Gunnar Rambo was born on January 6, 1648/49.1 He was the oldest son of Peter Gunnarsson Rambo and Britta Mattsdotter, and grew up on his parents’ farm in Passyunk, on the Delaware River south of Philadelphia. In 1670 he married Anna Cock, daughter of Peter Cock and Margaret Lom. The Cock and Rambo families were two of the most prominent among the Swedes, linked by marriage and by the shared service of Peter Rambo and Peter Cock in the courts.

Gunnar and Anna moved to Shackamaxon, a few miles north of Philadelphia, along the Delaware River.2 The creek that empties into the Delaware around modern-day Kensington was named Gunnar’s Run, after Gunnar. They were living there when the Quakers arrived in large numbers, starting in summer of 1682. Tradition says that Penn met the Indians at Shackamaxon to sign a treaty of peace, commemorated in the famous painting by Benjamin West.3

In January 1683, Gunnar was naturalized, along with his father Peter and other Swedes.4 He became a citizen, able to serve on juries and in the Assembly. Gunnar would do both. In 12th month 1683, he was called to serve on the grand jury in Pennsylvania’s only witchcraft trial. He was the only Swede on the jury. Margaret Mattson was hauled before the Provincial Council, accused of being a witch.5 Penn presided over the case and a grand jury was called. They found enough evidence to bring her to trial and a parade of witnesses came forward. Margaret did not speak English and Lasse Cock, Anna’s brother, was called to interpret. Henry Drystreet testified that he was told 20 years before that she could bewitch cows. James Sanderland’s mother said that her cow was bewitched. Charles Ashcom testified that Mattson’s daughter sent for him one night because she saw an old woman with a knife in her hand standing at the foot of the bed. Annakey Vanculin and his husband John believed that their cattle were bewitched, and in order to prove it took a heart of a dead calf, and boiled it. (There was a superstition that this made the witch feel the burning pain, and that she would have to come to them to break the spell.) In fact, they claimed, Mattson did come in and asked them what they were doing. When they told her, she said “they had better they had boiled the bones”. Mattson in her defense denied going into their house, said she was never out of her canoe. She also pointed out that the other evidence against her was hearsay, saying, “Where is my daughter? Let her come and say so.” The jury brought in a verdict that she was guilty of having the fame of a witch but not of witchcraft, a judicious compromise. Her husband posted bond for her good behavior for six months, and that was the end of it.

In 1685 Gunnar was elected to the Assembly.6 (His brother Peter would also serve there.) The Swedes had maintained good relations with Penn in the earliest years, when he depended on them to act as translators and intermediaries to the Indians. But in the Assembly they generally sided with the country party, led by David Lloyd, which was often at odds with the proprietor and those who supported him. It is not known how Gunnar dealt with the politics of the Assembly.7

In November 1677, Gunnar had petitioned the Upland court along with his brother Peter and brother-in-law Lasse Cock; they wanted to settle in a town on the Delaware river near the falls, each with a hundred acres of land and a bit of marsh, somewhere around present-day Bensalem. The court rejected the petition, probably because the Indians still had title to the land.8 Instead he and Anna settled into farming at Shackamaxon. They duly paid the quitrents each year, and saved the receipts, which became important in 1691, when the Board of Property asked for proof of ownership. Gunnar went with his neighbor Michael Neelson before the Board and showed his receipts, and in return he was granted a patent for his lands.9 In the 1693 tax list of Philadelphia County, Gunnar was listed in the Northern Liberty, and taxed for property worth £100, somewhat in the middle range of property-owners.10

