It was a moonlit night, a Thursday in May in Huntingdon County. John Burket was a music teacher. He had been teaching the band at the Cross Roads near Warrior’s Mark.1 He was walking home when he saw a dead man lying by the road near Thompson’s Lane. He called to a few men who were sitting on a fence nearby, “Boys, come here. There’s a man with his throat cut.” The man’s throat was cut from ear to ear and his head was bruised and cut. A bloody stone was found nearby. It was May 28, 1885.2

When the body was identified as that of John Irvin, suspicion immediately fell on Jack LaPorte and Jacob Harpster, who had been seen in Irvin’s company that night. Irvin and LaPorte worked together at Shoenberger’s mines near Warriors Mark. Irwin was a fireman on a boiler and LaPorte fired an engine. On Thursday they spent the day drinking at Chamberlain’s hotel with a few friends. By evening the proprietor noticed they were drunk, refused to sell them any more liquor, and tried to send them home. Three of them left, leaving Irvin and LaPorte together. They stood outside the hotel for a while and threw stones at it, without doing any damage, then started down the road where they encountered Harpster. They stopped by a tinner’s shop, where the tinner accused Harpster of stealing some rivets and threatened to call an officer. They ran away, but Irvin and LaPorte insisted on going back to finish the business with the tinner. Harpster left them and that was the last he saw of Irwin.

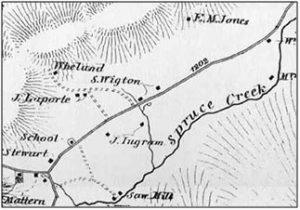

The next morning a warrant was issued for LaPorte’s arrest. The officers could not find him in Warriors Mark or at his father’s house in Franklinville. After dinner he turned up at the house of his brother Hunter, who was living on the family homestead near Franklinville. His father met him there and told his son that as an officer of the law he was duty-bound to deliver him to the Sheriff. So he harnessed the horse and drove to Spruce Creek to take the first train to Huntingdon, then to the jail. (The New York Times was impressed with this and called it a “heroic action” by a judge who put his duty above his loyalty to his son.)

The local paper reported that Jack was born in Spruce Creek Valley, about two miles from Warrior’s Mark. He had been employed as a clerk in Tyrone for several years, but was discharged due to his intemperate habits and for showing “traits of insanity”. It was said that his mind would wander and that he was a queer character. In his cell he passed the time reading and thinking, sleeping with a light on, and refused to be interviewed. Irvin was a sturdy, strongly-built man, known as a drinking man and quarrelsome. He was the sole support of his widowed mother, which generated some sympathy with the local people.

The trial started in mid-September and was reported as far away as New York, where the Times covered it as a sensation. More detailed reports came from the Huntingdon Globe, the local paper.

Wednesday, September 16, 1885: The trial was set to begin. Judge John LaPorte sat with his fellow judges for the preliminaries of bringing in the grand jury indictment, but he left the bench before his son was brought in by George Garrettson, Deputy High Sheriff of Huntingdon County.3

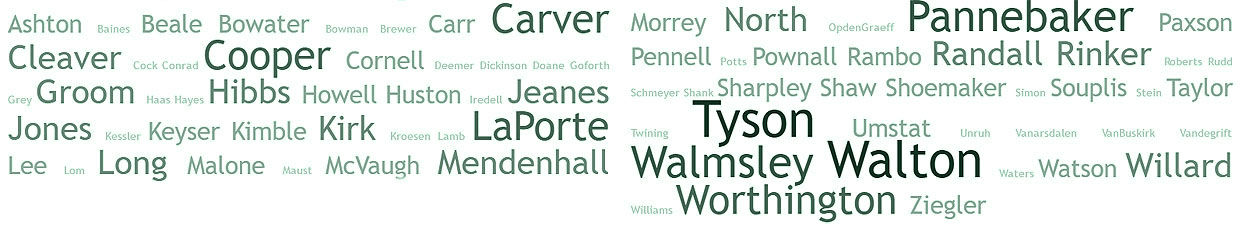

Thursday, September 17: The trial began by choosing a jury of twelve men, from all around the county. The defendant, Jack, was described as handsome, about 5 feet 10 inches, with jet black hair and moustache and a full face. The prosecutor was Mr. Orlady; there was a team of three defense attorneys. (The family spared no expense for the defense, both for the lawyers and for the expert witnesses.)

John Burket described finding the body. A barlow knife was later found about 100 feet away in a meadow. Upon analysis by a professor of chemistry at State College, traces of blood were found on the knife.

