Thomas Walmsley was born in Waddington, Lancashire, the son of Thomas Walmsley and Elizabeth Rudd. His parents were Quakers. By 1682, when they made the decision to leave Lancashire for Pennsylvania, Thomas and Elizabeth had six children, including a son Thomas. They immigrated on the Lamb, which was infected with disease. Most of the adults and children survived, but the Walmsley family was hard-hit, losing daughters Margaret and Rosamund and probably also Mary. Some of those who did survive the voyage were ill when they arrived. This was probably the case with Thomas, since he died of dysentery within a month after they arrived.

The younger Thomas grew up in Bensalem with his mother and stepfather John Purslow, brother Henry and younger sister Elizabeth. In 1698 he and Mary Paxson announced their intention to marry.1 This was an advantageous marriage for him. She was the daughter of William Paxson, a member of the Assembly, active in local government, and prominent in the Middletown meeting. Thomas and Mary moved to Byberry, Philadelphia County, about 1703 and settled down to run their farm and raise a family. In addition to farming he was also successful as a dealer in horses. Thomas was not active in the meeting or the government, in contrast to his father-in-law. He did buy several tracts of land, including 400 acres in Buckingham which was so far back in the woods that he traded it for a smaller tract with his nephew William Carver Jr.2 By the time he died Thomas owned a large tract in Byberry, 200 acres in Middletown, land in Buckingham, another 60 acres in Byberry, and a farm in Moreland.3

Mary was subject to seizures. Her great-grandson John Comly remembered a story about her. “Mary had fits, many years before she died, took all her senses away, once fell in the fire, had to mind her carefully as a child. After a while she would come to…”4 Thomas and Mary went on to have nine children who lived to marry. There were gaps between the births of their children, and they may have lost at least two more. They raised the children in a one-story wood house with three rooms, built at different times, probably added to as the family grew.5

Thomas was “a quiet, peaceable man, attending to his private business; and doing but little in the affairs of either Church or State.” He was considered wealthy, and his property consisted principally of lands and horses. He was also generous. “He had good natural abilities, and although successful in accumulating property, was not at all parsimonious. As a proof of this, having a number of daughters, most of whom were married in meeting, he made provision to entertain large numbers of wedding guests, sometimes amounting to more than a hundred; and on one occasion after meeting broke up, he invited the whole congregation to dine with him.”6

Thomas Jr, eldest son of Thomas and Mary, was killed as a newlywed when he was thrown off his horse. This left seven daughters and only one son to carry on the family name (along with some first cousins). The surviving son, William, was favored in Thomas’ will, written in early 1750, when Thomas was in his late 70’s. He died four years later, in 10th month 1754. Mary died the following year.7

Thomas used his will to provide for Mary as a widow and to divide his estate among his surviving children.8 She was to have the full use and benefit of the plantation while she remained a widow, not just the use of a room or two as was often the case. In addition she was to have three horses, three cows, ten sheep and six swine, a generous bequest. After her death the plantation was to go to the son William, along with the tract in Middletown. William also received the bonds and book debts, worth over £1278, out of which he had to pay legacies of £600, to be shared among five of his sisters. (Mary and Abigail got land instead of cash.) The two youngest daughters, Esther and Martha, were unmarried at the time. They were to share a tract of land in Buckingham and the household goods not kept by his wife Mary. They also received a larger cash payment than the married daughters, who had presumably received an “outset” or dowry at the time of their marriage.

