William Hibbs the Quaker was supposedly born in Gloucestershire, England, around 1665. Many sources claim that he was the son of William and Joan, from Dean Forest, but there is no evidence for this, and the name is a common one.1 William emigrated on the Kent in 1677 as a young man. It is sometimes said that he was a cabin boy on the Kent. He more likely came over as a servant, like so many others who lacked money to pay their passage. The Kent carried colonists to Burlington, West New Jersey; it loaded in London and sailed in May 1677. This was a well-known voyage, as it was one of the earliest to bring Quakers to the New World. As the story goes, “King Charles the second, in his barge, pleasuring on the Thames, came along side, seeing a great many passengers, and informed whence they were bound, asked if they were all quakers, and gave them his blessing.” 2 They landed first in New York, then sailed up the Delaware to West Jersey, where most of the passengers got off. They stayed at first with the Swedes, who had thin settlements on both sides of the Delaware, then began to build their own houses.

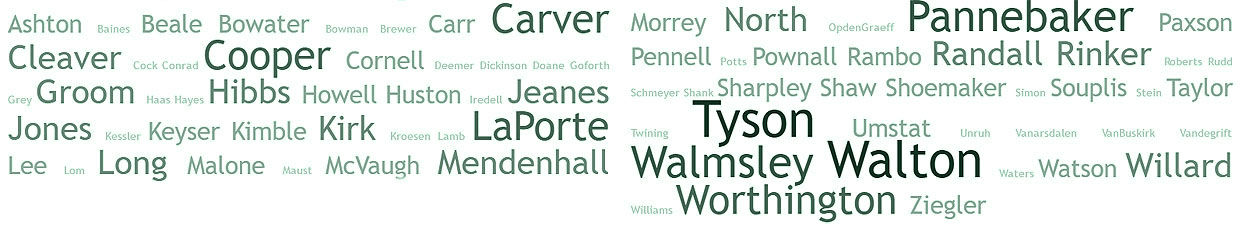

The first definite record of William in Pennsylvania is his marriage to Hannah Howell. In 10th month 1686 they accomplished their marriage at the house of John Hart in Byberry. Those present who signed their wedding certificate included Hannah’s father Thomas and brother Job, neighbors like John and William Carver, members of Byberry meeting like William Walton and John Rush.3

In 1692, when many Quakers split off from the main group to follow George Keith, Hibbs remained with the traditional meeting. He signed a paper that was sent to Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, denouncing the “spirit of separation” of Keith and his followers.4 Even so William’s relations with Byberry Meeting could be strained. In 1698 William was reprimanded by the meeting for his “disorderly behaviour in keeping on his hat when William Walton was at prayer in their meeting.” This showed great disrespect for Walton’s ministry. At the next meeting Hibbs promised to do so no more.5 The early Friends were stern with those who did not follow their code of behavior. As one historian put it, “It is fair to say that this part of Pennsylvania, from Germantown…to Byberry…to the headwaters of the Pennypack and the Little Neshaminy above Horsham, was guided and policed for 25 years by the weighty Friends of Abington Monthly Meeting.”6

William also got into trouble for his actions outside of the meeting. In 1708 Abington Meeting reported on a problem between him and Thomas Harding. “A complaint was made today against William Hibbs for detaining £3 being part of pay for a horse bought of Thomas Harding, by William Hibbs, ye matter being heard and considered, The result of this meeting is that William Hibbs do within a month pay the said Thomas Harding in Silver Money, and likewise Condemn his abusive language to Thomas Harding.”7

In 1701 William contested the boundary between his land and that of the brothers William and John Carver. When John tried to get a patent for his land in Byberry, Hibbs filed a caveat with the Secretary of the land office. At the hearing of the case, he claimed that the Carvers had taken away a corner post and thereby altered the boundaries. The Surveyor General pointed out that he himself had done the survey “to the utmost of his Power”, so that a resurvey would be futile. In the end the patent was granted to Carver.8

William died in 1709. His will, made in 1708, named his wife Hannah and eight children, Joseph, Jonathan, Jacob, William, Jeremiah, Sarah, Phebe and Hannah.9 He left a Negro man to his wife, and after her death to his sons Joseph and Jonathan, if the man was still alive then. Hannah and Joseph were to share the plantation. Each of the other children was to receive £20 when he or she turned 24 years of age. Hannah was specifically allowed to raise the children at her discretion. “I leave the whole charge of bringing up my children to my dear wife she doing this according to her own discretion.” But friends Daniel and William Walton were chosen as overseers to assist Hannah in managing her affairs. William apparently trusted Hannah with the family affairs, but not the financial ones.

