In September 1682 Edward Byllynge, one of the proprietors of West Jersey, sold 50 acres to James Cooper of Stratford upon Avon, Warwick, shoemaker, to be surveyed later.1 There are no records of when Cooper arrived, but he probably came in 1683, when many ships sailed from England full of Quakers bound for Pennsylvania and New Jersey.2 Cooper probably did not live on his West Jersey land, since by October 1683 he was in Philadelphia, getting a warrant from William Penn for a city lot to be laid out.

James married a woman named Hester; her last name is unknown. They were married either in England or Pennsylvania, but there is no record of the marriage.3 Since the records of Philadelphia Meeting are intact since its establishment, it is more likely that they married in England and immigrated together. James and Hester were both active as Quakers, but only after leaving and returning. Around 1692, James and Hester broke with the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting and followed George Keith, the charismatic founder of a separatist movement.4 Keith taught that reliance on the Inner Light as a source of truth was insufficient and urged Quakers to conform more closely to Scripture. The resulting schism led many to follow him out of their meetings, although some, like the Coopers, later rejoined.5 In 1695 James and Hester wrote a letter of acknowledgment to Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, where they had already returned.

“9th day 11th month 1695. Dear and faithful friends, brethren and sisters with whom formerly we have had dear fellowship in the spirit of Jesus (as also of late)… we are made sencible of that Spirit of Iniquity that doth Labour against the Operating Power of the Spirit of Truth and which hath captivated the soules of many and led in the way of untruth to witt prejudice enmity and seperation by George Keiths division and strive about things to no profit. Wherein as farr as we have bin concerned we do condemn disown and judge… we do desire we may be for the future kept in unity with you. Your poor afflicted Brother and Sister, James and Hester Cooper.”6

The experience of the separation seemed to deepen Hester’s religious feelings. She became a minister, one of a select group of men and women who were accepted speakers in the meetings. In 7th month 1701 Hester was one of three women who joined with fifteen men to form a group of approved ministers, in response to concerns from the Yearly Meeting about people who spoke inappropriately in meetings for worship. “Inasmuch as some painful instances had appeared both amongst Men and Women, in their using unseemly noises, tones and gestures, drawing their words out to a great length, and drowning the matter, also in the use of many needless repetitions in Doctrine, prayer, etc. For prevention thereof, and that the respective Meetings may be supplied with able Ministers, especially Philadelphia, it was agreed that there be a Meeting of Ministring Friends…”7 This group was supposed to serve the meeting in Philadelphia and others within a “moderate distance from the City, as to be conveniently visited from thence in a morning.”8 They were asked to correspond to “know each others minds as to avoid too many being at some Meetings while others are left without any.” The men who signed included such eminent ministers as William Penn, Thomas Story and Griffith Owen. Hester was in elite Quaker company.9

The Ministers met weekly, kept their own minutes, and signed up to attend the nearby meetings for worship.10 At the following meeting they would often report back how they found the meeting they had attended, “well”, “easy”, “not very open”, “a good meeting”. When Griffith Owen reported in 2nd month 1702 that the meeting at Frankford had a “dark drowsie earthly spirrit”, the others presumably knew exactly what he meant. There was noticeably less travel in the winter months. Hester was not active in 1702, but from 1703 into 1706 she travelled to nine different meetings, usually with a companion. For example, in 9th month 1704 she went to Radnor by herself, in 12th month 1704 with Martha Chalkley to Abington, in 2nd month 1705 with Anthony Morris to Bank Street meeting, the week after with Morris to Frankford, and in 4th month 1705 with Henry Willis to the Phila High Street meetings, one in the forenoon and one in the afternoon.11 Besides Martha Chalkley she went to meetings with Mary Lawson and Elizabeth Durborrow. The women ministers did not go as frequently as the men, but they appeared in a variety of meetings.12 In 5th month 1706 Hester went to Byberry with Hugh Durborrow and the Bank Street meeting with Ralph Jackson. This is her last appearance in the quarterly meetings of ministers.13

In 1701, the Philadelphia Meeting approved Hester’s request to attend the Yearly Meeting in Maryland, along with Elizabeth Key.14 Hester was included in John Smith’s 1785 list of “Persons eminent for piety and virtue among the people called Quakers”. As Smith put it, “Elizabeth Morris informs me that she was reputed an innocent and acceptable minister and died at Philadelphia.”15 From 1702 into early 1706 she was active in the Women’s Meeting of Philadelphia, presenting young couples to the Men’s Meeting after they had been approved for marriage and inquiring about the clearness of young women who wished to marry (freedom from marital promises to others).16