William also received the residue of the estate, and acted as executor. As Thomas put it, “Now considering my son William he having remained long in my service and proving a duty full son and considering the cumber and trouble of executing this will with divers other good considerations ingages me to conclude in manner following lastly I give and devise to my son William Walmsley and to his heirs and assigns forever all the residue and remainder of my whole estate.”9

Three of the sons-in-law were given five shillings each, a relatively token amount given the size of Thomas’ estate. It is perhaps no surprise that one of them, Isaac Carver, issued a caveat against the will. A few days afterward, Mary wrote a note to the registrar supporting the will. “I am sensible of what the contents of my late deceased husbands last will and testament is with respect to my dowry and I am therewith fully sattisfied and contented and do desire that the sd will may stand and not be frustrated nor broken by no means not withstanding any opposition made and if it was not for infirmity of body I would be glad parsonally to appear before thee to testifie my desire that my late husband Thomas Walmsleys last will may not be broken. I subscribe my self thy friend.” Five of her daughters also wrote in support, referring to Isaac as a “troublesome person.” They said, “…informed by our brother William Walmsley of .. the contents of sd will… we nothing doubting of the truth and verity of his information according to law and that notwithstanding any opposition or interruption … the same may stand in good force and not be frustrated nor broken by no means as we believe it to be our fathers will and testament. From thy friends..” This was signed by Martha Walmsley, Esther Walmsley, Abigail Walton, Elizabeth Walton , and Mary Worthington. Each signed well, showing that they had been taught to write.

It is disconcerting to see that Thomas owned slaves. Slavery was a difficult issue for early Friends, one that divided them. Some, like Benjamin Lay, John Woolman and Anthony Benezet, fought to persuade other Friends that slavery was inconsistent with Quaker beliefs. In spite of their efforts, the institution was too entrenched and too many people benefited from it. By 1754 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Friends cautiously warned against slave-holding, but it was not until 1776 that they banned it for members.10

The inventory of Thomas’ possession showed the typical goods of a well-to-do farmer of his day: his clothing and ready money, debts owed to him, household goods, livestock, corn and other grain crops, tools, and a gun, amounting to about £1560. The Negro slaves were valued at £120. Only one of them, a girl named Hannah, was specifically named in his will. The others would have been left to son William as the residual legatee. When Mary died in 1755, her inventory included only her clothing and a small legacy left to her by her father William Paxson “which she had not disposed of in her lifetime”. She must have turned the farm over to her son William.

The children of Thomas and Mary were provided for by their relatives via legacies. Elizabeth and Mary received 20 pounds each from the estate of their great-uncle Henry Paxson, who died childless in 1723 (not their uncle Henry Walmsley, who had about nine children of his own to provide for). The four oldest children got a legacy from their grandfather William Paxson. All of the daughters got a legacy from their father Thomas. Mary and Abigail got land; the others got cash.

Most of them stayed around Byberry and probably saw each other in Byberry meeting. They attended each other’s marriages. For example when Esther married Stephen Parry in 1755, the certificate was signed by her brother William, and sisters Elizabeth, Martha, and Mary.

