking glass, a Delft punchbowl, a mahogany oval table, spice box, and ample linens.57 In addition, they still had a simple home in Cheltenham, sparsely furnished. After their deaths, the house was offered for sale in an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette: “House where Richard Murray, dec’d, formerly dwelt, near the northern bound of Phila., bounded on W. by ground of George Royal and on E. by land of Jonathan Zane, for sale; apply to William Chancellor in Market St. (2 May 1754)58

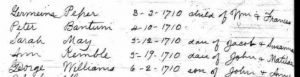

Children of Richard and Ann:59

Matilda, m. Anthony Kimble about 1715. Nothing is known of Anthony’s background. He is not named in any Quaker records. They lived in Bucks County, where Anthony died before 1735. Matilda married again, possibly twice.60 She died in 1749 or 1750. Children of Anthony and Matilda: Mary, Ann, Rosa, Anthony, William.61

Thomas, born about 1698, died 1735 unmarried. He was a gentleman, who probably lived with his parents. He left a will, naming his sister and her children, as well as his parents. He left fifty pounds to St. Thomas (Episcopal) Church in Whitemarsh on condition that they maintain his tomb for “all times hereafter”. He requested that a brick tomb be built over his grave with a stone over it and six evergreen trees to be cut and trimmed in good order.

Richard and Cremona had five children. Robert used the surname Lewis; the others used Murray.

Children of Richard and Cremona:62

Robert, b. ab. 1735; apprenticed to a shoemaker, possibly neighbor Reynier Tyson63

Caesar, b. ab. 1737; apprenticed to a shoemaker

Elizabeth, b. ab. 1739. She was a maid for Nicholas and Sarah Waln; they wrote a letter of testimony for her in 4th month 1773.64 Elizabeth later married Cyrus Bustill, a prosperous black businessman and founder of a school for black children. It is said that Cyrus donated bread for Washington and his troops, and that Bustleton is named for him. Elizabeth and Cyrus lived as Quakers but were unable to join as members because of their race. One of the descendants of Cyrus and Elizabeth was Paul Robeson, the actor and singer.

Rachel, b. ab. 1742, m. Andrew Hickey

Cremona, b. ab. 1745, m. 1766 John Montier, had four sons.

- Baptismal records of St. Bartholomew, online on Ancestry, London, England, Church of England Baptisms marriages and burials 1538-1812, City of London, St Bartholomew the Great 1653-1672, image 72. ↩

- He was about nine years younger than his brother John. ↩

- No marriage records have been found for Richard and Ann in Pennsylvania. They could not have been married much after 1695, since their daughter Matilda was married with a daughter Mary by 1716 when Richard’s father Humphrey named Mary in his will. (Even if “Mary” was a copyist’s error for Matilda, then Matilda must have been born no later than 1698 or so.) It is possible that Ann was the daughter of Thomas Turner of London; see the discussion below. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book F8, p. 264. ↩

- Walter Thornbury, Old and New London, 1881, p. 95, on Google Books. ↩

- Will of Humphrey Morrey, Philadelphia County wills, Book D, p. 11-12. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book F1, p. 37. It was a tripartite deed. Humphrey and Morrey signed, along with Samuel Corker, to whom the land had been sold (but not conveyed). ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book E7-v10, p. 195. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book F6, p. 132. Bromley was a soap maker of London; he did not come to Pennsylvania. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book F3, p. 39. ↩

- First Purchasers were entitled to a city lot and land in the Northern Liberties as a bonus when they bought rights to land in the countryside. Although Nathaniel Bromley’s country land had not been laid out, the city lot was laid out on Front Street. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book H20, p. 423; Book H 16, p. 510. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book F6, p. 148. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book G8, p. 295. Although written in 21 May 1720, the deed was not delivered and recorded until 1746. ↩

- Because of the importance of this bequest to the Morreys, it is likely that they owned a copy of Turner’s will; this would have been their source for the date. The deed specifically said that it was a bequest, not an indenture or deed of gift. ↩

- The text of this will is on Ancestry.co.uk, England and Wales: Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills 1384-1858, Prob. 11, 1713-1722, Pieces 545, image 319-320. The gift was known as Thomas Turner’s Charity. In a record in the Parliamentary Papers: 1850-1908, vol. 71, p. 180 (on Google Books), the Commissioners examined the state of the charity in 1832. The record stated that Turner was buried at the churchyard of the parish church in Walthamstow, not in St Botolph’s. Findagrave has a record of a burial of Thomas Turner at St Mary’s, Walthamstow, on March 11, 1711 (two months before the date when the Aldersgate man was supposed to have written his will). It is not clear whether these are the same man or two different ones, but neither one can be made to fit with the bequest to Richard Morrey. Could this Thomas Turner have conveyed the stock to Richard Morrey as a deed, not in his will? It is possible; a search on Ancestry.co.uk did not produce any relevant deeds. ↩