In 1696 Gunnar and his brother John bought land in Upper Merion. This was 20 miles up the Schuylkill River from Philadelphia, and considered very much up-country, with few roads and sparse settlement. A deed of 1699 refers to Gunnar as “now residing above the falls of the Schuylkill”, so he and Anna must have moved their family north between 1696 and 1699. In 1701 it was discovered that their land lay within the boundary of Penn’s Manor of Mount Joy, granted to his daughter Laetitia. To rectify the error, Penn ordered a survey for Gunnar, which was done and a patent granted to him. The story is that Penn was willing to sell land in his manor in order to make room for the English along the Delaware.11 Between 1712 and 1714, more of the Swedes settled around Upper Merion, including Gunnar’s son John, Peter Yocum, Matthias Holstein (married to Gunnar’s daughter Brigitta), and John Matson. They each took up tracts of several hundred acres, on the west side of the river, south of present-day Bridgeport. “On this tract the names of Swedes’ Ford, Swedes’ Church, Swedesburg, Swedeland and Matson’s Ford sufficiently indicate the presence of these settlers.”12

Their land was fertile and well-suited for farming.

“They choose excellent land. While southeastern Pennsylvania in general was very good for agriculture, the Swedes’ tract lay on probably the finest of the region. A rolling terrain, it had a deep, well-drained loamy soil, free of loose stones and enriched by limestone deposits. It lay athwart a limestone belt about a mile wide extending east to west until it widened into the soon-to-be fabulously productive Lancaster Plain. Several streams arose in or ran through the area, such as Matsunk Creek and Frog Run, although none of them was strong enough to propel a mill. Amply wooded, with oaks, hickories, and poplars predominating, by with open grasslands as well, the area abounded with wildlife – deer, turkeys, bears, wolves, foxes, squirrels, and an occasional panther. The woods supplied material for rafts and canoes and for log cabins. The limestone which ranged from hard marble to soft stone, not only fertilized the soil but also provided stone for chimneys and ovens and for building more substantial structures. The Schuylkill River, which enhanced the soil and supplied shad and catfish for the table, was not deep enough for large vessels except during the spring flooding, but rafts and canoes could be used for carrying the settlers and goods to and from the City. Because of Penn’s prior treaty arrangements the few Indians in the area were friendly.”13

There was no nearby Swedish church at first. For important events like wedding or baptisms they would go by boat down to Gloria Dei Church at Wicaco. Traditionally they met for worship in private houses. About 1730, after Gunnar was dead, the Rev. Samuel Hesselius visited the Swedes of Upper Merion, and held services at the house of Gunnar Rambo.(By then Gunnar’s house was owed by his son Elias.) Hesselius advised the Swedes to build a schoolhouse that could also be used for religious services. The Rambo family donated an acre of land, and a building was completed in 1735.14 A larger stone church was built in 1760.15

Through the 1670s and 1680s Gunnar and Anna added to their family, eventually growing to nine known children. Two of the sons, John and Peter, would serve in the militia in 1704, along with a number of Anna’s Cock relations.16 Since the Quakers strongly opposed bearing arms, even against threats from the Indians, the membership in the militia was strongly Swedish and German.

In 1698 Gunnar’s father Peter died and left 300 acres in West Jersey to Gunnar. The same year Gunnar sold this to John Bowles.17 He had already sold off part of his Shackamaxon land to George Lillington, in 1697, to Thomas Fairman, in 1698, and to John Bowyer, a shipwright, in 1699.18 Gunnar’s land at Upper Merion had been granted for 500 acres. When surveyed, it was found to be 614 acres, but he surrendered the extra 114 acres, and in 1710 he sold 100 acres of his 500 to Hugh Williams. In 1721 he gave his son Gabriel 150 acres, and the remaining 250 acres were granted in his will to his son Elias.19

At first the settlers would have traveled down to Philadelphia and Wicaco by boat, since there were no roads. A few years after the settlement, they forged a road. “It was not an improved highway, laid out by practical engineers, … but merely an improvised cart-track through the woods, replete with turn-outs, and with all the pitfalls and windfalls known to wood-men. Even thus, it was accounted a convenience, for it opened the way to the lime region of the Chester valley, gave ingress and egress to Griffith’s mill, at the Gulph, and provided the ‘back inhabitants’ (as the residents of Upper Merion were called by their more fortunate neighbors) with a road to Roberts mill, on Mill creek, to Merion Meeting-house and to the Philadelphia markets.”20 Access to a grist mill was essential for farmers, and the mill built about 1690 by Edward Griffith on Gulph Creek would have been a benefit to them.21