In 3rd month 1707, after she died, James Cooper came to the Women’s Meeting and presented a gift from Hester, “£2.10 as a legacy from his dear wife, which Friends accepts of as the last Token of her love.“17 Hester died in 10th month (December) 1706. Her death was noted in the minutes of the Yearly Meeting, where she was “raised in testimony”, an exceptional tribute from her fellow Friends.18

James was not a minister like Hester but he was active in the usual Quaker committees. In 6th month 1701 he was one of four Friends appointed to “look after the children that are disorderly or kept out of the meetings on First Days”.19 In 3rd month 1703 he was appointed to attend the Quarterly Meeting, and in 7th month to make inquiry about James Streator’s fitness for marriage.20 He was again asked to “take care that boys and young people be not disorderly about the meeting house on first days”, and was to discuss with workmen a new fence for the burying ground.21 In 1706 he and Hugh Durborough were appointed to take care of a matter about the widow Russell, reportedly in want because David Powell was detaining money from her.22

Some of James’ Quaker activities were not with his home meeting in Philadelphia but were instead with Byberry Meeting. Byberry was seventeen miles northeast of Philadelphia and would have been a long ride, although it was considered at a “moderate” distance for travel (as per the agreement of the Ministers in 1701). James’ first connection with Byberry Friends was in 6th month 1694, when he witnessed Henry English’s donation of land for a burying place for Quakers. Previously Byberry Friends had been buried on land of John Hart, but after Hart left to follow George Keith, the Friends remaining in unity needed their own land.23 Why was James active in a meeting so far from his home in Philadelphia? Had he already repented of his Keithian affiliation, but still felt estranged from the meeting in Philadelphia?24

James and Hester bought the rights to 50 acres in West Jersey in 1682, and sold the rights three years later to William Dillwyn, a saddler of Philadelphia.25 In October 1683 James Cooper went to Penn’s land office in Philadelphia to get a warrant for a lot in the city. Originally these lots were given by Penn as a bonus for people who bought land in the countryside, but by 1683 Penn saw the profit to be made in selling city lots. His warrant directed Thomas Holme to survey a lot, “thirty foot in breadth and in length as the rest of the lotts there.”26 The lot was surveyed, a return was filed with the land office, and Cooper got a patent for the lot in December 1684. This lot was on Chestnut Street, between fourth and fifth streets. It was soon rented to Robert Row and finally sold to him in 1695.27

In 1686 Cooper bought a part of a lot from Joseph Phipps where he and Hester would live for the rest of their lives and raise their family, and which served as the basis for the family’s solid economic status. This lot, with the addition of the other half from Phipps a year later, was divided into lots and rented out, providing the family with a yearly income of over £20 from the ground rents. The first piece was along Mulberry Street (present-day Arch Street), extending westward from the corner of 2nd Street. After buying the second lot from Phipps, Cooper owned most of the block of Mulberry between 2nd and 3rd Streets, extending over 300 feet along Mulberry. Starting in 1719, he rented out portions of the Mulberry Street land to others, including John Head, Grace Parsons, James Estaugh, and Henry Jones.28 After James’ death this land was partitioned out to the heirs.

James was a cordwainer, a shoemaker. Later he called himself a merchant. It is commonly said that he had a store on the corner of Mulberry and 2nd Street.29 He would certainly have sold shoes, and possibly other merchandise that people could not make themselves. Merchants of the time sold goods like paper, ink, nails, and cotton cloth.30 In 1693, Cooper just missed being in the top quartile of wealth in the city, with a valuation of £100 for his estate. (Samuel Carpenter led the list with £1300.)31 In 1710, with other merchants and tradesmen, James signed a petition to the General Assembly of Pennsylvania, asking for power for the Mayor and Aldermen to make ordinances, to build a watch house, erect a work house for the poor, and to repair wharves and bridges.32 In 1714 James Cooper requested a certificate from Philadelphia Meeting, since he “intends for New England upon his lawful occasions”.33 If this was James the merchant, he was probably going on a buying trip.

In 1706 Hester died, leaving James with eight children, most still living at home, and several still very young. As a well-off merchant he probably had a housekeeper to manage the household servants and supervise the children.34 He did not remarry for fourteen years, so the younger children were effectively raised without a mother. Perhaps that helps to explain why only two of the eight married in a Quaker meeting.