Thursday, September 24: William Weaver was called to testify, and his testimony seemed quite damaging to the defendant. Weaver had been working on the road on the evening of the murder. He saw LaPorte, Irvin and Harpster about 6:00. LaPorte said to Irvin, “Let’s have a drink.” Irvin pulled out a bottle and Weaver and Harpster each had a swig of whiskey. LaPorte vomited. They all sang “We’ll go and see Dolly tonight.” They walked off down the road together till they reached the lane where Weaver turned off. Harpster headed home. Weaver looked back and saw LaPorte going toward Warriors Mark and Irvin getting a ride on a wagon toward Huntingdon Forge. Around 9:00 Weaver heard voices out on the road. One said, “By —- I’ll brain you.” Then, “Oh! no Jack, you won’t do that,” followed by “Yes, by God.” It was not long after that when another man came by in a buggy and cried, “Come down, come down; come for Jesus sake!” It was Robert Henderson who was calling Weaver to come and see the body.

Harpster testified to the same story. He and Irvin and LaPorte left Warriors Mark and headed toward Thompson’s Lane, where they met Weaver and another. They drank a little whiskey together, then Harpster headed toward the toll gate. Irvin passed him riding on a wagon, which Harpster tried to climb onto as well. When he got to the gate house, Jim Irvin was there sitting on a stone. They walked together for a bit but then LaPorte caught up to them and he and Irvin went off together in the other direction toward Warriors Mark, while he himself went to Richardson’s shanty to spend the night.

James Gillam saw LaPorte three or four times that evening. He bought a few cigars, asked to borrow a dollar, and got fifty cents from Gillam. The last time he came in was about 8:45, and he was looking for Irvin.

Antis Ellis saw Irvin and LaPorte leaving the hotel around 9:00, angry because Chamberlain wouldn’t give them any more liquor. LaPorte said “I will stone Spangler or kill some other fellow tonight.” When Irvin went up to John Lower and tried to start a fight, LaPorte separated them and said “I’m your superior, sit down.”

Squire John Kinch, the justice of the peace, testified that Judge John brought Jack to him at 4:00 in the afternoon on the 29th. He asked Jack why he killed Irvin, and Jack replied that he didn’t kill him. When Kinch asked Jack whether he had scuffled with Irvin, Jack admitted it. When asked why he didn’t come home that night, Jack claimed that he didn’t want his mother to see him because he had been drinking and was sick. There was testimony from several witnesses to the effect that the knife which was found in the field was not LaPorte’s knife.

Finally the defense opened its case. Mr. Speer outlined the case. First they would show that the defendant was insane, with hereditary insanity running in both sides of his family. His mother’s mother, his father’s mother, his father’s sister, his brother, and Jack himself—all would be shown to suffer from various signs of insanity. Further the defense would show that when Jack was sober he was a model companion, but that excessive drink destroyed his moral and mental attributes.

Samuel Jones Esq. of Tyrone was the first witness called. As the brother of Jack’s mother, he testified that his mother had become deranged around 1813, according to family tradition, and that he remembered her periodic attacks of insanity from 1826 on, lasting a year or so, followed by periods of lucidity. From 1866 to 1872, when she died, she was “radically insane.” Samuel’s sister Nancy became insane at the age of 38, which lasted two years. She was afflicted at various times throughout her life and died in the asylum at Harrisburg in 1872.

Friday, September 25: Judge LaPorte was sworn. He stated that his son Lemuel had died in the insane asylum in 1875 at the age of 35. Lemuel strongly resembled Jack. The judge first noticed mental unsoundness in Jack two years before. He was taciturn and reserved, and “would often start in one direction and then retrace his steps as if undecided where he wished to go.” When he first saw Jack on the day after the murder, Jack seemed wild and frightened. His clothes were wet. After he changed out of the wet clothes, they walked to Squire Kinch’s house to whom he said, “I have brought this man to put him into your custody, and we waive a hearing.” The judge denied that Kinch asked Jack why he killed Irvin or that Jack had admitted to a scuffle.

At some point that afternoon Jack said to his father, “If I had six grains of arsenic, I would relieve you of this trouble.” It was the only time he had ever heard Jack talk of suicide.

Mary LaPorte, Jack’s mother, testified that she helped Jack change his clothes that morning and noticed a lump on his forehead and a cut on his lip. Jack’s sister, Mrs. C. B. McWilliams, testified that she and her husband heard of the murder on Friday and drove to the judge’s house that afternoon in time to see Jack go up and change his clothes. Her husband asked Jack, “What got over you last night?”, to which Jack replied, “I don’t know.”