Gunnar wrote his will in January 1723/24 (1724 by modern-style dates). His wife Anna had died before him, as she is not named in it.22 He named his six surviving sons. He did not name his daughter Brigitta, although she was still living. He must have already provided for her at the time of her marriage to Matthias Holstein in 1705.23 He did leave 5s to her daughter Katherine, the oldest of Brigitta’s six children living at that time. For his sons he left 5s to John, a bed and bolster to Peter, 5s to Mounce, 5s to Gabriel, £40 to Andrew (to be paid by Elias in installments), and the farm to Elias.

He died before March of that year, when his will was probated and the inventory taken. The inventory of Gunnar’s estate, taken on April 10 1724, is startling in its brevity. Gunnar and Anna were relatively prosperous by the standards of the time, yet their goods amounted to two beds, three tables and two chests, with bedding, three cooking pans and pots, a Bible and some other books, a few pictures in frames, six cows, four yearlings and a steer, a grindstone, a pair of plow irons and an old cart.24 There were probably other sundries that the inventory takers did not bother to list, but this is still very sparse.

Gunnar is undoubtedly buried with Anna. They were supposedly buried at Old Swedes Christ Church, Bridgeport, but it did not exist until after their deaths.25 Perhaps the Rambo family had a place for burials on their farm that was incorporated into the land sold for the school and churchyard.

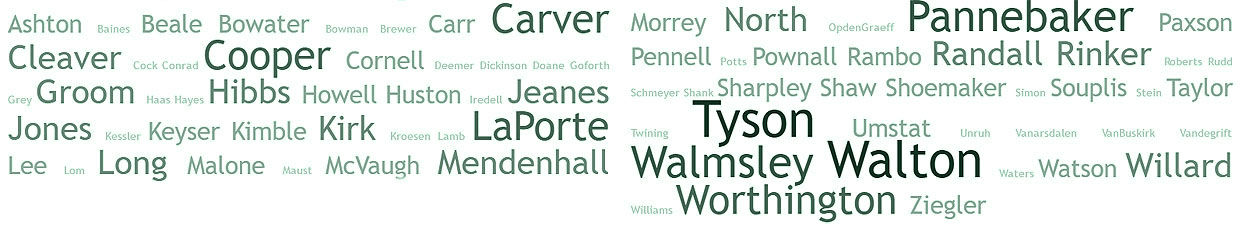

Children of Gunnar and Anna:

John, b. about 1673, d. late 1745 to early 1746, m. Anna Laicon, m. 2) Sarah. Sarah’s last name is unknown.26 Lived in Upper Merion on a tract of 350 acres. Served in the militia in 1704. Had seven children with Anna before her death, and four more with Sarah. In his will, he named his children and divided his land.27 Children: Peter, Måns, Gabriel, Michael, Ann, Eleanor, Ezekiel, Gunnar, Magdalena, Lydia, Israel.

Peter, b. 1678, d. 1753, m. Magdalena –; her last name is unknown.28 Lived on Perkiomen Creek, warden of St. James Church in Perkiomen, had six children.29 Magdalena must have died before he wrote his will in August 1744, as she was not named in it. Peter was living with his son John. He left most of his estate to John, in return for “meat, drink, apparel, lodging, and washing suitable to my age and condition”. He left another tract to his son Peter, who was to pay the cash legacies to the younger sons William and Gunnar. The married daughters Ann and Mary each got a shilling, “on consideration of what I have already given her and other reasons best known to myself”.30 Children: Ann, Mary, John, Peter, William, Gunnar.

Gunnar, b. 1680, did not marry, died before 1724, not in his father’s will. He was alive in 1717 when he cut eleven logs for a new parsonage at Passyunk.31

Anders. b. 1682, d. 1755, did not marry, lived on the homestead with Elias, named Elias’ children in his will, written and proved in 1755.32 Elias’ sons Peter and George were the executors.