- These included a glazier of London (wrote his will on August 3, 1715, with daughters Elizabeth and Mary); a vitualler of Middlesex (wrote his will on April 15, 1714, wife Joan and son William); the president of Christ Church College (wrote his will on April 29, 1714, many bequests, mostly to the college). (Records on Ancestry.co.uk for all three) A prominent Quaker and traveling missionary, Thomas Turner of Coggeshall, Essex, wrote his will on January 20, 1710, leaving property to his wife Ann, naming no children, with bequests to the Quakers. He mentioned no stock credits. His will was probated in January 1718/19. (Essex Archives Online, document D/ACW 25/82, by subscription) He is probably the cordwinder who married Ann Meaken of Coggeshall at the Quaker meeting there in 1685. He may be the Thomas Turner of Coggeshall who traveled to America in 1697 and again in 1704 as a Quaker missionary. The voyage in 1697 was in company with Thomas Chalkley, described in Chalkley’s Journal. A Hannah Turner, daughter of the Quaker Thomas Turner of Coggeshall, died in 1705 at the age of 19. (Piety Promoted in Brief Memorials…, by John Tomkins, vol. 2, 2nd ed, 1789, p. 69, on Google Books) ↩

- Minutes of the Board of Property, Book I, p. 741. In December 1726, Richard requested that 500 acres of the purchase be laid out. (Copied Survey Books, D69, p. 23, on the website of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission) ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, book F2, pp. 515-521. ↩

- It is not clear what property Richard still owned after this conveyance. ↩

- This nominal payment was adopted to make a valid contract, even though the conveyance was basically one-sided. ↩

- There was no mention in the deed of Richard’s daughter Matilda. Since she was married by then, the assumption was that she was no longer maintained by her parents. ↩

- They declared their intentions of marriage on 29th 1st month 1689. (Minutes of Philadelphia Monthly Meeting) ↩

- Some give Sarah’s parents as John Budd and Rebecca Baynton; this would make her too young to marry in 1689. In addition, the will of Humphrey Morrey in 1735, son of John and Sarah, named many of his Budd relatives as “cousin” or “aunt”, thus placing him (and his mother Sarah) precisely in the Budd family. Some researchers might not believe that Sarah was Thomas’ daughter, since she was not named in his will, proved in 1698 in Philadelphia (Book A, p. 384). He named his two unmarried daughters in the will. Sarah and her sister Susanna had probably already received a portion from him when they married. Besides his large landholdings in West Jersey, Thomas Budd owned the Blue Anchor Inn in Philadelphia and a block of houses on Front Street known as Budd’s Long Row. (John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia, 1857, vol. 1). ↩

- Minutes of the Board of Property, 8 Jan 1691-92. ↩

- John and Sarah had five other children who died in infancy, within a five-year period from 1695 to 1700. (William Hudson’s list of burials of non-Friends, on Ancestry, US Quaker Records 1681-1935, Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Births & burials 1686-1807, starting p. 412.) Even the wealthier families could be shaken by childhood mortality. ↩

- Minutes of the Board of Property, 12 1st month 1715/16; Philadelphia County deeds, Book I-3, p. 292; West Jersey Deed Records 4 Nov 1717. In the last deed she was described as a widow and distiller. She also kept a shop; the inventory of her estate included weights and measures, sugar, candy, pepper and allspice. She died intestate in 1720. Administration on her estate was granted to her son Humphrey. (Philadelphia County estate files, 1720, #43, City Hall, Philadelphia) ↩

- They bought the rights in 1718 from William Bacon, a gentleman of London, for £110. (Philadelphia County Deeds, Book F5, p. 401) ↩

- His will was proved in Philadelphia, Book E, p. 344. Some of his land was offered for sale by his executors William Allen and Edward Shippen, advertised in the PA Gazette, 9 Oct 1735. Humphrey was an honored member of the Philadelphia elite. In 1733, when he was elected Grand Master of the Masonic Lodge, a banquet was held at the Tun Tavern, attended by the Proprietor, Governor, Mayor and other dignitaries. (Leo Lemay, Benjamin Franklin: A documentary history, formerly online) Franklin was the Grand Master the following year. ↩

- This was to be paid out of the rents on the city lot and the Cheltenham property, which had been bequeathed by Humphrey Morrey Sr. and shared between Richard and Humphrey Jr. Once again the question arises, if these properties produced that much income, how did Richard go deeply into debt? (Philadelphia County wills, book E, p. 344) ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book E, p. 346. ↩

- The wording of the will makes it clear that she was not a relative. She left several bequests to her sister’s family in South Wales. ↩

- Elizabeth Drinker’s unmarried sister Mary lived with Henry and Elizabeth Drinker and managed the household in Philadelphia when the family was away at their summer home in Frankford. Henry once remarked that he had “two wives”. (Karen Wulf, Not all wives, 2000) ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book E, p. 346. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book E, p. 347. It is poignant to see the three wills on adjoining pages in the copy book. ↩

- Isaac Norris wrote to James Logan in 6th month 1711, “It is a very sickly season. Many are dead, and die daily.” (Penn-Logan Correspondence, v. 2) Peter Kalm, the Swedish traveler, noted in his journal that in 1728 there was an epidemic of pleurisy (pneumonia) among the Swedes at Penn’s Neck. (Peter Kalm, Travels in North America, various editions). An examination of the deaths in Gwynedd, Montgomery County, showed a peak in 5th and 6th months in 1745 when many children died. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, book E, p. 347. ↩