Even after William’s death Hannah continued a feud he had begun with his Carver neighbors eight years before over the precise location of the property boundary. Abington Meeting minutes reported that “Whereas there hath been a former difference between John Carver and Widdow Hibbs, about a former line between them; The meeting being willing to put an end to ye sd difference: have appointed Six friends, with two Surveyors to view ye land and ye lines and to endeavor to put an end to ye differ.”10

In 1712 Hannah married Henry English at Byberry Meeting. He was a widower, a Quaker, and a resident of Byberry. They had no children together. Before they were married, Henry gave her 124 acres “in consideration of the love and good will and affection which he had and did bear towards his loving friend Hannah Hibbs.”11

Hannah died in 1737. In her will, made as Hannah English, she named her children Sarah, Phebe, Jeremiah, Joseph and William, as well as two namesake granddaughters. She gave her sidesaddle to her granddaughter Hannah Cooper and her “pilers” (pillows) to her granddaughter Hannah Hibbs. She left her clothing to daughters Sarah and Phebe (the brown gown and petticoat and riding hood and bonnet), her bed and bolster and bedding to Phebe, and residue of property to sons Joseph and William and son-in-law Jonathan Cooper. She specified that her Negro servant Trail should be set free, to have his own mare and scythe and ox, and enough wool to make him a coat and waistcoat and britches.12

The children of William and Hannah generally stayed in Bucks County, married, and left descendants. Some of them are sparsely documented, and some of the numerous people named Hibbs in Bucks County in the 1700s cannot be placed in the family.

Children of William and Hannah:

Joseph, b. 1687, d. 1762, m. 1) 1711 Rachel –, 2) 1749 Catherine Love, widow of Andrew Love. The name of Joseph’s first wife is often given as Rachel Waring, with no evidence. The children of Joseph and Rachel are not definitely known, since their birth was not recorded in Quaker records. Rachel died before 1749, when Joseph married Catherine Love at Buckingham Meeting. Soon after, he acknowledged “misconduct” with her before the marriage. He died in early 1762. He did not leave a will, and letters of administration were granted to Catherine, along with Isaac Kirk and James Spicer.13

Jonathan, b. 1689, m. Elizabeth –. The name of his wife is given as Elizabeth in a record of Abington Monthly Meeting; her last name is not given.14 The names of their children are also not known.15 In 4th month 1716 Abington Meeting issued a paper of condemnation against Jonathan Hibbs and his wife.16 In 6th month 1717 Jonathan wrote another paper condemning his outgoing with his wife.17 The paper was accepted. This may have been in an attempt at rejoining the meeting. Was he the Jonathan Hibbs buried in Philadelphia in June 1722 as a non-Friend?18

Sarah, b. 1692, m. 1714 Jonathan Cooper. Jonathan was not from the Cooper family of Philadelphia. He immigrated in 1699 with his parents from Yorkshire and settled in Buckingham.19 Wrightstown Meeting recorded the death of Jonathan Cooper the elder in 2nd month 1769 at the age of 98.20 Children: Hannah, William, Sarah and others.

Phebe, b. 1697, m. 1715 Paul Blaker at Abington Meeting. He was the son of Johannes Bleikers, one of the original thirteen settlers of Germantown in 1683. Bleickers was the only one of the original thirteen to move away from Germantown and settle in Bucks County. The names of children of Phebe and Paul, if any, are unknown.