Måns, b. 1684, d. 1760, m. 1715 Catharine Boon, daughter of Sven and Brigitta. He bought land in Plymouth Township and later moved to Kingsessing. He wrote his will in April 1760, a month before he died.33 He left his Kingsessing plantation to his son Swan, but Catherine, a daughter Mary and two Campbell granddaughters were to have the privilege of living there. His daughter Brigitta had married William Campbell and died in 1758. He left £20 to his daughter Ann, wife of Jacob Lincoln, and another £20 to her son Abraham.34 Catherine died in 1761. In her will she left land inherited from her father to her daughter Mary, and the rest of her property to be shared between Swan, Mary and the two granddaughters. Children: Britta, Ann, Swan, Maria. Neither Swan and Mary is known to have married.35

Brigitta, b. 1685, m. Matthias Holstein, he served in the Assembly for five terms, lived in a stone house in Upper Merion. Church services were held in their stone barn while Christ Church was being built.36 Matthias owned over 1,000 acres in Upper Merion, including Swede’s Ford, an important crossing over the Schuylkill. Matthias wrote his will in 1736, named his wife Brigitta and eight surviving children.37 Children: Catherine, Debora, Andrew, Matthias, Maria, Britta, John, Elizabeth, Frederick.38

Gabriel, b. 1687, m. Christian about 1715, inherited 150 acres of his father’s land with river footage. He died in 1734, and left no will. His wife Christian survived him and administered his estate.39 Children: Matthias, Christina, Martha, Gabriel, Andrew.

Matthias, b. 1690, d. before 1724, not named in his father’s will.

Elias, b. 1693, d. 1750, m. Maria Van Culen40, lived on his father’s plantation on the Schuylkill, owned a ford across the Schuylkill called Lower Swedes Ford. In a road petition about 1746, his neighbors stated that, “Elias Rambo hath built a boat which is of very great Service when the river Schuylkill is High, in helping the Neighbors over said river.”41 He died in 1750; Maria had died before him. He named his eight children in his will, written in September 1748.42 His sons Peter and George were to divide the plantation. Children: Peter, George, Elias, Anna, Andrew, Jonas, Jeremiah, Gunnar.

- By Old Style dating, using in Pennsylvania until 1752, he was born in 1648. In modern dates, with the year starting in January instead of March, it was 1649. ↩

- The primary source for the lives of Gunnar and Anna and their children is the massive family tree compiled by Beverly Rambo, and supplemented by Ron Beatty, here called Rambo Family Tree. The several sections are available in published form and as downloads at https://sites.google.com/site/rambofamilytree/Home (as of 2/6/18). The page numbers given here are for Volume 2 of the tree. According to the Rambo Family Tree, p. 23, they lived on land from Anna’s father Peter. However Peter did not die until January 1689. Perhaps he divided the tract among his children before his death. The entry in Craig Horle, Lawmaking and Legislators said they lived in Shackamaxon for twenty years, selling their land there in 1697, which suggested that they moved there in about 1677. ↩

- There does not seem to be a historical record of such a treaty, in spite of its fame. Records of Penn’s activities in the first few months in the colony are scanty. ↩

- Mary Maples Dunn and Richard S. Dunn, Papers of William Penn, Vol. 2, pp. 337-39. ↩

- Council held 7th 12th mo 1683, in the Colonial Records of Pennsylvania: Minutes of the Provincial Council, 1851. ↩

- Craig Horle, Lawmaking and Legislators in PA, vol. 1. ↩

- John R. Young, Memorial History of Philadelphia, 1895. ↩

- Upland Court Records, November 1677. ↩

- Minutes of the Board of Property, Minute Book E, 4th mo 1691. ↩

- 1693 tax list of Philadelphia County and City, available online. ↩

- E. Gordon Alderfer, The Montgomery County Story, 1951. ↩

- Theodore Bean, History of Montgomery County, 1884, chapter on Upper Merion. ↩

- Gibbons, Edward J. “Matsunk or Swedes’ Land.” Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, vol. 21 (Norristown, PA: Fall 1977): pp. 41-72, quoted in Rambo Family Tree. ↩