By 1711 the sons were growing close to maturity, and James bought his first land outside of the city, perhaps for his sons to settle on. He bought a 300-acre tract in the Manor of Moreland, in Philadelphia County from the heirs of Nicholas More. His sons James and Benjamin later lived on this tract.35 In 1714 Cooper bought 100 acres from John Brock of Byberry but sold it back to Brock a year later.36 In 1716 Cooper bought a larger tract, of 260 acres in Moreland, from Thomas and Elizabeth Groom. Nine years later James and Mary sold most of this to his son Samuel.37 Two other transactions were probably meant as investments, at a time when there were few options for getting a return on excess capital. In 1723 James bought 150 acres in Great Swamp in Bucks County, in the far northwest corner of the county, later called Richland Township.38 Originally too far from Philadelphia, land there became more settled about 1720. None of the family settled on the tract, and it was sold at a loss by the heirs after James died. Another transaction, for 200 acres on Neshaminy Creek in Northampton, Bucks County, was never completed.39

In 1722 James applied for a certificate of clearness in order to marry Mary Borrows of Falls Meeting. They were married the following month but had no children together.40 In 10th month 1732, James and Mary were buried on the same day.41 James died before he could sign his will, and although it was admitted for probate there were blanks for the date and name of his executors. According to testimony of the witnesses, he intended to appoint his son Samuel to be executor, along with John Cadwallader. But Samuel lived out of the city, in Moreland township, and James wanted him to be there for the signing of the will. Sarah Elfreth said that when Cooper was at her house about ten days before he died, he told her that he wanted to settle his affairs and wished that his son Samuel was in town.42 The will was admitted to probate and letters of administration were granted to Samuel and to John Cadwalader.

The provisions of the will were typical of the time. Mary was to have one third of the rent from the real estate and one third of the personal estate. Esther received £10 per year from the rents. Isaac also got £10 per year, and “if he be restored to his former capacity” and marry, then his heirs were to have the annuity. Rebecca and the only named grandson, James son of James deceased, were to have an annuity, but only after the death of Mary and Isaac. The remainder of the estate was to be divided among Samuel, William, Benjamin, Isaac, Esther, Rebecca and the grandson James. The son Joseph had died before his father, leaving no heirs. There was no legacy to Philadelphia Friends, although some well-off Quakers did this.

The inventory shows that James was wealthy but does not suggest that he kept a normal dry-goods shop. There was a bountiful list of his household goods, plus the land in the Great Swamp and a 40-acre tract in the Manor of Moreland. The business is reflected in the bonds from 56 different people, from Philadelphia and Bucks County. Cooper probably kept an account book for his business, to manage these debts owed to him.43 The inventory did not include shoemaker’s tools or dry goods such as quantities of cloth or nails. It did include 2 ½ dozen knives, 1750 feet of boards,1200 feet of scantling (small lumber), and 3000 bricks. Was he in the process of building a house or did he sell building supplies? The total value of the estate was over £855, wealthy for the time.44

Two years after James and Mary died, the heirs faced the challenge of dividing the main asset, the land on Mulberry Street. James had not specified that in the will, leaving it for them to do. They solved the problem in an unusual way. There were seven of them, the six surviving children and the grandson James who was entitled to a double share, as his deceased father James was the oldest son. The grandson James and his wife Susannah sold their two shares to Samuel Cooper, leaving six people to divide the property into eight shares. They met together in the Manor of Moreland, and divided it up, numbered each share, put each number on a piece of paper, put them into a hat, shuffled them together, and took turns drawing out the numbers. Samuel went first and drew his three shares, and the others followed, each drawing one share. They wrote out the results in a complex partition deed and proclaimed themselves “fully satisfied contented and agreed”.45 Some of the lots were less valuable than the others, probably because some were vacant and others were rented out, but they balanced the values with a system of payments between themselves. For example, whoever drew lot eight would get yearly payments from the holders of three other lots, and the holder of lot six paid yearly to that of lot one. This appears to have been an amiable process, since it bound the siblings together in a web of yearly payments for as long as they owned the land.

It is noteworthy that only the two daughters married in Philadelphia Meeting. The sons either did not marry (Joseph, probably Isaac, possibly Samuel) or married outside of meeting (James, William, and Benjamin). All apparently stayed in or near Philadelphia.