Jacob, b. 1699, m. 1727 Elizabeth Johnson with a license from New Jersey. In 1723 Jacob was living in Byberry, where he took out a mortgage for his land adjoining his brother Joseph.21 Jacob is supposedly buried in the Johnson-Williamson Cemetery in Bensalem. Jacob and Elizabeth do not appear in Quaker records. Children: Jonathan, Jacob and Phebe.22

William, b. 1700, d. 1789, m. 1728 Ann Carter at Middletown Meeting.23 In order to marry Ann at Middletown Meeting, William brought a certificate from Abington Meeting.24 They had twelve children, including Hannah, who married James Cooper, son of William and Mary.25 Hannah and James were the grandparents of James Fenimore Cooper.26

Hannah, b. 1702, died young.

Jeremiah, b. ab. 1707, m. 1735 Hannah Jones, daughter of John and Margaret, at the First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia.27 John Jones was wealthy.28 Jeremiah did not manage his money well, according to a petition by his sister Sarah and her husband Jonathan Cooper to the Bucks County Orphans Court.29 Jeremiah and Hannah had a daughter Hannah, named in the petition. He did not leave a will in Bucks County.

- Many web trees and message boards repeat this information. Martha Grundy has a thoughtful discussion on her website, online as of March 2019 at https://sites.rootsweb.com/~paxson/balderston/Hibbs.html. ↩

- Samuel Smith, History of Colony of Nova-Caesaria or New-Jersey, excerpts on the web. ↩

- Abington Monthly Meeting, Marriages 1685-1721, online on Ancestry, US Quaker Meeting Records 1681-1935, Montgomery County, image 13. All the Quaker records in this account can be found on Ancestry. ↩

- Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, Minutes 1679-1703, image 170. It was probably sent from the Quarterly Meeting. Others who signed the paper included Thomas Groom, Thomas Howell, William and Daniel Walton, Giles Knight and Henry English. ↩

- Minutes of Philadelphia MM, cited in Isaac Comly, “Sketches of the History of Byberry”, Memoirs of the HSP, vol. II, 1827. ↩

- Arthur Jenkins, “The significance of the history of Abington Meeting”, Old York Road Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 1, 1937, p. 30. ↩

- Abington MM Minutes, 7th month 1703. ↩

- Minutes of the Board of Property, series 2, Minutes Book G, 10th month 1701, formerly available on Google Books, now (2019) available on Archive.org. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, book C, p. 198. ↩

- Abington Meeting minutes, 3rd month 1709. There is no word about how the matter was settled. ↩

- Comly’s Sketches of the History of Byberry, p. 181. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, book F, p. 31. ↩

- Bucks County Probate records, file #1117. Why were none of his children named as administrators? ↩

- Various names have been suggested, with no evidence. ↩

- Some web trees give the names of the children as Elizabeth, William, Jonathan, and Eli. ↩

- Abington Monthly Meeting, minutes 1682-1746, image 47. ↩

- Abington Monthly Meeting, minutes 1682-1746, image 50. ↩

- William Hudson kept a list of burials of non-Friends, included in the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Births Deaths Burials 1688-1826, on Ancestry, image 289. ↩

- Jonathan was named in the 1709 will of his father William. ↩

- Wrightstown Monthly Meeting, Births and Deaths, image 22. He did not leave a will in Bucks County, although he had plenty of time to make one. ↩

- Abstracts of General Loan Office Mortgages, PA Genealogical Magazine, vol. 6, p. 270. ↩

- Margaret Johnson of Bristol died in 1751. In her will she named Jonathan, Jacob and Phebe Hibbs, children of her daughter Elizabeth. ↩

- In contrast with some of his siblings, William’s marriage, death and children are well documented. His death and age at death were recorded in the records of Henry Tomlinson (in Byberry Monthly Meeting, Deaths 1736-1823). ↩

- Middletown Monthly Meeting, Minutes 1698-1824, on Ancestry, image 86. ↩

- Three other children—Sarah, James, and Mahlon—married into the Blaker family. ↩

- The Cooper Genealogy, at jfcoopersociety.org (accessed February 2019) ↩

- They were married on Christmas. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, book G5, p. 14. ↩

- Orphans Court Record #152, Vol. A1, p. 169, online on Family Search, Bucks County Orphans Court records 1683-1776, image 105. ↩

Is there any information about the lineage of Alfred Hibbs, who was wounded and declared missing in action on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg?

I’m sorry. I don’t follow the Hibbs line that far. It was a large family, and not well documented, so you will have your hands full.