Before he went home that afternoon, Jack stopped at Hunter and Elizabeth’s house about 2:00 and asked for something to eat. He apparently also took off a bloody shirt and left it there. She testified that she gave it to the authorities without cleaning it and that she knew nothing of any shirt being burned at her house that day. Hunter stated that Jack admitted to having a “drunk and racket” with Irvin the night before. Jack felt sick and lay down for a while in the hay outside. Then he came back inside and complained, “Hunt, this is a devil of an affair.” When they told him that the authorities were looking for him, he said he didn’t know anything about it. Mrs. Sarah Myers of Tyrone, sister of Mary Ann, corroborated the story of insanity in the Jones family. Mrs. John Ingram testified to the mental condition of the defendant’s grandmother and aunt.

A parade of witnesses tried to establish insanity in Jack’s behavior. C. J. Kegel of Tyrone, who had hired Jack as a clerk, had fired him because of mental instability. In particular he told a story that Jack had ran into the store and asked to be released because he had just agreed to leave at once for Australia with a man he had met. John Wigton of Franklinville reported that Jack liked to wear his working clothes on Sunday and his best suit on Monday, among other peculiarities. James Morrow of Tyrone reported that once he and Anson Laporte took Jack back to Anson’s room at the Eagle Hotel in Tyrone and that Jack, who was drunk, broke the lock on the door in trying to get out. But the next morning he didn’t remember anything about it. Minnie Waddle and Dr. Piper both testified about occasions when Jack seemed dazed and confused but not drunk. On one of these he said to Minnie, “What is the use in our living? We had both better be dead.”

At the same time the defense tried to show that Jack had a good reputation. W. Fisk Conrad Esq. of Tyrone testified that he had known Jack since he was ten years old and had always considered him a model citizen. James Shultz, manager of the Shoenberger mines, testified that LaPorte had an excellent reputation at the mines, while Irvin was quarrelsome and had been discharged three times for disobeying orders.

After ten hours of summation by the lawyers on both sides, the judge gave his charge to the jury, regarded on both sides as a fair charge. The jury retired, with an injunction from the judge not to leave their room until they had reached a verdict. Not surprisingly, the court house bell rang soon after to indicate that the verdict was reached. “Hundreds rushed pell-mell through the streets and filled the temple of justice. In seven minutes the large room was packed from pit to dome by old and young, and many were unable to gain admission.” The jury filed in and the foreman Mr. J. C. Dunkle returned the verdict of guilty of murder in the second degree, a verdict which was accepted as fair by the people.

October 22, 1885: The sentence. Judge Furst addressed Jack LaPorte before sentencing. He said that the defense was very competent and that everything possible had been done that could be. The jury had given careful attention to the case. He added that “We are well satisfied that you killed your friend and companion. We think we can trace the crime to your intemperate habit in the use of strong drink…..There was but one person save the eye of the Almighty who saw how this offense was committed; and whether there was any circumstance of provocation or of excuse you yourself know that fact—no other. We have taken into consideration, Mr. LaPorte, your youth and the hereditary taint of insanity that is in your family….There is one person living who will suffer as much—even more than yourself, and that is your aged mother…You are young in life and you should make your resolution here, if you have not already made it, that from this time until the day of your death you will never touch a drop of liquor; because with your habit and temperament the day may come when you will answer for murder in the first degree…The court after comparing differences of opinion, (and I will say here that I have held private consultation with your father and have differed with him), we have arrived at what we believe to be a proper measure of punishment in view of the circumstances of the case.”

Judge Furst then sentenced Jack to six years of “separate and solitary confinement” in the Western Penitentiary.

October 29, 1885: Sheriff McAlevy took Jack to the penitentiary. Jack was “docile”, “kind-hearted”, and did everything he was asked. They sat together in the smoking car of the Pacific Express. No handcuffs were used. “Jack seemed to enjoy the scenery very much.” (He had probably never been to Pittsburgh on the train before.) After arriving in Pittsburgh, the sheriff gave him a splendid dinner at the Seventh Avenue Hotel and then delivered him to the penitentiary where he put on his prison uniform. “The parting between the Sheriff and Jack was very affecting. As they were about to leave each other Jack warmly grasped the hand of the Sheriff and said: ‘Sheriff, good bye, I may never see you again in this world; you have been good and kind to me and I thank you for it. If we should never meet here again, I hope we will meet in that far off better land.’”

- There is still a road in Warrior’s Mark called Burket Road, just south of the crossroads. ↩

- Huntingdon Globe, microfilm at Juniata College Library, Huntingdon. ↩

- Court records, Huntingdon County Courthouse. These records contain only minimal description of each day’s events. They are not a transcript of the testimony. Fortunately the newspaper accounts were detailed. ↩