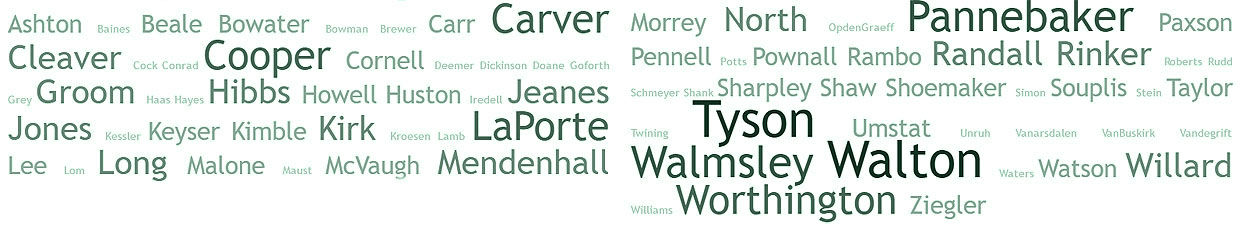

Children of James and Hester:46

Esther, b. about 1683, m. in 1705 Jedediah Hussey of New Castle, Delaware. James and Hester went to the Philadelphia MM to give their consent to the marriage. Jedidiah, born in 1678, was from a large Quaker family that moved from Massachusetts to New Castle County.47 Esther and Jedidiah lived there and had four children: Rebecca, Jedidiah, Sylvanus and Esther.48 Jedediah died in 1734. In his will he left one third of his estate to Esther, £50 to his daughter Rebecca, the plantation and two mulatto girls to his son Sylvanus, a young colt to Susanna his former servant, a house and lot to his daughter Esther, a portion to his “poor afflicted son Jedediah”, which was to belong to Sylvanus for the care of Jedediah. It is not known when Esther died.

James, b. ab. 1684, married but his wife’s name is unknown, died before 1732, lived in Moreland, Philadelphia County.49 James was a member of Byberry Meeting for a few years around 1714 to 1717. He lent the meeting £50 to build a meeting house, repaid by subscription in 1723.50 In 1717 he was one of 19 signers of the certificate of Giles Knight who was returning to England.51 In 1718 James Cooper, of the Manor of Moreland yeoman, lent money to both Oddy Brock and John Brock; they each gave him a mortgage and both repaid the money.52 James’ only heir in 1732 was a son James, a shoemaker, who married Susannah Chaffin in 1733 at Christ Church.53

Joseph, b. ab. 1686, d. 1720. His death was noted in the records of Philadelphia Meeting: Joseph, son of James and Hester, died 7th month 4th day 1720.54 He left no heirs.

Samuel, b. ab. 1697, d. 1750, possibly unmarried.55 He lived in the city around 1734 and 1735 and called himself a cordwainer. By 1739 he was a yeoman of Moreland. He acquired valuable land in the city in the partition deed after his father died. In 1735 Samuel arranged with William Britton of Bristol Township, Philadelphia County. Samuel sold Britton the 210 acres in Moreland that his father had sold him in 1724, and left part of the purchase price (£200) in Britton’s hands in return for Britton “to provide the said Samuel Cooper in meat drink washing loading and mending of apparel during all the days of his natural life”.56 Samuel died in 1750. He left a will, leaving land to his sister-in-law Mary Cooper (widow of William) and her sons, to his sister Rebecca Kelly, and a residual legacy to his niece Esther Hussey, to Rebecca Kelly’s children, and to his cousin James (son of James). He also left £30 to Rachel Britton, wife of William Britton, perhaps in gratitude for her services in caring for him.57 The inventory of his estate showed comfortable furnishings for one room and a few luxuries like an ivory cane.

William, b. about 1699, d. 1736, married before 1726 Mary Groom, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth of Byberry. They lived in Byberry, where he was taxed in 1734. William and Mary had six known children: Rebecca, Thomas, James, Joseph, Samuel, Letitia.58 William died in 1736; he did not leave a will. Mary outlived him by many years, dying in 1772. William and Mary were the great-grandparents of James Fenimore Cooper, through their son James.59

Benjamin, b. about 1700, m. 1720 Elizabeth Kelly at Christ Church, Philadelphia, lived in Moreland. Taxed in 1734 for 100 acres there.60 It is not known when Benjamin or Elizabeth died. Since they do not appear in Samuel’s will, they probably died before 1750 and left no children.

Isaac, b. ab. 1701, in 1734 he was named in the partition deed as a tailor of Philadelphia. Since he does not appear in Samuel’s will, he probably died before 1750 without heirs.