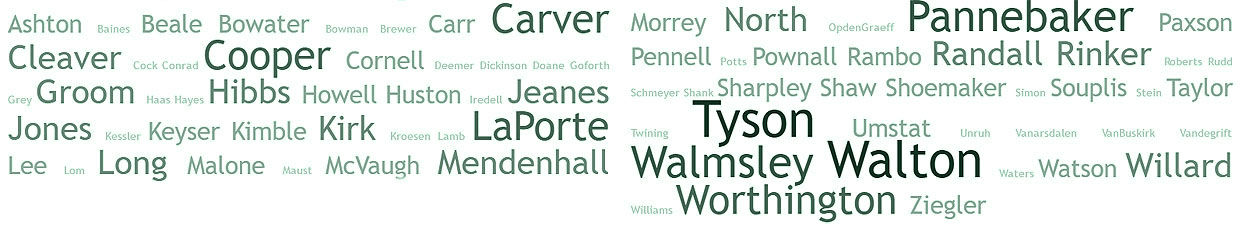

Children of Thomas and Mary:11

Elizabeth, b. 5th month 1699, d. 1787, m. 1719 at Abington Jeremiah Walton, (1694-1740), son of William and Sarah. They lived on the Byberry Road in Moreland Township. Years later, the Comly brothers recalled the family of Jeremiah and Elizabeth. “Jeremiah Walton married one of Isaac Comly’s aunts — Father of the chunky Waltons. Lived at Horsham — his wife Betty Walmsley — children well ah! – William the oldest, Tommy, Jacob, Jeremy, three girls – one married. Mary married. Sarah married Jeans, afterwards James Tyson, another Phebe remained unmarried.”12 He had a few of the names mixed up. Jeremiah died in 1740 and was buried at Horsham.13 Elizabeth lived on until 1787. Her will named five of her children, as well as several grandchildren. Children of Jeremiah Walton and Elizabeth Walmsley: William, Thomas, Rachel, Jeremiah, Jacob, James, Mary, Sarah, Elizabeth, Phebe. Seven of them lived to marry.

Mary, b. 1701, alive in October 1754, m. about 1720 John Worthington, the emigrant. His parents and origin are not known; he was probably born in England and immigrated as a child or young adult. They settled in Byberry and had eleven children, recording their births at Abington Meeting. In 1734 John was on the list of landowners in Philadelphia County with 25 acres. He made his living as a weaver.14 In 1752 John was elected as an overseer of the poor. The job was “to provide the necessaries of life to all who are unable to procure them, and not let any suffer.”15 John died in 1777. In his will he named his six living children, referred to six pieces of land, and provided for his unmarried daughter Mary, specifying that four of his sons were to build her a suitable house. Children: Elizabeth, Mary, Thomas, Hannah, John, William, Isaac, Joseph, Martha, Benjamin, Esther.

Thomas, b. 1706, d. 1728, m. 1728 at Abington Hannah Walton, daughter of William and Sarah; as a newlywed he was thrown off his horse and killed.16 Hannah died about 1741. After Thomas’ death she married Thomas Mardon in 1730 at Christ Church. Hannah’s mother Sarah named two Mardon granddaughters in her will. Children with Thomas: Richard, Rachel, Mary, Jacob, Sarah.17

William, b. 1708 or 1709, d. 1773, m. 1735 Sarah Titus at Westbury Meeting in Long Island, m. 2) 1764 at Byberry Mtg, Susannah Mason Comly, widow of Walter Comly. William became prosperous as the main heir of his parents. In the 1769 tax list of Byberry he was listed with 350 acres, by far the largest holding. He married Sarah Titus, a Friend from Westbury, Long Island, in 1735. In 1759 William noted in his account book that his wagon was used to deliver supplies to the English during the French and Indian War. It was pressed into service and brought back three months later.18 William was active in meeting affairs and often represented Byberry meeting at quarterly meetings. His wife Sarah was an elder of the meeting. She died in 1763 and William later married Susanna Comly, widow of Walter Comly. William died in 1773. Elizabeth Drinker went to his funeral and noted it in her diary for June 18: “We went to Wms house great numbers of carriages and horses there, thought it best to go to meeting before the burial, as it was very hot and dusty.” In his will William named his widow Susanna, and five children. He left three slaves – Bett, Nane, and Sam – to serve until they were 30 years old, then to be freed with a set of clothes. This was at a time when many Quakers no longer held slaves.19

Agnes, b. ab. 1710, d. ab. 1754, m. 1728 at Abington Job Walton, son of William and Sarah. He was the son of William Walton the preacher and his wife Sarah. Job attempted to preach at Byberry Meeting but was not accepted there. As Abington meeting noted in 11th month 1754 “Complaint is made by Byberry friends against Job Walton who was guilty of drinking strong liquor to excess frequently and of an unbecoming ridiculous behavior in his drunkenness as taking upon himself to preach.” John Michener and James Paul were asked to visit him and “lay the evil and inconsistency of his behavior and ridiculous conduct before him.” Agnes and Job lived in Byberry and had eight children. “He had a strong constitution and performed a great deal of hard work, yet did not get rich.”20 Agnes died in 1755. In 1757 Job married Catherine McVaugh at Swedes Church in Phila. She was probably the widow Catryna Van Pelt who married the widower John McVaugh in 1754 at the Dutch Church.21 Job died in 1784, leaving his widow Catherine and seven grown children. Children of Agnes and Job: Isaac, Sarah, Job, Isaiah, Thomas, Mary, William, Elijah.