- Bean, History of Montgomery County. ↩

- History of Christ Church (Old Swedes), Upper Merion, 1760-1960. ↩

- Jane Gray Buchanan, Peter Stebbins Craig, and Jeffrey L. Scheib, “Captain John Finney’s Company of Philadelphia Militia, 1704”, PA Genealogical Magazine, 1987, vol. 35, p. 165. ↩

- Gloucester County Deeds, Documents relating to the Colonial History of the State of NJ, p. 671. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 23. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 23. ↩

- Charles R. Barker, “Glimpses of Lower Merion History”, online at www.lowermerionhistory.org/texts/barker.html, accessed 2/10/18. ↩

- Charles R. Barker, “Gulph Mill”, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol.53(2), 1929, online at journals.psu.ed. ↩

- A Findagrave entry for Old Swedes Christ Church, Bridgeport, says that she died in 1693. Without a gravestone, it is not clear where this date came from. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 59. ↩

- Philadelphia County estate papers, City Hall, Philadelphia, Estate D.388. ↩

- Findagrave for Old Swedes Christ Church, Bridgeport. ↩

- Since she gave one of her sons the uncommon name of Israel, she may be a descendant of Israel Helm, a soldier and magistrate on the Upland Court. ↩

- ↩

- Magdalena Bauer mentioned her god-daughter Anna Rambo in her will, and this has been misinterpreted as granddaughter, starting with the Publications of the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, vol. 5. However the journal of Henry Muhlenberg, her pastor, described her as a “maiden lady of New Providence”, who was living at the time of her death with a good Reformed man and his Lutheran wife (Peter Rambo, son of Peter, and his wife Mary). (Rambo Family Tree, pp. 51-52) ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 48. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 49-51. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 54. ↩

- Philadelphia County Wills, K.359. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, pp. 56-57. ↩

- Jacob Lincoln’s father Abraham was a brother to Mordecai Lincoln of Chester County, the great-great grandfather of the president. The brothers Abraham and Mordecai were in the iron foundry business together. (Rambo Family Tree, vol. 2, p. 138). ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 56. ↩

- Rambo Family Tree, p. 59. ↩

- Philadelphia County Wills, F.36, quoted in Rambo Family Tree, p. 61-62. ↩

- When did John die? He was apparently not named in the will, but Rambo Family Tree gives his death as about 1755. ↩

- Her last name is unknown. ↩

- Maria was the daughter of George Van Culen and Margaret Morton, and the granddaughter of the John and Annake Vanculin who had testified at the witchcraft trial of Margaret Mattson in January 1683. (Peter S. Craig, “Johan Grelsson and his Archer, Urian and Culin Descendants”, Swedish Colonial News, 2001, Vol. 2(5), online at: http://colonialswedes.net/Images/Publications/SCNewsF01.pdf (accessed 2/9/2018). ↩

- Charles Barker, “Historical gleanings south of Schuylkill, part 3”, in the Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1945, vol. 5(1). ↩

- Philadelphia County Wills J. 305, quoted in Rambo Family Tree, p. 64. ↩

I am a descendent of Peter Gunnarson Rambo and Brita Mattsdotter- also Gunnar and Anna and their son Peter. Please make a correction about Peter’s wife. Peter Stebbins Craig and other noted Swedish historian have shown that Peter’s wife was not Magdelena. She is unknown. You can verify this information at http://www.colonialswedes.net. It is very important to stop the spread of inaccuracies in family histories.

Thanks for the documentation! Ronald S. BEATTY and Cynthia Forde-BEATTY, genealogists for the Swedish Colonial Society

You are welcome. Thank you for all of the research that you and Ronald have done on the early Swedish families.