Rebecca, b. ab. 1703, d. after 1735, married first 1726 Ralph Hoy at Philadelphia Meeting, married second in 1735 Daniel Kelly at Christ Church. Rebecca’s first husband, Ralph Hoy, was a weaver from Yorkshire, who arrived in 1725 at Middletown, Bucks County, but soon moved to Philadelphia, where he married Rebecca in 6th month 1726. They had a daughter Elizabeth (who married Francis Kelly in 1747 at Christ Church). Ralph died by February 1734, when Rebecca signed a deed as his widow.61 In September 1735 she married Daniel Kelly. They had at least one child, mentioned but not named in Samuel’s will of 1750.62

- The family of James Cooper has been well documented because he and his wife Hester were the great-great grandparents of the novelist James Fenimore Cooper. The website of the James Fenimore Cooper Society includes two genealogies of the Cooper family, one by William W. Cooper in 1879 and one by Wayne Wright in 1983. Both have been used throughout this account. The one by William Cooper has extensive documentation for the first generation, while Wright added more recent evidence. James Fenimore Cooper believed that James Cooper the immigrant was the son of a William Cooper; others have repeated this as well, without providing a plausible candidate. The Cooper Society website is now at: https://jfcoopersociety.org/. William Cooper of Pyne Point, West Jersey, is sometimes named as a possible brother or even father of James Cooper. William Cooper was born in Coleshill, Hertfordshire, and immigrated to West Jersey where he bought land on Pyne Point and prospered. He named only two sons in his will of 1709/10, Joseph and Daniel, so he could not have been James’ father. (NJ Archive, volume 23, p. 108) There was a connection between William and James Cooper, but it is not conclusive; in 1688 James Cooper rented a lot in Philadelphia to William Cooper of New Jersey yeoman. (Philadelphia County deeds, Book E2, vol. 5, p. 89). This is interesting, but not unusual for the time, when there many transactions between Pennsylvania and Jersey people. It certainly does not prove that William and James were brothers. They were from different places, but Coleshill is only twenty-five miles from Stratford. The parish records of Warwickshire have been checked for a James Cooper, born about 1660 to 1661, with no results. (Ancestry.co.uk, Warwickshire, Church of England baptisms, marriages and births 1535-1812). William Davis in his History of Bucks County suggested, without evidence, that “the ancestor of the novelist was probably born in 1645, at Bolton, in Lancashire.” The problem is that Cooper was a very common name. In 1699 Middletown Monthly Meeting reported the arrival of William Cooper, his wife Thomasina and their children from Low Ellinton, Yorkshire. They remained in Bucks County and are confusable with the later family of James Cooper in records there. There was also a William Cooper of Philadelphia, who died in 1767, leaving five children, including, coincidentally, a Jacob who owned property on Mulberry Street. Jacob Cooper married Elizabeth Corker in 1742 at Philadelphia Meeting. Another James Cooper was a cloth worker of Darby (see below for more about him). These are probably five unrelated families, all sharing a common name. ↩

- Walter Sheppard, Passengers and ships, 1970. Byllynge apparently never came to West Jersey, but stayed in England, so the sale to Cooper must have been arranged there. ↩

- The records on Ancestry, All England & Wales, Quaker Birth, Marriage, and Death Registers, 1578-1837, were checked for any marriage of a woman named Esther or Hester to a James Cooper between 1674 and 1684. The English parish records on FamilySearch do not provide any results. The US Quaker records similarly come up without a match. (The marriage of Hester Gardiner to James Wills Cooper in Burlington in 1680 is not a match; James Wills was a cooper, not a Cooper.) Some web trees give Hester’s last name as Burrows; this is probably a confusion with Mary Borrows, James’ second wife. ↩

- Horle and Wokeck, in their magisterial work on Lawmaking and Legislators in Pennsylvania, volume 1, 1991, listed the signers of the various manifestos issued in 1691 and 1692 by the two sides: the conventional Quakers and the followers of Keith. Horle and Wokeck list James Cooper Junior and James Cooper Senior as signing Paper E, the June 1692 paper from 28 eminent Quakers disowning Keith. This is an error. Both men named James Cooper were followers of Keith, and neither signed the letters. The various letters, with their signees, are given in Keith’s The Judgement Given Forth by Twenty Eight Quakers Against G. K. and His Friends, 1693-94. Both men named James Cooper did sign the letter written in July 1692 at the house of Philip James by supporters of Keith. Neither one signed the letter from the Keithian group on 7th month 1692 at Burlington. ↩

- Horle and Wokeck cite a contemporary estate of 143 Quakers who left the traditional meetings. (p. 44). This estimate seems low. ↩