Abigail, b. 1715, d. 1789, m. 1) 1738 at Abington MM Isaac Comly, 2) 1753 Richard Walton, son of Joseph and Esther, at Trinity Oxford Church in Philadelphia.

Phebe, b. 1723, m. 1742 at Abington Meeting Isaac Carver, son of John and Isabel. Phebe married Isaac Carver in 1742. The son of John and Isabel, he was a local character. He taught school in Byberry. Known as “Poet Carver”, he was shrewd and sarcastic in his verses about local events.22 In 1754, when Thomas Walmsley died, Isaac filed a caveat against the will. The other heirs supported the will and called him a “troublesome person”. He died in early 1787.

Esther, m. 1755 at Abington Meeting Stephen Parry, son of Thomas and Jane. Married Stephen Parry in 1755. Born in 1723, he was from a Welsh family of Radnor Township, where his father Thomas owned a grist mill near Willow Grove. Stephen died in 1763 in Moreland and left a will naming his children Martha and Jane.23

Martha, m. 1761 at Abington Meeting David Parry, son of Thomas and Jane, brother of Stephen Parry. They lived in Moreland, where Stephen left a will in 1794.24 He probably married a second wife after Martha’s death, also named Martha.25

- Middletown Monthly Meeting Minutes, 3rd month 1698 ↩

- Joseph Martindale, History of Byberry and Moreland, p. 354. The land in Buckingham went to William Carver, Jr. who was married to Elizabeth Walmsley, daughter of Henry and Mary Searle, and Thomas Walmsley’s niece. ↩

- Martindale, p. 338. ↩

- “Comly’s notes on Byberry 1680-1852”, microfilm #20436, Family History Center, probably by Joseph and Isaac Comly. ↩

- Martindale, p. 355. Much of Martindale’s information came from Joseph and Isaac Comly, brothers who were keenly interested in local history. ↩

- Martindale, revised edition, 1705, p. 355. ↩

- Henry Tomlinson’s journal of deaths, at the Pennsylvania Historical Society, and included in the records of Byberry Preparative Meeting (although Tomlinson included many non-Friends). Also in Martindale, 2nd ed. 1705, p. 189. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, 1754, #137, Book K, p. 212. ↩

- Thomas’ will was probated in Philadelphia County, 1754, 137, file K212. Mary’s estate was also probated there, 1755, 81, file G16. It included the administration letter and an inventory. There was no mention of Hannah Walton Walmsley, the widow of son Thomas. She married Thomas Mardon two years after Thomas’ accident. ↩

- Gary J. Kornblith, Slavery and Sectional Strife in the Early American Republic, 1776-1821. ↩

- Records of Middletown, Abington and Byberry Meetings; Martindale. The births of the first four children were listed in the records of Middletown Meeting. ↩

- “Comly’s notes on Byberry 1680-1852”, microfilm #20436, Family History Center, probably by Joseph and Isaac Comly. ↩

- Bean, History of Montgomery County. ↩

- Martindale. ↩

- Martindale, p. 141. ↩

- Isaac Comly, “Sketches of the history of Byberry”, Memoirs of the HSP, vol. II, 1827. ↩

- From Ancestry trees. ↩

- Martindale, p. 194. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book P, p. 299. ↩

- Martindale. ↩

- Her maiden name may have been Hoagland. ↩

- Martindale. ↩

- Philadelphia County wills, Book N, p. 6. The website of Mark D. Webster, “WebsterGriggsFamilies”, accessed March 2019, has documentation on the Parry family. ↩

- Montgomery County wills, Book 1, p. 435. ↩

- Website of Mark D. Webster. ↩