- S. F. Hotchkin, Ancient and Modern Germantown, 1889, pp. 176-179; Stephanie Graumann Wolf, Urban Village, 1976, p. 276. Witt died in 1765 at an old age and was buried at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Germantown. ↩

- In addition, in 1744 Richard conveyed 40 acres in Bucks County to John Bewley and Ann his wife. Ann was one of Richard’s granddaughters. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book G7, p. 261. Leonard had bought land from Richard’s daughter Matilda the year before. (Deed Mathilda Carty to Leonard Murray and Joseph Nast, 1744, private collection of Edward R. Kirk, Private Mss in Bucks County, vol. 1, 1828) Matilda married a man named Carty after her husband Anthony Kimble died. ↩

- Leonard mortgaged the property to George Okill and Robert Greenway in November 1746. Philadelphia County deeds, Book H10, p. 297; Book H14, p. 557. The 1757 mortgage spells out the family relationships, naming Leonard Morrey as “the only son and heir at law of John Morrey deceased who was the only son of Leonard Morrey deceased who was the only brother of the said Humphrey Morrey the elder deceased.” In other words, Leonard was the son of Richard’s first cousin John, and one of the cousins in Cheshire to whom Thomas left the rents of the London house after the deaths of Richard and Ann. In 1761 some of this land was sold in a sheriff’s sale. (Philadelphia Deeds, Book H14, p. 557) ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book G7, p. 539. ↩

- Some researchers, such as Doctor William Pickens III, have called the relationship an interracial love story. (“The Montiers: An American Story”, documentary on WHYY, 2018.) Unfortunately, we have nothing in Cremona’s words to tell us how she felt. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book D21, pp. 501-3. The deed was signed on 23 January 1772, but not recorded until 1788. The story of Cremona’s children is told by Reginald Pitts, in “Robert Lewis of Guineatown”, Old York Road Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 51, and “The Montier Family of Guineatown”, OYRHSB, vol. 41. ↩

- Interestingly, the deed referred to Richard Morrey’s intention that the land should go to his children with Cremona, but “by the Second Marriage of the said Cremona that intention was in some measure defeated.” This implies that Richard and Cremona were married, for which there is no evidence. ↩

- She left a will, which he apparently did not probate. The administration was not granted until some years after her death. ↩

- Lothrop Withington, “American Gleanings in England”, PA Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 28. A search for Ann’s will in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury did not find any results. ↩

- Minutes of Abington Monthly Meeting, 30 10th month 1751. ↩

- The name is spelled in many ways: Bazeley, Bazold, etc. ↩

- Some have described her as the granddaughter of the baronet Sir James Morgan of Llantarnam, but Stewart Baldwin does not support a connection between the baronet and the Pennsylvania Morgans, and does not include a Sarah Beasley in the family at all. (Stewart Baldwin, “Edward Morgan of Gwynedd, PA”, online at http://sbaldw.home.mindspring.com/e_morgan.htm, accessed March 2020.) ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book H4, p. 65; Wikipedia entry for Common Recovery. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book H3, p. 532. The twelve rents totaled £53.8 per year. ↩

- In addition to being in the Assembly, Pemberton was also the clerk of the Yearly Meeting of Friends. ↩

- Philadelphia County deeds, Book H4, p. 59. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book, K, p. 141. The will is rather short and mentions no grandchildren or daughter Matilda. It did say that he was “indisposed” when he wrote it. ↩

- Minutes of Abington Monthly Meeting, 7th month 1754, 10th month 1754; 12th month 1754. Quaker preferred simple funeral ceremonies without formalities such as giving away rings or gloves to the pallbearers. (J. William Frost, The Quaker Family in Colonial America, 1973, p. 43) ↩

- Philadelphia County estates, City Hall, 1754. The appraised value of his property was £232, not including his real estate. ↩

- Abstracts from the PA Gazette 1748-1755. This seems to be the same property they had sold to Chancellor the preceding August. Did he allow them to continue living in it until they died? ↩

- No birth records have been found for them. Matilda is firmly placed in this family. Thomas named her in his will, and her daughter Mary referred to Richard as her “dear grandfather”. Matilda must have been born no later than 1695 in order to have a married daughter by 1716, when Mary Hicks was named in the will of Humphrey Sr. ↩

- Bucks County Orphan’s Court Record #113. ↩

- Rose or Rosa is a common name in the Budd family, but the Budds were distant cousins for Matilda. Why did Matilda not name a son for her father Richard? ↩

- Reginald Pitts, “Robert Lewis of Guineatown”, Old York Road Historical Society Bulletin, 1991, vol. LI; “The Montier Family of Guineatown”, OYRHSB, 1993, vol. LIII. ↩

- Pitts, “Robert Lewis of Guineatown…” ↩

- Anna Bustill Smith, “The Bustill Family”, Journal of Negro History, 1925, vol. 10(4), pp. 638-644, available on JSTOR. She seems to have originated the idea that Elizabeth’s mother was an American Indian named Satterthwaite, without any evidence. This has been widely repeated. ↩