- Their letter was copied into Quaker records, Phila Monthly Meeting, Removals 1681-1758, 11th month 1695 (on Ancestry, US Quaker meeting records, image 296). Others rejoining about the same time included William and Sarah Dillwyn, William Preston, John Jones, and Robert Ewer. This letter of acknowledgment, along with the signatures on the letter of July 1692, poses a problem, because James Cooper Jr also wrote a letter of acknowledgment to Philadelphia Meeting in 1695, expressing his remorse for having followed Keith. (on Ancestry, US Quaker Meeting Records, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, minutes for 7th month 1695; text in Minutes 1695-1708, image 21). Who is this James Cooper Jr? He could not be the son of James and Hester, who would not have been old enough in 1695. He was not necessarily related to them. At the time it was customary to use Sr and Jr to differentiate two men of the same name, even if they were unrelated. The most likely candidate is James Cooper of Darby. He married first in 1698, so he was certainly younger than James Cooper of Philadelphia. Darby was ten miles from Philadelphia, so he could easily have shown up in meeting records there. If he was the follower of Keith, there is a good story about his involvement. In 1692 in Burlington, when the Yearly Meeting was in session, Keith issued a challenge to the Quaker establishment and sent a messenger to deliver it. Finding the door of the meeting house blocked, the messenger climbed up into an open window and read the challenge, continuing even though Thomas Janney was praying inside. The name of the messenger is not shown in the accounts of this confrontation, but in his letter of acknowledgment James Cooper Jr said, “That very day I read that paper so irreverently before a great congregation there met and gather to worship the Lord. To the grief of my heart I remember with what rigour I introduced it in the window where I stood.” After reading the paper he found George Keith, who said, “I have done with them, and I hope, when we die, they and I shall not both go to the same place.” This struck James Cooper with amazement and he thought to himself, “Surely this man wants charity.” (The Friend, vol. 28, 1855, p. 51, where the letter of acknowledgment is quoted in full but wrongly attributed to the husband of Hester Cooper.) Five years later James Cooper of Darby found himself in another controversy. Margaret Jenner, an elderly Swedish widow, left her property to her three children and made James Cooper and Paul Saunders, non-relatives, her executors. A month later, on the reverse side of the will, she added a legacy to “my executor James Cooper one half of my meadow lying and being upon the other side of Peter Yokum’s island … to defend my meadows against all that shall lay claim or endeavor to wrong my children when I am dead.” Her siblings filed a caveat and petitioned the Council, claiming undue influence on an old woman not in her right mind. After much eye-witness testimony, William Penn himself declared the will valid, and Cooper and Saunders were left to execute it. (Philadelphia County Will 1701, #51, Book B, p. 129) ↩

- Letter from 18 Friends, Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Minutes 1762-1806, on Ancestry, US Quaker Mtg Records, image 301. ↩

- The meetings were Germantown, Frankford, Merion, Radnor, Haverford, Abington, Byberry, Newtown, and Northwales. ↩

- The profile of Hester in The Friend, volume 28, 1855, p. 51. ↩

- Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting, minutes 1701-1727, on Ancestry, US Quaker Mtg Records. The Griffith Owen quote is on image 25. ↩

- Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting, minutes 1701-1727, image 93 through 100. ↩

- Hester went with Mary Lawson to Plymouth, Byberry, and Abington, with Elizabeth Durborrow to Byberry, and with Martha Chalkley to Gwynedd, Philadelphia, and Abington. ↩

- Image 114. Hester’s name does not appear in the early minutes of the Quarterly Women’s Meetings at Phila. (Ancestry, Phila Q Meeting, Minutes 1692-1792). Perhaps because she was active in the minister’s group, she was not also called upon to attend quarterly meetings as a delegate from Philadelphia. ↩

- Philadelphia Monthly Meeting minutes, 7th month 1701, in Ancestry, US Quaker Mtg Records, Phila MM, Minutes 1682-1705, image 105. Note that Watring, Early Quaker Records of Philadelphia, volume 1, has “Hess” for “Key”. There are several copies of this minute online; some are clearer than others. ↩

- John Smith, “Memoirs concerning many persons Eminent for Piety and Virtue among the people called Quakers”, three notebooks, written about 1785-1787, on Ancestry, US Quaker Mtg Records 1681-1935, Phila Monthly Meeting. The three parts are named as : Minutes 1646-1757, Minutes 1666-1789, Minutes 1667-1761. Esther’s memoir is in part 1, image 45. ↩

- Philadelphia Men’s minutes for 4th month 1702, 3rd month 1704, 6th month 1704 and Women’s minutes for 4th month 1702, 8th month 1703, 6th month 1704, 7th month 1704, 3rd month 1705, 1st month 1706. ↩

- Philadelphia Monthly Meeting Arch Street, Women’s Minutes 1686-1728, p. 57, image 48. ↩

- Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Minutes, online at Ancestry, Minutes 1682-1713, image 81. Since Hester was still having children as of about 1703, it is possible that she died as a result of complications of childbirth. ↩

- Phila MM, Minutes 1682-1714, 6th month 1701, image 159. ↩

- Phila MM, Minutes 1682-1714, 3rd month 1703 (image 184), 7th month 1703 (image 188). ↩

- Phila MM, Minutes 1682-1714, 5th month 1703 (image 185), 7th month 1703 (image 187). ↩

- Philadelphia Men’s Minutes, 5th month 1706, in Minutes 1706-1709, image 7, 10, 11. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, E2, vol. 5, p. 279, online at Phila-records.com/historic-records/web, Roll 10, image 142. ↩

- His son James was not yet old enough to sign a document as a member. There is not enough material to postulate an entirely different James Cooper on the basis of this one record. All the other transactions of the Coopers in Byberry can be attributed either to James Cooper, the merchant of Philadelphia, or to his son James when he came of age. ↩

- Gloucester Deeds, originally in Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, now online at the West Jersey History Project. The land was apparently laid out on Cooper’s Creek, named for William Cooper of Pyne Point, but this coincidence does not show a relationship between James and William Cooper. ↩

- Copied Survey Books, D71-280, on the website of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ↩

- Warrant and Survey Books, entry #2670, at the Philadelphia Archive; Patent Index Book A, p. 81, on the PHMC website; Blackwell Rent Roll, in Hannah B. Roach, Colonial Philadelphians; Philadelphia County Deeds E2, v5, p. 295 (Deed to Robert Row for a lot 30 feet by 178 feet granted to Cooper by patent in 10th month 1684). ↩

- Rental to John Head, cabinetmaker, March 1719, Philadelphia County Deeds, book G1, p. 99; to Grace Parsons, widow, book F4, p. 229; to James Estaugh, boulter, book G4, p. 278; in 1728 to Henry Jones, tailor, book F10, p. 238. ↩

- Hannah Benner Roach, Colonial Philadelphians, 2007, and the William W. Cooper genealogy of the family. ↩

- Frederick Tolles, Meeting House and Counting House, 1948. ↩

- 1693 tax list of Philadelphia City and County, PA Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 8, 1897. ↩

- Samuel Hazard, Register of Pennsylvania, vol. 4, July 1829 to January 1830, p. 29. James Cooper was also supposed to have signed a petition to King William in 1694 with other Friends. (W. W. Cooper, 1879) This reference has not been traced. ↩

- Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Minutes 1705-1714, online on Ancestry, image 100. In 1705 James Cooper Jr requested a certificate to go to Barbadoes. (11th month 1705). Who was this? ↩

- For example, the family of Henry and Elizabeth Drinker was supported by Elizabeth’s sister Mary Sandwith, who never married and lived with them for fifty years. She managed the household, hired and supervised the servants, tended the children. She was so important to the family that Henry wrote to Elizabeth that he felt especially “clever… to have two wives”. (Karin A. Wulf, Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia, pp. 85-87.) In the family of Humphrey Morrey, wealthy merchant of Philadelphia, the housekeeper was Jane Laurence, remembered in Humphrey’s will in 1715 (Philadelphia County Wills, Book D, p. 49, proved in 1716). Jane in turn left money to Humphrey’s children in her own will in 1735 (Will Book E, p. 346). ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, Book E7, v. 8, p. 78, online by subscription at phila-records.com/historic-records/web, roll 11, images 338-341. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, Book E7, v.9, p. 350. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, Book H17, p. 154, on September 1, 1725. ↩

- W. H. Davis, History of Bucks County, chapter on Richland. ↩

- It was entered in the Bucks County Deed book by mistake, with a note that the clerk made an error. (Bucks County deed book 13, pp. 385-386.) ↩

- Minutes of Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, 6th month 1722, also the Women’s Minutes of 10th month, where the marriage was reported accomplished. There was a Borroughs family in Falls township, but Mary’s parentage has not been traced. ↩

- Anna M. Watring, Early Quaker Records of Philadelphia, vol. 1, 1997. They were buried on 6th day 10th month. ↩

- Philadelphia Wills, City Hall, Will Book e, p. 219, 1732. Sarah Elfreth was probably the wife of Henry Elfreth and a neighbor of the Coopers. Her father John Gilbert owned a lot on the east side of 2nd Street, where the alley known as Gilbert’s Alley later became the well-known Elfreth’s Alley. (Elfreth Necrology, Publications of the PA Genealogical Society, vol. 2, pp. 172-174). ↩

- His tenant John Head, a cabinetmaker, kept such a book, which was preserved and recently published by the American Philosophical Society. ↩

- Philadelphia County will packets, City Hall. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, G6, p. 419, August 2, 1734. It is a complex document. The shares were not completely equivalent in value, so to make a fair division the owners of some properties had to make yearly payments to the holders of other properties. For example, Rebecca Hoy drew paper number seven and had to make payments of £0.15.3 per year to the holder of paper number eight, her brother William. The partition deed omitted the month and day and was dated only as 1734. In the acknowledgment before the justice on July 4, 1735, John Campbell swore that he had witnessed the signing on “the second day of August last past”, which is to say August 1734. ↩

- There is no record of their births in the records of Philadelphia Meeting. The dates here are estimates based on the dates of their marriages, and on the order named in James’ will. ↩

- Horle and Wokeck, vol. 1; Herbert Standing, “Quakers in Delaware in the time of William Penn”, 1982, pp. 137-39 (available online at nc-chap.org/church/quaker/standingDH3crop.pdf, accessed 2/2019). ↩

- The children are named in his 1734 will. (New Castle County wills, Misc vol. 1, p. 193, online on FamilySearch, Misc Will records v. 1-2, 1727-1788, p. 193) Interesting names run in the Hussey family: Sylvanus, Batchelor, Theodate, Puella, etc. Sylvanus later sold his share of the estate, and the responsibility for caring for Jedidiah, to Stephen Lewis, his brother-in-law (husband of Rebecca). ↩

- There is no record of the marriage in Philadelphia Meeting records. Did the sons fall away from the Quakers? ↩

- Joseph Martindale, History of Byberry and Moreland, 1867, p. 45. Record of this loan has not been found in records of Abington Meeting (the parent monthly meeting for Byberry). ↩

- Martindale, p. 301. ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, book F1, p. 190, 198 (online roll 12, repaginated, image 507 and image 511). ↩

- In February 1733/34, William and Mary Cooper were the administrators for Samuel Cooper, late of Philadelphia, as the next of kin. (Administration Book C, in PA Genealogical Magazine, vol. 22) This could not be William’s brother Samuel, who died in 1750. The only brother who could have married soon enough to have a son of age in 1734 is probably James. But this Samuel is not mentioned in the will of James Cooper, written before March 1732. In spite of the coincidence of names, Samuel probably belongs to another family. ↩

- Watring, Early Quaker Records of Philadelphia, vol. 1. ↩

- The Cooper Genealogy (W. W. Cooper, 1879) claimed that he married Sarah (?Dunning) and had children Jacob and Rebecca. Considering the other Cooper families around, this cannot be accepted without evidence. Samuel named no wife or children in his will. There was a Mary Cooper who died in 1732, according to records of Philadelphia Meeting. Was this a wife of his? ↩

- Philadelphia County Deeds, Book H17, p. 149 (online roll 28, image 202). This was a fairly standard arrangement for someone like Samuel with no heirs. ↩

- Philadelphia County Wills, Book J, p. 322, File #207, 1750. ↩

- The Cooper Genealogy. The son James married Hannah Hibbs. William, son of James and Hannah, was the father of James Fenimore Cooper. Rebecca and Thomas also married into the Hibbs family. ↩

- The Cooper Genealogy, 1879 and 1983. ↩

- It is sometimes claimed that he moved to Virginia in 1725 and had sons Fleet and Thomas. This claim started with Murphy R. Cooper, author of the Cooper Family, but has been debunked by John H. Croom, with an exhaustive review of the evidence on his website. ↩

- Bucks County Church Records, vol. 2, p. 259; Philadelphia MM Certificates of Removal 1686-1772; Philadelphia MM minutes 1696-1750; Philadelphia County deeds H1, p. 47, a release by heirs to John Parratt. Note that there is no mention of Ralph as Irish in the certificates of arrival (in spite of the record in Albert Cook Myers, Quaker Arrivals to Philadelphia). Also note that there is no known relation between Francis Kelly and Rebecca’s second husband Daniel Kelly. In 1750 Daniel Kelly was a witness for the will of Thomas Foster of Lower Dublin, Philadelphia County. Other witnesses were Joseph Kelly (a brother?) and William Brittin, who cared for Samuel Cooper for years (Philadelphia County will book J, p. 365). ↩

- William W. Cooper gave her date of death as 1755 (Cooper, 1879), with no evidence. ↩